- Home

- Brian Hodge

Picking the Bones Page 12

Picking the Bones Read online

Page 12

"You must have been upstairs at some point," she said.

"This is ancient history," I told her. "It's been years since what happened here has meant anything to me."

"Years and meaning have nothing to do with each other." Blue eyes and total conviction. "Besides, how can you say that if you don't even know what really did happen?"

"Oh, and you do?" I challenged, but she didn't answer, just moved to the stairs and ascended, one hand on the dingy banister and brushing my shoulder with the other as she glided past.

I rose to follow.

You know where we went.

"It happened right here," she said, this stranger I'd loved—hadn't I? She was pointing to a spot along the floor, a few feet from one set of windows. "The bed was here, and he sat on the floor and this is where he slid the needle in his vein. A few seconds later he tried to stand but he fell back on the bed and never got up again. He died staring at the ceiling. But what he was looking at, who knows?"

"So what. So fucking what. You're an obsessive fan who somehow managed to hide it until now. You're the one who needs to come to terms." Telling her this, but thinking now that it was never me she'd loved, it was him all along—the image of him, the stupid fantasy of him, because she'd been three years old when he died, and I was just the consolation prize.

She ignored me, moving now to the other wall's windows. "But he'd looked at enough for one night."

Gaze out these particular windows and you had an excellent overview of the farmhouse's backyard, long since overgrown and wild, but once it must've been open and mown, a green sea, and the flagstones to the barn like a curving archipelago.

"He watched it happening from here," Sonja said. "She thought he was asleep and so he wasn't supposed to see it, but he did, and that must've been why he killed himself. But he didn't do it right away, because she was finished already and he was still alive, so he probably wanted to make sure he wasn't hallucinating. He killed himself in front of her, you know—he didn't die alone."

"You can't know these things," I whispered.

She merely smiled. You can argue with anything but a smile.

"Watched what happening…?" I asked, crumbling the way she knew I would.

"Do I have to say? It can be enough of an insult to tell a man what his mother did with other men…let alone something very tall that walked out of the woods late at night, that she was waiting for…because unlike so many, she always knew who and what she was."

And I suppose it was right about now that my head began to pound—

"She was such a tall woman, do you even remember that about her?" Sonja said. "You can't really tell so from any of the pictures you showed me, but she was uncommonly tall. Maybe why you don't remember is because all little children think their parents are tall. But where do you think you got your height?"

—and I felt that I was about to scream, because I wasn't supposed to care.

"Do you even remember her name?"

And I stammered out that it was Gudrid, something like that, a name I'd never even thought was real, because it sounded like one of those fantasy names that counterculture airheads were fond of using back then. But no, Sonja said, it was my mother's real name.

"I should know—it's Icelandic," she said. "They've told your uncle about what happened in Iceland by now, haven't they?"

Sonja stood before me with her cold beauty and her hair like the sun shimmering on ice, so much more in control of herself than I was as I pleaded to know who she really was, where she had really come from, who had really sent her to meet me so many years ago, if it had to do with these people at Miskatonic who had drawn Terrance in. But her inarguable smile was sad in its refusal, and all she would say was that there was science, and there was worship, and sometimes, if very rarely, they overlapped.

"I could worship you, too," she said, "if it wasn't for your ignorance."

But why would she ever want to, I wondered, but didn't want to know, either because of what it would say about her or imply about me.

"So I'll settle for this…"

And I swear it was Sonja who picked up the discarded bottle, heavy old thing long drained of wine, and put it in my hands, then knelt before me and tossed her head back and looked up at me with the kind of expectation you might expect in the transcendent eyes of sacrifices who willingly laid themselves beneath the obsidian knives of Aztec priests. Giving themselves to a higher cause.

"If it helps you to know, to awaken, then do it…"

And here I was, years later, back with the sick mindfuck games all over again. No different than with the unhealthy women I swore I never wanted to meet again, who'd wanted me to cut them, to whip them, who weren't happy unless they were hurting—did they smell something on me?

"Do it!" she shouted, beautiful Sonja whom I'd never known, who'd come to me for reasons I'd never suspected. "Do it…or I'll tell you about your real father."

That did it.

It's astonishing how sturdy thick glass can be, how hard and how many times it can hit something before breaking.

It looked far too timeworn for Sonja to have brought it here over the past days. Whoever had left it, years ago, decades even, I wondered what dim impulse they'd obeyed; if they’d had the faintest sense the bottle was meant to be left here for just this day.

To kill the future daughter-in-law of their fallen god.

*

For the trip home, I ignored the airlines and took Sonja's car, in part because I didn't want to leave it behind to be found. To possibly be linked with the remains of the unidentified woman sure to be discovered sooner or later. Most of her I left in the cleansing waters of the woodland brook near the farmhouse. The rest, which might have established her identity from fingerprints or dental records, went elsewhere, many elsewheres, for more thorough concealing.

I found it amazing, the survival instincts that welled up within me. I did these things as if the self I'd always known was watching them be done by another self who had assumed command. Another self I'd never realized was there, buried deep in bone and DNA.

And afterward, there was Sonja's car and rolling solitude across a continent's worth of roads. I felt so numb that I had hardly any sense of seeing the eastern third of the country, able only to drive and sleep and, just barely, eat. I would drive late into the night and the frosty black breath of its autumn chill, and sometimes I would stop on a desolate stretch of highway and stand beneath the frozen light of stars, listening for their music.

On the third night I was finally able to sit awake with myself and my deeds in the cheerless box of a motel room. Nebraska, this was in. On the bed, I opened the lid of the wooden box containing what little I had to remember my earliest years by. I'd packed it for the flight to Vermont without really knowing why, only that it seemed fitting, full-circle.

Inside were the worthless, priceless treasures of a young boy. Trading cards, seashells, those few faded family photos. Guitar picks. A little pistol that must've belonged to a toy soldier, long lost. Two Matchbox cars. A bone, small but strangely dense, from nothing I could guess. A magnet. Stuff like that. I held it all, piece by piece, and marveled at how small our worlds are when we're young.

At the bottom lay a brown envelope, a tiny thing really, two inches by four. Small as it was, it had been rubber-stamped with the name and office address of a dentist; the town, I was surprised to see, was just a few miles from the farmhouse. Penciled notations, too, in what might've been my mother's hand—my first name, and an October date only two days before my father had died. I had to smile at this unexpected evidence of maternal responsibility, my mother taking me in for a checkup.

I opened the envelope, probably unopened since I was ten, and slid out the only thing inside: a pair of dental x-rays, ghostly blue-white on black. When I held them up to the light of the motel lamp, they were clearly a child's, the baby teeth grown in, the adult teeth in their hidden sockets above, waiting their turn.

But above those, there

were more.

Along each side, high in the bone of the upper jaw, deep in the bone of the lower, they abided even then: wide teeth down the center of each side, long and razored, that looked made to mesh together top and bottom like meat shears.

Whether they had implications for a future still to come, or were vestigial leftovers from aeons ago, I couldn't begin to guess.

But no wonder they were in with the family photos.

6

So I returned to my home in the mountains, and to the one thing that had always helped me find purpose: my work with the sounds of other worlds, of other people's dreams and nightmares.

I had a film to finish up, and came through for the studio and its deadlines, and the day after the package of my sound design arrived down in Los Angeles, to be layered into Subterrain's soundtrack, I got a call from Graham Pennick, who had no reservations in proclaiming it the single most unsettling work he'd ever heard me, or anyone, do. Parts of it really got under his skin, he said, although he couldn't say precisely why, and of course asked what I'd done, what my sources were.

"A little of this, a little of that," I said, elusive. "From here and there."

Which he respected, of course. Trade secrets. There was no need to mention how far away some of it had come from in time and space.

And it was around then that Uncle Terrance lost the power of speech, so we communicated by e-mail for a short while, but by now there was little more to share than his misery.

This thing growing inside is eating me alive, he wrote in the final missive I received from him. If it's true we were made by conscious design, we still were not made in benevolence. There can be nothing crueler than an evolving world.

I believe you have a point, I wrote in reply. Just look at the teeth that rise to the challenge.

But I don't know if he received this, because the next thing I heard—from his companion Liz—he was dead. He'd been squirreling away painkillers until he had enough of a cache that would rob the cancer of its last laughs. The unspoken implication was that she'd helped him make his exit. For which I thanked her.

But while I know she made him happy, I had to wonder if Liz was really who he thought she was. Or if she was with him according to dictates other than those of her own heart. You'll naturally understand my paranoia, since I have to wonder when all this really started. If my Aunt Genevieve's murder truly was an unsolved mugging, or only looked like one. The surest way of shaking up Terrance's life, getting him to Norway and the skull, which then made its way to me. The surest way of bringing in Liz to ease the fresh loneliness of his life…and make sure certain things got done.

I have to wonder if his colleagues at Miskatonic were players, or mere pawns on a much grander scale of dominion. Because, as Sonja had said, there is science, and there is worship, and sometimes they overlap.

Or maybe it all began earlier still, with my birth, or my father's death and my abandonment, so that someday I could more easily receive this legacy of chant and bone. Marked for this, perhaps, even while in Gudrid's strange womb, then once I was free, imperceptibly guided the rest of the way.

Years ago it occurred to me that when you can barely remember your parents, you can hardly know who and what you are.

And now, while I still agree with this, it occurs to me that discovering such knowledge, rather than growing up with it, means it's much less likely to be taken for granted. Or rebelled against.

I think of another conversation Terrance and I had while he was here, the day after he'd given me the skull. I was intrigued by those huge intervals in the geological levels at which the various specimens of homo sapiens primoris had been found. It wasn't a smooth, continuous fossil record. Instead, they'd been found in four distinct strata—from roughly thirty million years ago, eighteen million, six million, and, like the skull he gave me, just 350,000. Mostly consistent in form, but separated by vast gulfs of time.

"What do they make of that at Miskatonic?" I'd asked.

"The natural inference is that something periodically seeded the earth with these beings," Terrance had said. "And long after they went extinct, tried again…until maybe, finally, they flourished."

"Are they us?" Something I would not bother to ask now. "Are they any part of us?"

"I'm not even sure what 'us' means anymore," he'd said. And wouldn't look at me. "But if we really were created in some other being's image, I'm no longer sure I like the prospect of who or what that might've been."

*

Periodically, news will come to me that I'm much better equipped to know what to make of now, how to read between its lines, than I would've been before receiving my birthright.

When I first heard about a tiny town in Iceland that had been mysteriously burned to the ground, every last inhabitant slaughtered, I immediately knew what to make of it. And understood instinctively that the world is poised to embark upon another cruel path.

When similar events occurred in Canada and Germany and Brazil, I saw the same hand at work, and didn't need the affirmation furnished by the large footprints left behind.

But news comes from much closer to home, as well.

The soundtracks of major films are generally mixed by three audio engineers working at a large board. When word got back to me of the strife between the trio who mixed Subterrain, and how they twice had to be replaced, I thought back on my late-night experiment that had caused coyotes to tear one another to pieces.

When a couple of weeks later I learned about the arrest of two of the studio executives who'd sat in on the screening of a preliminary cut of the finished film, I understood why they might've gone on their killing spree afterwards.

The pre-release buzz is that it's an extremely powerful movie.

A major holiday release, it premiers nationwide in another week, in more than two thousand theaters. I look forward to opening day with great anticipation.

Once I wanted to burn the earth—remember? Never dreaming I would be handed the chance, in the service of ancient gods whose names I don't yet know, but whose titan souls I suspect I've always heard.

I began by telling you that I'm more my father's son than my uncle's nephew, and surely this is more true now than I ever fathomed it could be, if Sonja's final words really were spoken from knowledge:

Do it…or I'll tell you about your real father.

But until he makes himself known to me, I will above all regard myself as the son of my mother, and yearn to see her one more time…

If only to show her how I've grown.

BRUSHED IN BLACKEST SILENCE

From the way the house was described in the letter two weeks earlier, he’s been expecting it to scowl and grimace. Instead, from the road at least, it hardly seems worth a second glance.

I am coming to fear that it may be an accursed place, the Baron wrote, harboring malice toward those who would exercise even the smallest right of mastery over the property. Yet I am determined to make the most of my investment in it, and the artifacts upon its walls.

As the carriage clatters nearer, the driver pulling back on his reins, Abraham’s first judgment is that the Baron may have a keen imagination for a banker.

It’s a country house, no more and no less distinguished than a hundred others he’s seen. It stands two stories of brick and adobe, little adorned but for the tall, narrow windows, its garden and grounds nourished by the same stream that feeds a marble fountain, ill maintained of late and green with algae. Close by, a stone well juts from the ground. Farther away, the green tendrils of a small vineyard twine about their arbors.

La Quinta del Sordo, the place has been called for generations. The House of the Deaf Man.

A cluster of white poplars throws some precious shade near the house, an oasis from which the Baron waves and beckons. He looks reluctant to leave it, and Abraham can sympathize. Spain is an arid land. He feels cooked here, its sun a savage cousin to the sun of the north.

Thanking the driver, he steps from the carriage, then ta

kes a moment to stare at the house; imagines that it stares back and then imagines what it might see in him…an enemy to repel, an ally to win over. The driver turns back for the dusty road to the east and the sprawl of Madrid, a proud sea of steeples and red tiled roofs beyond the gentle curve of the Manzanares River. Yesterday Abraham was told at the Museo del Prado that the painter Goya, when he lived here, enjoyed watching the city’s washerwomen come down to the river’s edge.

He joins the Baron under the poplars. They’ve done their catching up already, the way old family friends should, over beef and cognac and cigars three nights ago, after Abraham first arrived in Madrid. He learned then that the Baron was a father of four now, rather than three. Sons, all of them. He’s seen none of them, nor the Baroness Mathilde since the wedding nine years earlier. And to Abraham, their titles means little. Ties between the Van Helsings and the d’Erlangers reach back three generations, to the years before Belgium took her independence from the Netherlands. For all he knows—because he would rather read books of words than numbers—Frederic and his family might still be watching over some of the old Van Helsing investments.

The years between them are beginning to seem wider. Frederic is a dozen years the younger, not yet forty, and seems to have adapted to the dryness and dust of Spain with ease. He’s abandoned the frippery of Brussels for a simple linen shirt, dull white in defense against the sun, and the broad-brimmed hat of a country don.

“Two and a half days at the Prado,” Frederic says. “Not long, I realize, but…do you know Goya now?”

Abraham gives a sharp laugh. “Can anyone know Goya? I knew him little before, and not so much better even now.”

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

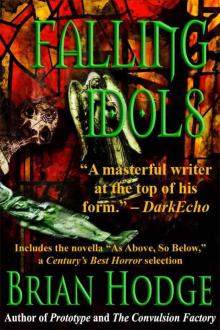

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols