- Home

- Brian Hodge

Oasis Page 13

Oasis Read online

Page 13

When he taped up a poster of the famous shot of Albert Einstein sticking out his tongue, I was about ready to give up on Greg. But then he took a break and produced, of all things, a water pipe. I watched in amazement as he loaded the bowl and lit it and sucked it into life. My pudgy little computer whiz had turned out to have a genuine vice after all. And I guess it redeemed him with me. This, and the fact that he soon pulled from a gym bag a fresh box of crunch donuts. Finally I was in the presence of another human being, whose taste in donuts was impeccable.

Maybe Andrews hadn’t been such a bad idea after all. Maybe it really was the first step down a new and better road.

But, as it turned out, I was just being naive.

Saturday evening.

Phil’s room, down on the second floor, put my own conventional room to serious shame. Previous occupants had remodeled it in some unknown year. Bunk beds had been installed, leaving floor space for a love seat and a small rented refrigerator and a bookcase that supported Ashley Hopkins’s terrarium, complete with hermit crabs. There was also a stereo and a small color TV, neither of which were Phil’s, and plenty of posters and pictures adorned the walls. Along the bedframe ran a bumper sticker that read No Virgins Here … Andrews College Screws All.

I took it all in for several moments, cloaked in increasing humility over my own boring room. “Damn you, Phil. This is a penthouse.”

Phil grinned modestly. “I call it home.” He gestured toward the love seat, where I plopped down, and he leaned onto his bed, the lower bunk.

I grinned wickedly. “What’s he like? Ashley. Is he a fruit?”

“Hardly.” Phil shook his head. “So far, the guy’s had a date every night. Never with the same girl twice. I don’t know how he does it. This isn’t even a coed dorm. He must spend hours hanging around outside the girls’ hall next door.” He laughed and shook his head ruefully. “Just my luck. I finally get a girlfriend at home, and now I live with the campus stud.” Phil paused long enough to pull off his big shoes. “But he’s not a bad guy, and not an asshole about his stuff or anything. He’s a psych major from Chicago. Your mom’d love him. Except he keeps hassling me about coming from a farm.”

“Up there, they think anything past the South Side is the sticks.”

I toyed with the hermit crabs and Phil sat watching, mesmerized. As if his mind were light-years away.

“Do you miss it?” I asked.

“Miss what?”

“You know. Home.”

Phil turned onto his back, hands behind his head and knees drawn up and aimed at the bunk above. “In a way. Not much, though, because I like it up here. Well, Connie I miss a lot, but everything else is just little things. Know what I mean?”

Little things — that made sense. Dad’s cracking ankles came to mind. Family cookouts. The way Mom seemed to have saved every piece of aluminum foil she’d ever used. The little things.

I shook my head. “I gotta tell you, Phil, you’ve adjusted to it a lot better than I have. I’ve felt like shit about it for all but fifteen minutes here and there. And you’re the one with the blond, fair-skinned goddess at home.”

“Yeah, not having her around is the biggest drawback.” Phil had been looking happy, optimistic, all those good things I wished for him. But as he moved around on his bunk and stared up toward the ceiling, all that drained away. “The only drawback, really.”

His eyes flicked down to mine, and he caught the puzzled concern in them. I knew things had taken a sudden turn for the serious.

“What’s going on, Phil?”

He sat up, hunched forward with his hands clasped together as he stared into the floor. “We’ve always been pretty open with each other, never held back. But … there’s something I’ve never told another soul. Least of all you and … and Rick. I guess I was just ashamed of it.”

I let him sit quietly for several moments.

Phil swallowed thickly, his Adam’s apple bobbing. “Ever since I can remember, my dad liked to beat on me.”

The words were sharper than a slap in my face, and infinitely uglier. A big part of me inside sunk. Just sunk, down into a sickening swell of sorrow at what he must have endured over the years. The sorrow where anything you try to say comes out sounding trivial to your ears. There was guilt too, at not having figured this out from little cues he’d probably dropped, unconscious pleas for help. Oh, such a friend I’d been, yes. I felt suddenly dirty.

“It was the same way with my sister. That’s the main reason why she got married when she was seventeen, back when you and I were in seventh grade. I guess she’s been one of the lucky ones, because it’s worked out for them and they’ve got a good thing going, but mostly it was a way to get out of the house.” Phil paused a moment, kneading his hands. “You know that scar on my back?”

I nodded miserably. I’d first noticed it while swimming several summers ago, a long, narrow, knotty ridge across the small of his back. When Rick and I asked about it, he told us he’d gotten it once at his grandfather’s, trying to crawl under a barbed-wire fence.

“Dad gave that to me one day when I was in second grade. Caught me playing with matches and lighter fluid. He whipped me with a switch cut from a tree. Just pulled off my shirt and kept hitting me in the same damn spot, over and over.” Phil laughed nervously, and I think he did so because if he hadn’t, he might’ve cried. “The worst of it was that I had to go to the tree and cut the switch off myself.”

I balanced my head on one hand, bent forward like a drunk getting ready to heave. “Why didn’t you ever tell us before? I guarantee you my parents would’ve taken you in. Or Rick’s.”

“I guess I just figured I had to handle it on my own. And I had my sister to talk to. And by the time I even thought of anything like that, I didn’t want to desert my mom. He never laid a hand on her, just my sister and me, but I still didn’t want to abandon her back then.” Phil shrugged, then pointed to his back. “Don’t think it was always as bad as that. Mostly he’d just smack me with his belt, or punch me in the ribs or stomach. He didn’t leave marks many times. Maybe he got scared after all the child abuse stuff hit the fan.” Phil paused. “Don’t get me wrong. I’m not sticking up for him.”

I shook my head.

“Anyway. Now you know.” He looked me in the eye for the first time since he’d started. “You envy me the way I’ve adjusted to being up here? I’ve always envied your home life. It always seemed so stable, like a rock. It was always there for you.”

He was right, of course. I’d never really looked at it from that perspective, for it was something I could always take for granted. But sometimes it takes a slap in the face to realize how lucky you’ve been.

“I don’t know what to say, Phil,” I told him softly.

He smiled warmly at me. Stoically. “No need. It’s all behind me now. I’ll make sure of that. Somehow, I’ll make sure.”

And I believed him.

Funny, the way we’d both ended up here out of similar motives. We each had drastically different reasons, but it all boiled down to the same thing: trying to escape something that was awfully hard to let go of.

But at least we were trying.

Chapter 23

First impressions can be deceiving, but after the first couple of days, I decided I was going to like my classes. Perhaps it was only because I am my mother’s son, but my psych course showed the most promise, and the professor had a great sense of humor. My business course looked to be my least favorite. Even so, I liked the professor, though it may as easily have been pity. He was tall and pale and pasty-faced, and if he hadn’t been as animated as the scarecrow from The Wizard of Oz, he could’ve been described as cadaverous. The kicker was his unlikely last name: Dedman.

Early Tuesday evening, I eased back on my unmade bed to read the first couple chapters in the text for my life sciences class. M*A*S*H, that perennial syndication champion, had just finished on Greg’s TV, the picture fading to a pinpoint of light in the center of t

he screen.

Things had been going as smooth as silk so far. I’d found all my classes easily, I was meeting a few people with nary a flaming asshole in the lot, and the work hadn’t been piled on with a shovel yet. Smooooth.

Until my mom called a few minutes later to tell me that Dad had just had a heart attack.

I made the four-hour trip home in just over three, reaching the hospital by ten-thirty. I entered the lobby, and the matronly woman at the desk informed me that Dad had been taken upstairs to the intensive care floor. I jogged to the elevator bank, legs shaky and feeling about as substantial as lukewarm water.

Mom and Aaron sat alone in a fourth-floor alcove, Mom looking composed with her hands folded in her lap. Aaron still wore his Chuck Wagon uniform and his hair was in tangled disarray; he sat in a bleary-eyed slump that reeked of exhaustion.

Mom jumped up to hug me. I hoped she wouldn’t start crying, having to rehash everything that had happened so far, and she didn’t. Strong lady. I’d always admired that.

“Thank you, Chris,” Mom said, clutching me by the shoulders. “I know it must’ve been a hard drive after all day at school.”

“Never mind that,” I said. “How’s Dad?”

“He’s doing as well as can be expected.” Mom motioned us to sit down. Aaron and I flanked either side of her. She reached out to take each of us by the hand, but directed her comments to me. “They can’t make any predictions this soon. It’s always the first seventy-two hours that are the crucial ones. But so far, so good, hon. They’re giving him a drug to dissolve the blood clot that caused this.”

Mom released our hands and leaned back in her chair, closing her eyes. Every moment of this agonizing night was written in longhand on her face. It made her look older. Then her eyes opened, wearily sought mine.

“Chris, I tell you, I don’t think I’ve ever been as scared as I was when that happened tonight. We were clearing off the supper table and he—” Mom squeezed her eyes shut for a moment. ”He dropped a plate. It sounded like a bomb. He was standing there looking out the window. And then he just fell back into his chair. And the look on his face was the most awful thing I’ve ever seen. Like he was sick to his stomach and surprised and scared to death” — she wrinkled her nose at this choice of words — ”all at the same time. I hope I never see him like that again for as long as I live.”

I patted her hand. “What room is he in?”

“Four-eighteen.” Mom pointed down the hallway. “About halfway past the nurse station.”

“Can I see him for a minute? You know, alone?”

“Hon, he’ll be asleep right now. And he doesn’t look very good.”

“That’s okay, that doesn’t matter. I just want to see him.”

“You better ask the nurse first.”

I got up and headed for the station, silent on the carpeted floor. Two nurses were seated at the desk, the younger of the pair closer to me. When I stepped before her, she looked up from some paperwork with big brown eyes that any patient would find comforting.

“My father’s down the hall. Anderson.” I cocked my head in the direction of his room. “I’d like to see him if I could.”

“Okay. Just for a minute. No more.” She came out from behind her desk and I followed her brisk, noiseless stride to 418. She almost seemed to float above the floor. The door had been pulled to, but not latched. She eased it open, light spilling in in an ever-widening arc, illuminating Dad little by little as he lay on his back, hands balled into limp fists on his stomach.

I gently walked in, remembering the night we’d chopped wood together less than a week ago, how he’d been clutching his shoulder by the time we were through. Early warning sign? Probably. And now, his only movement was the slow, shallow rise and fall of his chest and stomach.

Mom was right. He didn’t look good.

He had more things plugged into him than an overloaded outlet: IV, oxygen, cardiac monitor, who knew what else. He was sweating too, beads standing out across his face and forehead. And as I peered closer in the dim light, I could see something around his lips, caked into the corners of his mouth. It looked like dried blood.

I reached out to touch his hand as it rested on his stomach. It felt warm and dry. Warm. The little hairs bristled under my fingers. Dad didn’t stir, but that didn’t matter. The simple warmth of his hand beneath mine was the greatest sensation I could hope for.

I turned and joined the nurse as she waited in the doorway. “Thanks. But why does he have blood around his mouth?”

She pulled the door to again before answering. “If the situation’s right, we administer a drug called streptokinase. It dissolves the blood clot lodged in the heart. It’s got side effects, though. Heavy perspiration, I’m sure you noticed that. Bleeding, too. Gums, stomach, injection sites. We give other medication as an antidote, but it doesn’t totally counteract it.”

“But it’s nothing to worry about?”

She smiled reassuringly, no doubt a practiced gesture but it still came off genuine. “Not at all.”

She walked at my side toward her station. “Your dad seems very strong. Most heart-attack victims zonk out and go to sleep a lot earlier than he did. He was with us right up until we snowed him with morphine.”

I felt a weird surge of pride. That’s my dad.

“Want some advice?” she said lightly. “For what it’s worth?”

“What’s that?”

“Go get some sleep. You look worse than he does.”

I chuckled. True, I could feel the day exacting its toll. It was hooking weights around my body, starting with my eyelids. Whatever adrenaline I’d been running on was drying up fast.

“Thanks again,” I said, leaving her to rejoin Mom and Aaron in the alcove. Mom wanted Aaron and me to go on home, and we argued about it, then gave in. Mom said she’d be behind us a few minutes later. Fat chance, I thought. She’d end up sleeping in her chair, legs doubled up and her head at a crazy angle unfit for humans.

Aaron and I spoke in desultory fragments until we made it home and I wheeled up the driveway. Despite the fact that it was completely dark inside, I didn’t think I’d ever seen it look more inviting. I was so looking forward to climbing into that familiar bed in that familiar room, hearing the house creak and pop around me as it had done for years, keeping me company through the night like an intimate friend.

Inside the house, Aaron headed for the bathroom while I hauled my suitcase into my room. I kicked off my shoes, then wandered to the kitchen to pilfer the fridge. Fix a bowl of Wheaties, or find an open soda that needed finishing. I flipped on the light and stopped in my tracks.

But then, I hadn’t really expected Mom to clean up the mess, had I?

Fragments of the papaya-colored plate had skittered like shrapnel from where it had been dropped. Bits of food were stuck to the tile. Another plate sat on the counter beside a pair of glasses. A pan of broccoli, long cold, sat on a stove burner. Salt and pepper, still in the middle of the table. A towel, hanging half in and half out of the sink. And most of all, worst of all, Dad’s chair lying on its back angled away from the table. Nothing else spoke of what had happened quite so eloquently as that chair.

I quickly hurried over to set it back up. Priority one.

I was still picking up shards of the plate when Aaron appeared in the kitchen doorway, wearing shorts and nothing else. His face appeared freshly scrubbed.

“Need any help?” he asked.

I shook my head. “Nah, I can take care of it. Go on to bed.” I cringed as my fingers squished a cold piece of broccoli, which I passionately hated even when warm. I scraped it off on the edge of the plate. Priority two.

“Chris?”

Aaron was still there, watching me with an uncertain, frightened look. “He’ll be all right, won’t he? I mean, they wouldn’t be bullshitting us, would they? He’s gonna be fine?”

“Sure he’s gonna be all right.” It was too early to say, but what else could I believe? I kneed my w

ay over to the trashcan and dumped the pieces of plate, then went for a damp dishcloth to wipe the floor. “What makes you wonder about that?”

“Well…” Aaron stood awkwardly in the doorway, leaning on one shoulder while one foot twisted atop the other. He stared at the floor where I was cleaning. “You always hear how they keep things from you, don’t tell you stuff so you won’t worry. You know how it goes.”

I tossed the dishcloth toward the sink and stayed squatting on the floor. “They’d level with us if it was that bad. It’s not like this is a terminal disease.” I looked him straight in the eye. “He’ll be fine.” Then I forced a grin. “You should’ve seen him when I looked in on him. Just like he was ready to get up any minute and take us both on.” I was lying through my teeth, but some lies are excusable.

“There’s something else, too.” His foot kept grinding away.

“Like what?”

His face scrunched up, as if he were recalling the worst kind of memory. “When Mom called me at work to tell me about it, for just a split-second I felt ... I felt glad! It was for just a second, but it was there, and then I was wondering where it came from, and feeling guilty as hell.” He looked about two steps away from tears. “What the hell’s wrong with me?”

It was probably just a weird reaction from the stress of the situation, which definitely had the power to warp your mind a beat or two. But I couldn’t explain it much beyond that — Sigmund Freud I wasn’t. And I certainly couldn’t point any judgmental fingers at Aaron. I wasn’t much of a role model for the way I’d handled all my stress factors this summer. So I tried to set his mind at ease the best I could.

Finally he smiled, sort of, and stood with both feet on the floor.

“Go to bed, Beave,” I said.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

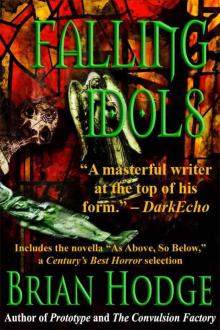

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols