- Home

- Brian Hodge

Deathgrip Page 14

Deathgrip Read online

Page 14

Choruses of amens, more than a little delighted laughter.

Is this guy ever smooth, Paul thought. But is he for real?

He pondered this throughout the rest of the show, whose final quarter was devoted to healing. What he’d been waiting for all along, a fascination of watching wheelchair-bound people stand upright, apparently for the first time in years. Of watching Dawson cup his hand over someone’s eyes, should they suffer from cataracts, and then hearing them count aloud, oh so excitedly, how many fingers Donny was holding up. Of watching Donny know, with no prompting, their names and ailments and addresses and even the names of their doctors.

But was he for real?

Paul watched as the tape broke away to someone giving a tearful testimonial as to how surely Donny Dawson knew Jesus better than anyone else around. And maybe he did, who knew? Paul felt caught in the middle of skepticism over Dawson’s ilk as a whole, all the negative press they had earned over the years, and firsthand knowledge that healing could in fact be genuine. Stranger things in Heaven and earth, et cetera.

Okay. For now, give him the benefit of the doubt.

As lively hymns played under the closing credits, Paul shut off the TV and returned to the sofa. Lying there to wait out the lingering discomforts of head and belly.

While, quite unbeknownst to him, subtle, permanent changes worked themselves within his body.

Dog day afternoon, when August heat clips tempers short and sets them alight like fuses. Registration day at Wayne Johnston Elementary School in West St. Louis County provided a perfect exhibition.

A sublimely typical brick and masonry building, its front walk was lined with a melting pot of angry parents and concerned citizens and that peculiar breed of busybody with more curiosity than brains. Lots of placards and picket signs in this group, along with shouted protests and invectives, a scenario of ironic throwback to war protests recent and distant, Persian Gulf and Vietnam, when they were righteous and full of brotherhood and love of fellow humanity.

Any way the wind blows.

A lone pair — not counting the two uniformed cops flanking them — paced up the front walk, eyes aimed only at the school doors. The woman was Carole Manion, he knew this from the papers, and her son was Chad, eight years old and a veteran of more humiliation than anyone should experience in a lifetime.

Chad Manion, hemophiliac, blood transfusions going back years. And now here he was, like Hester Prynne of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel, condemned to wearing a scarlet A. Hers had been literal, adulteress, and while his was figurative it was no less stigmatic. Chad Manion, the latest AIDS poster child and cause célèbre on a seesaw of skewed values.

The last thing in the world mattering to the populace was that Chad had not developed AIDS Related Complex — not yet, at least — but merely had the virus. Dormant. The word was enough, AIDS, touch of death, and that was all they needed to know.

A long, hot summer had come to a frothy head, lawyers and mediators squaring off, the school board and ACLU in head-to-head combat, all to simply win Chad permission to attend public school again. Rather than sequestering him off in some airless little cubicle away from other children, circa 1920s tubercular care.

Victory had gone to the Manions, but permission meant only that they had the law on their side. No judge on earth could mandate acceptance and understanding and sympathy as a part of the decision.

By the sidewalk near the school doors, beneath a cloudless sky and a flag, stars and bars in flight, Paul watched this solemn processional. The boy was small for his age, with enormous eyes under uneven bangs, and he grasped his mom’s hand and stuck very close to her side.

Mama’s boy, some would jab, but could you blame him? The only person in the world left for him to trust. The paper had catalogued ample family tribulation. Chad’s father hadn’t been around for years, while relatives found excuses to keep their distance, nothing personal. Neighbors and parents of classmates had put on such shows of support as pitching bricks through Carole’s car windshield and slashing its tires, and spray-painting graffiti on their house. And the phone calls, anonymous and ceaseless and brutal, heedless of hour, and despite a switch to an unlisted number, it still somehow got out. According to the paper, Chad often lugged around a male Cabbage Patch Kid named Elliott and called it his best friend, only friend.

Those who claimed that AIDS was God’s wrath upon homosexuality obviously were not seeing the full picture. Nothing like the tunnel vision of the self-righteous, and Paul wished they could all be brought here.

Following the lapse earlier this month, he had never felt better in his life. He was primed. Watching the Manions, he felt the baseball in his hand, idly spun it in his fingers. And eavesdropped on whatever conversations went on around him, more intimate than the tiresome shouting. Those who traded ignorance and superstition and dread back and forth with a dark glee.

“—don’t understand why they don’t just lock him up—”

“—heard he spits at people so he can take as many with him as he can—”

“—and he’s always bleeding out his little hind end—”

A bottomless pit, no limit to the wit and wisdom of these sages. A plethora of paranoia. Only a matter of time, then, before someone directed a comment his way.

“You don’t look old enough to have a kid coming here.” This from some plump fellow, mid-thirtyish and round-faced and peering at Paul through thick glasses. His sanctimonious little lips were pursed in concentration. Mister Priss. “Do you have a brother or sister coming here?”

“No.” Paul glanced up at the picket sign the man carried — DISEASES DON”T HAVE CIVIL RIGHTS — very clever, think of that all by yourself? “I thought I’d come down here for a look at just how far some pea-brained assholes would really carry something.”

Mister Priss nodded, happy to find an ally. “Boy, you got that right. Those Manions are going way too far.”

One beat, two beats, dramatic effect only, but after years on the radio, Paul had it down perfect. One more glance at the sign, then straight-on at this goofy butterball.

“I wasn’t talking about the Manions.”

Mister Priss blinked, sputtered something that kept tripping over his indignantly quivering lips. He shook his head in astonished disgust and, tossing nervous glances back over his shoulder, scurried off for the shelter of kindred souls.

Chad and his mother and their escorts were some twenty feet from the school doors when Paul stepped onto the sidewalk. He was extremely conscious of body language, trying to convey as little threat and as much relaxation as he could. One cop’s hand dropped to his nightstick, at the ready, and Carole Manion braked to a halt, child at her side, and Paul was more afraid of her eyes than any nightstick. Tough, oh man, had she gotten tough, and the cop was warning him aside, polite but no bullshit allowed here.

Chad was scared to death, huge petrified eyes, and Paul wished for a quick close-up, run that sight up the flagpole and see who goes home with his tail between his legs. Shame on you all.

“I don’t want to stop you or anything, I just wanted to wish you good luck.” Paul squatted, closer to Chad’s level. No one can pose much of a menace with elbows on knees. “And I wanted to give you a present.”

The baseball in his hand had been a brainstorm he had gotten after reading that Chad was an enormous Cardinals fan. He’d had KGRM newsman Russell St. James exercise a couple contacts he knew within the Cardinals organization, and obtain a baseball with a very special signature.

Paul held the ball toward Chad, perched in fingertips, the autograph visible. Undecided, Chad glanced up at his mom, what do you think? Though still wary, she had softened considerably, and nodded.

Chad took the baseball. Cupped it in his hands, looked up with amazement. “Wow. Ozzie Smith?”

“You don’t already have one, do you?”

He wiggled his head back and forth. “Nuh uh,” turning the ball over and over, as if to convince himself beyond doubt that

it was real.

The cops didn’t know what to make of it. Carole Manion wasn’t faring much better. And the welcoming committee was looking at Paul as if he were some alien life-form, more loathsomely reptilian than human. He rather liked that look on their faces. For in no way did he wish to be one of them.

He only wished he could pass his hands over the lot of them, and remove all the fear, all the misunderstanding, so Chad could get on with the usual Tom Sawyer/Huck Finn business of growing up in Missouri. But not everything could be changed here today.

Maybe the Manions could move somewhere else, their names and faces unknown, where midnight phone calls would not disturb their sleep. And where total anonymity was a blessing that would make them even with everyone else. It was Chad’s best chance, perhaps his only one, and this they would have to figure out for themselves.

“That baseball will cost you a hug.” Paul nodded as if he could never take no for an answer. “You look like maybe you could use one.”

Chad, ever so tentatively, nodded too.

So Paul collected his due, letting it linger a good long moment. Because he wanted to make extra sure about this one.

Chapter 12

Birthdays can bring out the sadist in anyone, and standard KGRM policy was to show no mercy. On Monday, the twenty-sixth of August, receptionist Sherry Thomason achieved the two-decade mark and proved herself as hardy as anyone at handling a full workday of co-worker vexation. She blushed at the Chippendale lookalike singing telegram but held her ground. The worst of any birthday was the on-air comments, because the entire city was privy to these. The day’s cruelest came from Peter Hargrove, who congratulated her on just having gotten in the last of her permanent teeth.

It wasn’t until noon that the day took its turn for the worse, and Paul was in the booth when it came. Fresh into his shift and finishing up with five back-to-back tunes and doing a passable Clint Eastwood/Dirty Harry voice, “Did I play six songs, or only five…?” He punched up a commercial and was loading the CD when he noticed Sherry in the doorway.

“What am I going to do, Paul?” Spoken with all the plaintive hopelessness of a child summoned to the principal’s office.

“About what?”

“Lunch.” She leaned into the doorjamb, tugging at the twist of braided hair coiled over one shoulder. “Popeye says he wants to take me to lunch for my birthday.”

“He’s finally found a cause worthy enough to stick a crowbar into his wallet. You should feel flattered.”

Her small nostrils flared. “I’m serious, I don’t want this. Would you want to spend an hour across the table from that man?”

“Popeye in full feeding frenzy, you have a point.”

“What am I going to do, I can’t flat-out refuse him.”

“Okay, okay, give me a minute to think.” Paul frowned, performing control board tasks by second nature, hands guided by instinct. Then he slumped back into the chair. “Have you told him you have other plans?”

She rolled her eyes. “I can think of something like that on my own, thank you. He wanted to know what they were, if they could be changed.”

The man’s audacity continued to amaze, the pushy bastard. “What’d you tell him?”

“The phone rang, and it was for him. He took it in his office, and I guess he’s still there. I don’t know what to tell him when he comes out. Because I don’t have other plans made.”

“So let’s dig you up a lunch date,” Paul said, and she nodded eagerly. “How about a chaperone? Tell Popeye he can come along if he wants to and hope he backs out. You save face, and even if he tags along, you can stick him for the extra meal. You can’t lose.”

“You’re a genius.” She bounced over, a peck on the cheek. “Not Cliff, though. That would be worse than Popeye alone.”

He pointed out the door. “Go hide in the john for a few minutes, I’ll see if I can find you a prior engagement. And you’ll owe me, I will collect on this someday.”

He went forth a minute later, the CD programmed to cover his absence for a song or two. The deities of fate and interoffice politics must have been smiling down benevolently. The sales geek bullpen held out the most hope, and his second attempt was game for the idea, sales manager Nikki Crandall saving she would act as the third wheel. Popeye got word of these other plans moments later, a close call, and while it turned him grumpy, it didn’t stop him from making it a threesome.

It was one-thirty when Paul caught the lowdown on the results, Sherry back in the doorway, a wraith with hollow eyes. No more simple discomfort, what am I going to do, not this time. This time she was near tears but wouldn’t let herself go, hanging tough. She spoke clearly, half intimidated, half enraged.

The ruse had begun with promising success. Popeye insisted on driving, and while his BOSSMAN vanity plates were ostentatious, after all, it was his gas and parking fees. Riding shotgun, Sherry turned back to Nikki and the two of them maintained a spirited conversation on anything Popeye might find exclusionary. Dresses. Makeup. Diet colas. The new Cosmo and Vanity Fair. Popeye didn’t stand a chance.

He took them to the Fedora Cafe inside Union Station, and everything fell apart within five minutes, when they ran into an account of Nikki’s. She had just tried Nikki at the office not ten minutes before, and had to talk to her before a flight to Boston in two hours. She would even go so far as to have Nikki’s lunch catered in and pay for a cab ride back to KGRM.

She couldn’t refuse. And Popeye, ever the businessman with his eye on black ink in the ledgers, looked downright ecstatic.

Before you could say sexual harassment, it was just the two of them. A discreet table, the clink of silver on china, the ghosts of murmured conversations drifting past. And the unbridled leer of Vince Atkins’s eyes as he told her what a shame it was that they’d not done this sooner, that they hadn’t gotten to know each other very well during her year at KGRM. He dangled the possibility of what he termed a lucrative raise. He waxed sensitive and philosophical about the perils of a young woman without a college degree who, heaven forbid, should find herself jobless and with a poor recommendation from her first and only full-time employer.

Because, in Vince’s words, “I’ve got a very special position in mind for you. And if you’re a smart young lady, like I think you are, you’ll assume it,” after which he eyed her over the top of his vodka martini. He mentioned a predilection for homemade videotapes, and over the glass, encircled by his cigarlike fingers, his eyes gave mere hints of further indignities. She had sat there, agonizingly queasy, but curiously numb, as well, thinking, It’s my birthday and I really don’t need this, how could a job I love so much go so wrong?

“The whole thing was just one big sick scheme to get me away and proposition me,” she said. Sherry had wandered over to the album racks and was running one salmon-colored nail along the spines.

“What did you tell him?”

“Nothing yet.” She hugged her arms around her chest, a retroactive shield against Popeye’s leer. “Not that I would even consider doing anything with him. I don’t even get coffee for him.”

Paul sat up, pleasantly surprised in this strange moment. “And you do for me?”

A quick smile, a tight shrug. “Don’t let it go to your head. I can stop anytime without notice.”

The booth felt supremely odd, Sherry’s refuge, last place in the station she felt comfortable, an Alamo of sexual politics. And here he was again, Paul Handler, brother confessor playing the platonic soundboard again. It was no burden. The sight of her fanned all the right flames within him, and he could feel a hot pulsing in his cheeks and hands that longed for release, to raze Vince Atkins into a mound of ashes.

“How about nailing him on sexual harassment charges?”

Sherry violently shook her head. “No, he was a clever son of a bitch about this, I’ll give him that. No witnesses, so it’s just my word against his. And he didn’t say one thing that was overtly a pass. It was all double-meanings, and that — that f

ilthy look he was giving me. He’d claim I was just misunderstanding everything he was saying. I couldn’t prove a thing.”

She talked, she fumed, she tried to get some of it out of her system. Until she had been in the booth as long as she figured she could get away with, then began the last mile back to her desk, her final comment being that she did not want to have to leave KGRM.

Nothing he could do in the meantime, so Paul let it simmer, back burner, throwing himself into the remainder of his shift with a vengeance. Until the matter could be pulled off again, in full boil.

Crossroads. How to handle this? As with his dual function at the hospital, moral support alone seemed woefully inadequate, not when he was capable of more. Not to act would be far worse than being incapable. Yet he didn’t wish to overstep his bounds. Sherry was bright, she was no pushover, she needed no Lancelot to come riding to her rescue.

Hell with it. Something like this was anybody’s ball to play. While Vince Atkins may have been their boss, he was no Caligula with absolute power and authority. If he needed a reminder, so be it. Paul was comfortable being the one.

Strange. In the past several weeks, he had experienced a steady decline in regard for all those people who, for whatever personal cowardice, slinked away from the line of fire, applied thumb to rectum, and waited in the shadows until trouble blew over. Sure it was a cranky outlook, but he could live with that. He would wade in where fools feared to tread.

Even so, he chided himself for possible brain damage on the trip to Popeye’s office. Might as well just stroll on in, plunk his scrotum onto the man’s desk, and hand over a mallet. It would at least eliminate the suspense of waiting to see how much of a ballbuster Vince would be.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

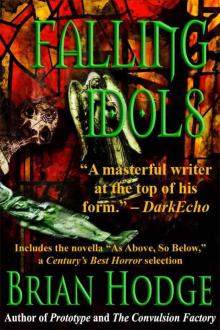

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols