- Home

- Brian Hodge

Nightlife Page 16

Nightlife Read online

Page 16

He wrapped his hand around the arrow shaft and gave a tug, and all it accomplished was snapping the shaft from the bamboo tip. He looked down, wishing he had taken time to put on a shirt. He could see that razor-sharp arrow tip punching right into his belly. See the puckering wound as it drooled blood down his side to stain his slacks. He started to slide forward on the bamboo, maybe he could free himself that way. Agony, sheer agony. Every fraction of an inch seemed to grate on something inside. Especially deep within his back. The thing was barbed.

No telling what it was hung up on inside.

Escobar, now sweating profusely, looked up in fear into the merciless eyes. They had not changed.

“Money,” Escobar rasped. “I have lots of money. I can make you soooo rich.”

The bowman paid him no attention. “You stay inside,” he said to the girls. Gesturing to the stateroom They backed farther in without complaint, and Escobar felt even more alone in a world that had already become too painfully lonely.

The bowman shut the scorched right door. Then gripped the handle of the left and pulled it forward as well. Escobar shrieked. He pedaled with his feet to keep up with it, lest he stumble off balance and fall. Leave an intestinal ticker tape behind as he fell. The doors latched.

And then, the final insult upon injury—

Vanessa and Tracy locked the doors from the inside.

He danced a careful series of steps. Wasn’t enough that he was pinned to the door like a butterfly to a collection board. Now the heat from the burning Jess was getting very uncomfortable. The smoke nauseating.

“Money?” he tried again, weakly.

The bowman kicked the Luger behind him, farther up the hall — no hope now. He yanked the wet towel from Escobar’s face, held the machete along his neck. It was warm, slick. Already used.

“Green powder,” said the bowman. “A man named Hernando Vasquez gave it to you.”

Escobar bobbed his head, eager to please. “Yeah, yeah, that’s right.”

“You tell me where you have it. And I go.”

“Oh, paisa, man, I wish I could help you.” Breathless, he was panting. Frantic. “You’re two weeks too late. I sent it away. Come on, paisa, you don’t want to hurt me like this. We got some of the same blood inside, don’t you see my face?”

“I’m not your countryman,” said the bowman, and Escobar’s hopes for appealing to some kindred heritage died.

The Indian grabbed the arrow in his shoulder, gave a wrenching twist. Escobar screamed. He’d rather his arm fall off than endure that again.

“Where is the green powder now?”

“I sent it to Tampa! You know where Tampa is, everybody knows where Tampa is!” Escobar felt blisters rising on his ankles.

“Who has it? His name.”

“Tony Mendoza, Tony Mendoza!” Dear lord, his pant legs were starting to catch fire. He thrashed one leg in the air to try and snuff out the flames.

“Where do I find him?” Another twist of the shoulder arrow.

“I don’t know, I swear it!” Wrong answer, he knew it.

The bowman sliced a shallow gash down Escobar’s left pec, split the nipple dead center. Both hands had been trying to hold his insides together, but he let go with one and flailed at his tormentor. Got a nasty chop across the forearm with the machete.

“Where do I find him?”

“I don’t know I don’t know!” Escobar thought he could never die quickly enough. “He’s in Tampa, fucking Tampa now please please put out that fucking fire man PUT IT OUT PUT IT OOUUUUT!”

With a guttural cry, the bowman wound back with the machete, cocked, ready to fall. Escobar scrunched his eyes shut, didn’t want to see the blow. Felt his legs blister, the flames from Jess having crawled all the way up to his knees. Eating toward bone. Toward thighs. Toward genitals.

He waited, welcoming the fall of the blade.

But it didn’t come.

And when he opened his eyes again, the bowman was already halfway down the hall. Sitting on his haunches. Watching me burn. Greasy smoke wafted up into his face, the sizzle of fat. Escobar drummed his smoldering feet on the floor. Anything to distract from the pain. The fire was feeding on itself now, halfway up his thighs, his slacks charred tatters. Drop and roll — that was all it would take.

Yet he still couldn’t work up nerve to tear loose from the arrow.

Flames, broiling his legs into crisped hide. His voice, raw and hoarse by now. Anything was better than roasting alive from the ground up. He braced his palms against the door behind him. Took a deep breath.

And launched himself away from the door.

Well…

Most of him, anyway.

Kerebawa was halfway across Miami by dawn. Dressed, once again. Heading northwest. He had looked at the full Florida map opposite the Miami side. Had found Tampa.

The trail of the hekura-teri was growing colder. But he knew he should at least try. He had nothing else to do. And so he walked. With his tied cloth roll and bundle of sticks, now three in number, he cut a small and lonely figure.

By midafternoon he was free of the city and was in areas less congested. Found himself in a small town called Opa Locka. It was good to have the crushing frenzy of the city behind him, good to feel the open ground beneath his feet more often.

In late afternoon, Kerebawa took respite in a small park area, foliated thickly, plenty of palms towering overhead. Within this emerald theater, he rested. Sniffed some ebene in hopes that it might open his eyes, at least in this tiny replica of home. Show him what to do, where to go, what to hunt for.

There were mysteries, still. And his noreshi, the hawk, still had not returned. But when he looked in the distance to the northwest, toward Tampa, he saw something else.

An eagle, struggling with broken wings.

And as the heat of the day and the draining effects of the ebene sent him seeking a bed of ferns, he smiled. Gave a self-satisfied nod. For at least he had something once again to follow.

Chapter 13

LIFE GOES ON

At her tilted drafting table, April poked her tongue out while she worked. Frowning in concentration, working that tongue tip at the corner of her mouth. Justin thought she probably wasn’t even aware of doing it. Amazing, all the little habits that characterize us that for go forever unrealized.

He enjoyed watching her work, tried to be unobtrusive. Just sat in a chair several feet away, a Killian’s sweating on the hardwood floor beside his chair leg. Can’t leave the bottles alone, can I? he thought. But I’m handling it, it’s okay, it’s not out of control. April was doing some cartoonish graphics for a plant rental and maintenance firm. Big business down here, he gathered — expert foliators for office space, for execs too busy to worry about their own green thumbs. Or lack of them. With as many plants as he had sent to an early mulch-grave, Justin figured his own thumb was brown.

April worked in sporadic bursts. A flurry of lines and strokes, then periods of appraisal and contemplation. Pulling back to view at a distance, leaning close for microscopic scrutiny. Her hair was tied back in a ponytail to keep it from falling onto the paper.

And he watched, committing her movements into an overall gestalt. You never truly know someone until you know how they move. It’s not enough to call to mind their face, body. You have to understand the way they move. And with April, he wanted to know it all. Because she, dear young woman, had moved him.

At the same time, he had to wonder how long it would have been before they reached this stage had Erik not died. A week ago he hadn’t even known her. A week ago she was mere fantasy, an image on Kodak paper. Without Erik’s murder, they still would have reached it, probably. After another week, maybe two, perhaps a month. They had been on their way. A moot point, however.

Quantum leaps had been made this past weekend. Heightened emotions squeezed out by a pressure cooker of sorrow, and vulnerabilities so blatant they might as well have had bull’s-eyes painted on them. They had turned to each

other so quickly it was dizzying. Maybe that was healthy, maybe not. The more cynical of the world might have said they were merely using each other as an antidote for grief. Perhaps they were.

But he refused to believe it.

“So what’s it like?” she said, looking up from her table.

“Erik’s hometown?”

“Uh-huh.”

It was a continuation of a conversation put on hold ten minutes ago, before the graphics had taken over again. He understood perfectly. Even did it himself, back-burner a conversation while in the midst of writing something, expecting it to still be warm when he was ready to pick it up again. The mind in the act of creation bridging the time gap as if it were an eyeblink. It had always bugged Paula. Creative sorts generally belonged together, if for no other reason than they were more apt to put up with one another’s quirks.

Erik’s hometown. Shepley, Ohio.

“I was there only once, during college.”

“Once is enough to know.”

Justin shrugged. “It’s little. About eight thousand people. Kind of like Garrison Keillór’s Lake Wobegon — you get the idea that time sort of forgot it. It’s the kind of place you might have expected Norman Rockwell to retire to.”

April smiled, rubbed her eyes. A bit red, strained. “He hardly ever talked about it.”

Justin drank some beer. “Erik had a love-hate relationship with the place. You know, once he was past a certain age and all, and it just wasn’t enough anymore. But still, he grew up there.” Justin smiled toward the floor. The ache within — oh, that ache. “He’d gotten too big for the town. Not in an ego sense. Just in what he needed and couldn’t get there.”

“Will it bother you much going back there again?”

“Probably.” He folded arms over chest, shut his eyes a moment. He had spilled a lot tears over the past three days, to be dried by April. Just as he’d dried hers. “I know his parents want him buried there, but it doesn’t seem right, in a way. That place isn’t him anymore. He didn’t much fit in even when we were in college. The gap only got wider after that. He shouldn’t have to stay there forever.”

She tabled her pen and got up from her chair. Crossed her artfully cluttered office and stood behind him. She circled his chest with her arms. Kissed his head, then turned her cheek to rest atop it. She patted a hand over his heart as he gently gripped her forearms. Hand over heart, patting, patting.

“He won’t all be there,” she whispered.

April worked another twenty minutes, then checked the time. Nearing four o’clock. She had put in a long day. She clicked off the swivel lamp hanging over her table.

“I need to go to the travel agency for our tickets,” she said. “Want to tag along?”

“Sure.”

Justin stood up and stretched. Any trip sounded good. He’d not been out of the loft all day. For that matter, he’d spent most of yesterday cooped up too. Had briefly stepped outside yesterday morning for her Sunday Tribune.

They put on shoes, and he wondered how long things would last this way. He could start feeling like a kept man very quickly. Justin Gray, gigolo for hire. If she can still walk, I don’t know my business.

April went through the ritual undergone anytime she left her office. Weighting down loose papers so stray wind wouldn’t scatter them. Shutting the windows at this end in case of sudden monsoons. Last, she turned on the answering machine for her separate business line. All set.

And hand in hand, they left the apartment.

Lupo liked to think of life in terms of boxes.

Packing crates for life’s biggies, matchboxes for the little things. A place for everything, and everything in its place. Disorder was his mortal enemy. Of course, when things began weaseling from their boxes, that was when he did his best work. Keeping those crates in good repair. He was, he realized, a stevedore on the S.S. Mendoza.

He sat parked in the same nondescript Olds they’d used to snatch Erik Webber. Alone, at curbside. Just as he had been for many hours, the same weeping willow branch bobbing before the windshield. The car’s windows were opened up full, the breezes pleasant today. The weekend’s humidity had dipped to humane.

Behind the wheel, he fingered a box of nine-millimeter bullets. Not to use, just for fun. He opened the box, slid out the Styrofoam block. Perfect bullets in perfect regimented rows, gleaming brass. The Styrofoam a perfect snug fit within the box. All of life should fit together as nicely.

Things had gotten too loose around the edges lately, as far as he was concerned. This happened periodically, no way around it. With Tony running the show, it was inevitable. But then, nobody made advances in any business without occasionally treading over risky ground. It was just that in some businesses, the consequences were more permanent than in others. Which was why they paid so well.

Skullflush was, he fretted, a potential bastard to keep a lid on.

Erik Webber dead, now this. Eliminating players in the thick of the game was one thing. Planning the elimination of those on the periphery — well, that was when troubles began to rattle at those box lids.

Justin Gray. Tony hadn’t been able to turn loose of him. An untidy frayed end that needed clipping. Tony, ever since Erik had bidden a farewell to arms, had run things over in his mind. How and where to find the guy.

Tony had once more plied a girl he knew who jockeyed a computer for GTE. Still no new phon listing or scheduled hookup for a Justin Gray. Had he gotten his own place, as Erik had said, it seemed unlikely he would ignore a phone. Scratch that off as a lie told to protect a friend.

Then he’d remembered April Kingston. And a slight inconsistency.

Tony had questioned her last week about the guy. She said she didn’t know much about him. Okay, fine, he’d had no reason to doubt her at the time. But once Angel had spilled the beans, Tony had to reconsider. Justin and April had looked pretty chummy at Apocalips. Now, if Angel had known Justin was Erik’s pal and not Trent’s, shouldn’t April have known too? Sure. Ipso facto, a withholding of information. And she had to have a reason. Maybe even a personal one. Hence Tony’s late-Sunday-morning decision that perhaps her apartment should be watched for a while. Just in case.

Well well well. Pay dirt, and this was only Monday afternoon. There they were, hand in hand as they left her building. Going for her car.

April, April. ‘Twould appear that she had been less than upfront with Tony. This was not a healthy thing.

Lupo slowly keeled over across the front seat as they left and pulled onto the street. No sense in chancing an unwanted discovery. He straightened up moments later and let them run like rabbits.

He fired up the Olds. Not to follow, but homeward bound. Tony would be most pleased to hear what he had to say.

Justin and April flew out of Tampa late Tuesday morning, packed for a forty-eight-hour layover in Ohio. They touched down in Cleveland, and from there they rented a Capri from Avis and puttered southwest on 1-71 some sixty miles to Shepley. It was five miles off the interstate, and they checked into a motel near the turnoff.

They slung clothing onto hangers, divided the shiny silver bar near the bathroom into his and hers sides. Generic motels like this always made him feel a little sad. Forlorn way stations with no souls, when you wished you were somewhere else. April seemed to sense it and stripped the SANITIZED FOR YOUR PROTECTION band from the toilet. She put it on like a headband, and this made him laugh.

Shepley was like some overgrown village in the middle of farm country, sprouting up from land as flat as an ironing board. It was the kind of place Justin could imagine John Cougar Mellencamp singing about, somehow managing to find the heart in this part of the country. This town of white picket fences and White Protestant Values. This town of gossiping phone lines where a good scandal might get years of mileage. This town of teenagers who cruised out of desperate boredom, and of veterans who loved their God, country, children, and beer, not necessarily in that order.

Erik’s parents had flown do

wn on Sunday to claim his body, had returned the next day. Tuesday evening after the funeral home visitation, Erik’s display with a prosthetic and a glove, the Webber house was like a miniature Grand Central Station. For those who truly cared, and those unable to pass up a chance to show how sympathetic they were. If there’s anything we can do … Justin grew sick of hearing the phrase. Their kitchen swelled with food and drink, and casseroles sprouted like mushrooms.

Justin and April retreated for a while to Erik’s bedroom, probably unchanged for years, merely dusted and vacuumed. A shrine to a younger Erik, high school vintage. Pictures on the walls, Erik on a track team, and shooting his camera for the school rag, and looking silly and dated in a leisure suit with some unknown girl the night of a homecoming dance. A whole life lived, however short, before Erik had ever known such a person as Justin existed.

He sat on Erik’s bed, and April sat beside him. This was where the whole houseful should be. Out there, with the casseroles from hell and the friends and neighbors playing catch-up with one another’s lives, it seemed that Erik was an afterthought.

The funeral was Wednesday afternoon; it pulled a good crowd. A Lutheran church, and it had air-conditioning. The minister possessed some tact and didn’t try to explain it all away as God’s will. This Justin appreciated. Maybe if he himself met an early expiration date, they could get this guy to launch him into the hereafter. If, say, cirrhosis caught up with him, or his luck ran out while driving home with a buzz on some night.

Or more likely, if he bit off far than he could chew once they got back to Tampa.

Burial was on the edge of town, along the same stretch he and April had driven in on. Some small, peaceful cemetery atop the gentlest of rises, with a few desolate trees and a good view of the highway. A scattering of fast-food places on toward Shepley. A Burger King and a cemetery, how quaint. For those who must eat and run, he decided. He had to think of something while serving as pallbearer.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

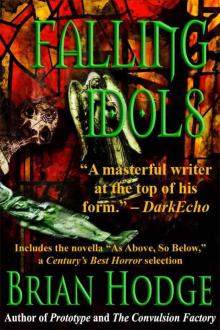

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols