- Home

- Brian Hodge

The Darker Saints Page 2

The Darker Saints Read online

Page 2

“Pass,” Finch said. Pride was at stake.

“Naw, naw, you don’t be frownin’ at me. My wife’s cookin’ up a crawfish étouffée, and I do believe we gone have plenty extra. You just keep it settin’ right there, son.”

Finch and Dorcilus slumped down into their chairs, drank the Loners in weary limbo. Long day, tiring day. Hot day. Finch’s clothes reeked of dark water and fish and sweat. It wasn’t altogether unpleasant, in a heady macho way.

“Got an idea,” Finch said. The beer was nearly gone and had geysered straight to his head. Blame it on the hours of sun. “Let’s trade secrets, okay? One of mine for one of yours. Sound fair?”

Dorcilus eyed him over the top of his own bottle, then his cheerful dark face broke into a toothy grin. “I’ll play.”

“Me first. Okay.” He’d known all along what he would ask. This evening it seemed especially important. “How come you really came floating out of Haiti six years ago? Forget the rest of the guys on your little flotilla. Just you. I don’t believe you were an enemy of the state any more’n I’d believe it if you told me you were the world’s first black pope.”

Dorcilus rinsed his mouth with Texas brew and sighed. Shook his head ruefully, finally snared in a lie. “I have enemies there, all the same. This is true.”

Finch grinned, scenting blood. “Why?”

“There was this woman. Alliancine was her name, mmmm. She was a fine one. A woman the loa would send to earth to tempt a man.” He smiled, memories of passion, then it cleared. “She was married to an officer of Duvalier’s Tonton Macoute, and this I did not learn until too late. Until he had already learned of me.”

Finch nodded. This was it? He’d been expecting more, something that would cough up a clue as to what this trip to Bayou Rouge was all about. And a long-ended game of hide-the-sausage with the wife of an officer in the Haitian secret police — under a regime that succumbed to revolution just months after Dorcy had fled, no less — did not offer much. Unless Fonterelle was snow-jobbing him again. But he didn’t think so. The nostalgia of flesh and passion showed too plainly on his face. Not like the chest-pounding boast of his having been some sort of revolutionary, easily a transparent lie from the outset.

Adultery, huh. Zip the pants and get the hell out of Dodge. Now and then were obviously unrelated.

“And now you.” Dorcilus aimed the empty brown bottle at him with a sly grin. “The truth this time. How did you get your limp?”

“I told you already. I used to race motorcycles and I took a bad spill. Lucky to get out of it with my leg in one piece.” Dorcilus wagged a chastising finger. “When you passed out last weekend after those last beers? I checked your driver’s license.” Triumph, smug and annoying. “You are not classified for motorcycles.”

Finch wilted in his chair. Oh man, now that had been low. Who would’ve thought anyone would be so devious as to check something like that? Well, he supposed the truth wouldn’t hurt. Not in this case, at least. It would never go beyond this table.

“Couple years ago I had this truck. Pickup. One of the fuses went bad and the stereo wouldn’t work without it and I didn’t feel like stopping to buy a new one.” His cheeks started to go red with embarrassment. “Turned out that a twenty-two long rifle bullet fit the slot perfect. I think, great, I’m rolling. Except the electricity heated up the bullet and it went off and shot me in the goddamn knee. There. Are you happy?”

He’d expected another gale of laughter to weather, just the way to round out Pick-Nn-Finch Day. But there came nothing of the kind. Dorcilus merely nodded, contemplative, in a caring sort of manner.

“I am very sorry,” he said softly. “I have seen what bullets do to people.”

Hell’s bells, now why did he have to go and say something like that? Why couldn’t he have been the cocky sportsman who’d hauled in all those fish earlier? He wasn’t making this any easier.

“Yeah, well, no big deal.” Finch tried to shuffle the incident into insignificance. “Those’re little bullets, anyway.”

He sat and fumed his way through another overpriced Lone Star. The crawfish étouffée hadn’t yet made it to the table, and he had to wonder about that. Maybe just a ruse to give them a reason to wait. If so, it was successful.

And no longer required.

Finch heard it before Dorcilus, but then, he was expecting it. Listening for it. A low, rhythmic beat of whirling wings, swelling out of the northeast. A sound that would give any Nam-vet in the place, had there been any, cause to pause and reflect.

Air cav.

The Cajuns scarcely paid it any attention and continued to drink without breaking stride. Belisaire’s walls began to vibrate as the helicopter neared, and the alligator hides wavered while dust sifted from low rafters.

Finch watched Dorcy out of the corner of one eye, saw his barest whisper of unease, a sense of things awry. Best to undercut it.

“If that’s Eye In The Sky traffic news, they’re sure as hell lost.” Finch laughed, reassuring. “Go check it out?”

Dorcilus relaxed, and that was just fine. They got up, crossed for the door, and Finch knew that every eye would be on them. When he nudged the door open, fresher air cut through the dim oppression of the bar. They wandered over beside Finch’s Chevy, looked in the direction of the helicopter.

It had settled in a clearing between two rows of substandard Bayou Rouge housing. A sleek white craft with polarized windows, impenetrable to the eye; trimmed with two shades of blue, sky and navy. Its pilot killed turbine power and the rotors whined while gearing down. Propwash diminished, and there it sat on its landing frame, seventy yards away, like some kind of high-tech wasp.

Really a shame about Dorcilus. Truly a nice guy. Finch had to quash down a flicker of conscience.

A door popped loose on the helicopter’s passenger cabin, swung open. The first guy out was a burly fellow; tan chinos, blue shirt, mirrored shades. A second appeared, a rifle slung by a strap from one shoulder. They appeared to wait, deferential to some higher authority.

And when he came, he stood a good head taller than the first two, though reed thin. He was a study in white: suit, tie, Panama hat … and skin. The only splotch of color was the red shirt. The albino looked their way, while Finch thought with queasy recollection that, in his case, the blue eyes seemed even weirder than pink. His name was Terrance Fletcher, but there were those who called him Eel, and it fit. The man had to be the most supremely creepy guy ever to tread Louisiana soil.

The rifleman shut the chopper door and the trio set off on foot, closing in with great deliberation. Finch peeked at Dorcilus to see how he was faring. The Haitian was more than frightened; the man was petrified. Dorcy pointed at Eel while a slow, dark stain spread across the crotch of his pants.

To inspire that kind of fear? Now there was power.

“Djab blanc,” Dorcilus muttered, voice cracking. Then it rose to a terrified shriek. “Djab blanc!”

Finch hit him with a sad, knowing twist of the mouth. Shook his head ruefully. “Sorry, bud. It was nothing personal, really.”

Dorcilus gaped like any of the innumerable fish he had caught that day, and just the thought of that humiliation made Finch feel a little better. Then he noticed a twitch of the Haitian’s legs.

He’s gonna bolt —

Finch lunged for him. Not that Dorcilus could get very far down here in the waterlogged boonies, but you never knew, it might score Finch a few points with the right people if he saved Eel a little legwork. He lunged —

And missed.

Finch went stumbling against his car, his knee picking the most inopportune moment to crap out. Next thing he knew, Dorcilus had seized his fat stringer of fish from the ground and swung it with gusto. Finch took a face- and mouthful of catch of the day and hit the ground hard, spluttering. He hated sushi.

Through watery eyes, he saw that the two henchmen from the chopper had broken into sprints. They charged, leaning forward from the hip, like ex-gridiron jocks chasing

old glories. Behind them, Eel maintained an unhurried gait, confidence high, with all the time in the world.

Dorcilus had gone loping toward the nearest tree line and thickets of bayou underbrush. An amazing display of energy, given their day in the kind of humidity that sapped your strength sure as a leech. Finch struggled to right himself against the Chevy’s fender, and had to admire the guy’s survival instincts. The bayou didn’t offer its shelter easily. It tested you with dark water and muck and mire, with primeval woodland, with alligators and snapping turtles and snakes as thick as your wrist.

And, so local levity probably had it, those were its good points.

Dorcilus went splashing through a ditch clotted with mud and stagnant water. His legs churned up flying muck, and water soaked his shirt. Finch watched it all from behind, listened to his high-pitched panic, raw and inarticulate and guttural. The mud had slowed him considerably, left him as stationary a target as he was likely to present.

One of the riflemen dropped to his knee, swinging the gun up. Sighting in. One shot.

It didn’t sound quite right, not like any bullet Finch had ever heard. He saw Dorcy arch and stiffen as he took it in the hip, then knew why.

A dart? Tranquilizer dart? It was the best he could figure.

Finch held white-knuckled to his fender as the two enforcers strode past him as if he weren’t even there. Dorcilus floundered, wept, struggles weakening by the moment. In despair, his cries rang with loss and damnation.

This wasn’t going at all as expected. Been thinking, boom, they’d take the guy down in one quick burst of gunfire. Either pitch his body into the water, or haul it back to the chopper to prove to someone that Dorcy was indeed in the past tense. But this? When Eel halted several steps away, Finch wasn’t sure where he most dreaded looking.

“Good job,” Eel said. His eyes were dispassionate in a face of composure. Smooth white flesh, white-blond hair, eyes like sapphires. The chiseled cheekbones and jawline of an aristocrat. He was rather handsome in his own striking way, but just creepy. Any woman he bedded, Finch would never want to touch, regardless of how stellar her attributes. This guy would leave too much of himself behind.

“Thanks, Mr. Fletcher.”

“Got some mud on your cheek.”

Finch felt like a preschooler as he wiped it onto a sleeve.

Dorcilus was pulled free of the ditch with a wet sucking sound, then toted back, one man at his feet, the other at his shoulders. He could do no more than twitch, and his voice had been reduced to a piteous moan, eyes gazing off into some realm beyond Finch’s perception.

Once the men carried Dorcilus farther into the shantytown of Bayou Rouge, they carefully laid him out in the coffin atop two sawhorses. Passing it earlier, the young craftsman planing it smooth, Finch had had no idea. Dorcy’s shirt was stripped off, then his mud-caked shoes, then they used a knife to cut away his soiled trousers. Everything went into a wet heap below the coffin.

And then the going got truly weird. Finch longed to bail out and couldn’t, had no choice but to clutch that fender and watch.

Eel turned his full attention to Dorcilus’s living corpse. From a pocket he produced some type of rattle, a primitive-looking ceremonial thing, woven with brightly colored beads and several bleached bones that looked to be small vertebrae. Eel shook it over the naked body in intricate patterns; beneath it, Dorcy was racked with final tremors before total paralysis set in. But his eyes remained wide, staring, sheened with panic too intense to think him less than wholly aware of every last thing around him.

Finch had heard the rumors about Eel, that the guy was into major weirdness. Nothing had ever been spoken louder than a hush — walls could have ears. Finch had dismissed it as so much mystique, maybe some superstition thrown in, blame it on Eel’s otherworldly visage.

Now? He was a true believer.

While Eel went through his ceremony, the rifleman jogged back to the chopper. Brought back a white china pot, small, wouldn’t hold much over a half gallon. He removed the lid and stood like an acolyte while Eel pulled a bone-handled knife from within and bent toward the coffin.

Finch beat the urge for heaves only when he realized that butchery was not the intent. The albino was carefully slicing away locks of hair from Dorcy’s head, chest, left armpit, pubic thatch. Once these were collected, Eel deposited them in the center of a green banana leaf unfolded from the pot. He next trimmed away parings from Dorcy’s left fingernails and toenails, moving with brisk surgical precision. The nail parings he sprinkled into the clipped hair, and by then one of the Cajuns had brought him a pure white cockerel, yellow legs trussed with a thin cord. It squawked unhappily, dangling upside down in Eel’s fist, and the Cajun beat a quick retreat. Little wonder.

Eel moved with neither mercy nor hesitation. He pried the cockerel’s beak open, ripped out its tongue between his forefinger and thumb. Its wings he snapped, and as it twitched, Eel twisted off its head with one savage wrench. Blood gouted from the stump and Eel shook the bird over the open coffin to sprinkle Dorcy with red dew. He tore into the carcass with a doubled fervor, ripping out crude tufts of feathers. Some he dropped into the coffin, others he drizzled with blood and mixed with the hair and nail parings. He hurled the dead bird to the ground, where it hit with a wet thud.

Finch, watching with ragged breath … he dared not even move. Eel’s white suit was a wreck, and all Finch could think about for a moment was his fucking cleaning bills. The man’s white face was speckled with blood and gleaming with an intensity Finch never wanted to understand. He held his breath while Eel knelt, carefully rolling the banana leaf and its grim trinkets into a neat bundle and stuffing it into the china pot. Eel rattled the top back into place and tucked it under one arm as he rose and glanced at his two associates. He nodded down toward the coffin.

“Bury him,” he said. And smiled.

Eel pointed toward a distant tree line, toward the gathering dusk at the edge of town. The mossy branches were random arches in a gloomy cathedral. There. Finch hadn’t noticed it before, but just within the trees hulked the unmistakable mound of earth from a freshly dug grave. Awaiting only an occupant.

The two enforcers lifted the coffin lid from the ground; hammers and nails were gathered from underneath. They fitted the lid into place, cutting Dorcilus Fonterelle’s staring eyes off from the last of the dying sunlight.

The sudden racket of hammers in concert was very loud.

Finch was still wedged against his fender when Eel came walking toward him. What to do, what to say, what to think? He wasn’t used to selling out friends for murder, much less for savage rituals and live burial.

The pot rattled again as Eel rested it atop the Chevy’s hood. Couldn’t dare ask him to put it someplace else. The car would feel forever tainted. Time for a trade-in anyway.

“Again,” said Eel, and his voice was gentle, “fine work.” He reached into an inner jacket pocket to withdraw a sheaf of crisp bills. Stuffed them into one of Finch’s pants pockets with the intimacy of a Bourbon Street vet tipping an admired dancer.

“Glad you’re happy.” There. Finding his voice wasn’t as difficult as he feared.

“That I am.” The bloodied face hadn’t lost one shred of composure. Like a doctor who had just sutured off a nasty bleeder in the OR. “Working for me, the one thing you learn the quickest is that I reward competence. And loyalty. Just ask him.” A nod to turn around.

Finch did so, saw Emile Duchamp standing inside Belisaire’s doorway. The Cajun appeared quite somber, a far cry from that jovial guide getting a laugh out of Finch’s shortcomings as a fisherman.

“We’ll be back in three days for the Haitian,” Eel said to Duchamp. “Don’t let anything happen to that grave. Or plug up the air pipe.”

Duchamp nodded. “It’ll be safe, don’t you worry.”

Eel looked at Finch, then cocked an eye toward the pair hammering the lid on Dorcilus. “I’ve got another job for you if you’re interested. Why don’t y

ou come with me.” His voice dropped to a hush. “Not for their ears, if you catch my drift.”

Finch said sure. What, he was going to refuse? Not this man. Unthinkable. He fell in beside Eel, a respectful half-step behind, and they started off for the docks.

“You’ve done business here before, I guess,” Finch said. Show the man he could think on his feet.

Eel nodded as they covered the well-worn path. “For years. We’re the economy that keeps these people solvent, without any worries. They appreciate that. And we don’t ask that much of them.”

“Company town, huh?”

“Of sorts.”

They reached the docks, boards groaning underfoot. A few timbers were beginning to look spongy. Before them lay a primordial panorama of swampland — dark water and somber trees, shrouded in a hazy twilight mist. Land that time forgot. Dinosaurs could come bellowing in from the horizon and you wouldn’t be surprised.

Despite the heavy air, Finch was breathing easier. Gotten a little shaky back there when Dorcilus was going down, but he was back on track again. More work already — he must have duly impressed the creepazoid.

Finch turned back to Eel, ready to hear the particulars.

Found himself staring at the small muzzle of a pistol.

“Hey.” Finch couldn’t believe he was going to die with such a stupid expression on his face. Loss of pride was worse than his sense of betrayal. And after he’d worked so hard at being a stand-up guy.

Eel fired once, the gunshot a thin crack, and the bullet caught Finch in the hollow of his throat. He choked, swayed on his feet with senses reeling. Such a tiny bullet, now there was unwelcome irony. Just like when he’d capped his own knee.

Eel stepped forward, smoking pistol in one hand, and plucked the bundle of cash from Finch’s pants. He left the pocket hanging inside out. He then slapped an open hand across Finch’s face and gave a shove that toppled him backward into the water. The splash wet a square yard of dock, and Eel stepped to the edge to peer down as Finch splashed ineffectually. Eyes wide and glazed, one hand clutching his perforated throat. The hole wheezed a thin gurgle.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

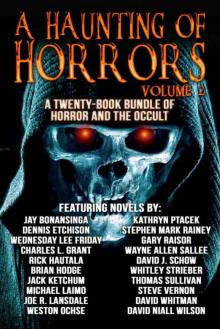

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

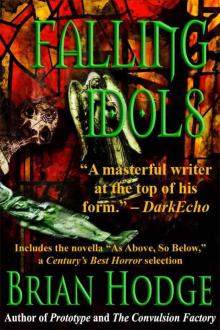

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols