- Home

- Brian Hodge

Oasis Page 3

Oasis Read online

Page 3

Yet that’s not enough to inspire hatred. Pity? Yes. Revulsion? Maybe. We hated him because he was an obnoxious asshole. On our weekend jaunts, he spilled beer and Doritos on himself and us. He laughed too loudly. He told stupid jokes, which made him laugh louder still. And it’s impossible to pick up girls when you’re hauling around this greasy-haired, raving amoeboid in your back seat, bellowing to be heard over the tape player. Short of outright murder, what could we do? Guys like Hurdles make a career of not fazing easily.

Well, Phil came up with an idea.

We coaxed Hurdles out one weeknight in the spring, after he’d had a late band practice — he played tuba, of course — and hadn’t eaten supper. We snared a case of Coors and got Hurdles tossing them down as fast as he could. Eight beers later, he uttered one last mighty groan and cashed in his chips in the back seat of the Duster. Phil stopped on a country road and we clustered around Hurdles like a team of surgeons. We rolled him onto his ample belly. Tugged his pants down. Held our breath.

“Look at that!” Rick cried. “He’s got zits down there, too!”

I snickered. “Anybody for connect-the-dots?”

Phil backhanded me across the shoulder. “Let’s do it before he wakes up. If he catches us now, he’ll think we’re a bunch of queers.”

We nodded solemnly, for that was a fate no red-blooded heterosexual young man wanted. And so with as much speed as feasible, we proceeded to paint Hurdles’s ass blue with ink I’d borrowed from my dad’s architectural supplies when I’d visited him at work that day. After the ink dried, we sealed him back up and drove on, and Hurdles revived a bit later, complaining of a sore belly but otherwise none the wiser.

Of course the moment of discovery had to be public, and Phil had considered this, too. The next morning, all four of us had PE for our first class. We showed up nursing vile hangovers, but sure that the pain was a small price to pay. After class, when we returned to the locker room and stripped for our showers, a naked Hurdles Horton walked toward the showers. To do him credit, Hurdles carried his bulk gracefully, but this time he left three dozen guys doubled over in laughter in his wake. Mystified, he worked his way over to a steamy full-length mirror and performed a clumsy pirouette, and when he saw the problem, his face turned a bright red and he started to quiver all over. Coach Friedman walked in then, took a long look at Hurdles and his electric-blue ass, shook his head sadly, and said, “Chuck … I warn you boys and give you these lectures on VD and it still doesn’t do a bit of good.”

Laughter erupted harder than ever. Hurdles threw an accusing glare at us, pointed a shaking finger, and burbled a few words no one could understand. Then he ran to his locker, gathered his clothes and as much composure as he could, and fled the locker room, his shower forgotten. Much to the dismay of his next class, I’m sure.

Most of the guys were late for their second-hour classes, and for those who needed it, Coach Friedman wrote them late passes. After all, it’s hard to be hysterical and get dressed at the same time. I thought Rick and I would never get out of there. But Phil watched the whole scenario with a detached little smile on his face, as if it had come from a movie he’d already seen a dozen times. But if you looked close enough, you could see that it was surely his finest hour.

We had some grand times together, Phil and Rick and I. And as I look back on those days, one fact can’t change: However close the three of us may have grown, our friendship that began in Mavis Veach’s classroom was born out of fear.

That’s somehow appropriate. Because that’s the way it started to fall apart.

Chapter 3

I always loved Sundays at home. It seemed that Sundays were about the only chance we had to spend much time together, as a family. And as uncool as it may have been for a guy my age to admit it, I was really close to my family — Mom, Dad, my brother, Aaron, two years younger.

The Sunday of graduation weekend was quiet and rainy, the kind of afternoon that yields up warm and pleasant memories that you can look back on, and wonder where those days went. Late that afternoon, I found Aaron staring out his bedroom window at the rain.

“Hey,” I said from his doorway. “You alive?”

He didn’t move. He just said, very quietly, “Pissed on again.”

I went in and plopped down on his bed. “How’s that?”

“We were gonna go to the lake today. Me and Mitch and Bobby.” Lightning flickered outside; thunder rolled; rain spattered the window.

“Not Hurdles?”

Aaron snorted laughter. “Hurdles at the beach? Gag.”

Hurdles wasn’t their friend any more than he was ours. But they needed him. Hurdles could get served, because he looked more or less old enough. Aaron and his friends used to ask me to pick up their stuff, because I had a fake ID and always came through, but I never felt good about it. I worried, too much the big brother. And so I started making myself scarce when I knew they were going out. Eventually they turned to Hurdles. He was always looking for somebody to go out with. The Hurdles of the world usually are.

I leaned back on Aaron’s bed and gazed up at the poster on the ceiling, Vanna White in a two-piece.

More posters adorned the walls, mostly rock bands and starlets whose names are forgotten after their year or so in the limelight. Does anybody care about Pia Zadora now?

“What did you do Friday after graduation?” Aaron asked.

I shrugged. “Nothing much. Late that night, Phil and Rick and I went to a party. I got some good-luck kisses from a few girls there.”

Aaron grinned appreciatively. “Valerie wasn’t around?”

“She gave me the night off.”

“The best of both worlds, huh?”

“Yeah. First we just went cruising. Found a good spot to go to this summer, really secluded. Some housing subdivision that bombed, Phil says. We named it Tri-Lakes.”

“Where is it?”

“About seven miles north of town, off Route 37. I’ll take you there sometime.”

Aaron nodded, then turned to look out the window again, tugging at his fingers, his eyes set in silent complaint about the weather. I leaned back against his headboard, linking my hands behind my head.

“It’s not like you don’t have the whole summer ahead of you.”

Aaron nodded glumly. “Yeah. But this year they’re making me get a job. I wish they’d never brought the whole mess up.”

I made balls out of a stray pair of socks, lobbed them across the room. “You just got your license. You want to drive, don’t you?”

“Sure.”

“So what do you expect to drive on if you don’t earn some gas bucks? Can’t freeload off the parental units forever, you know.”

He nodded halfheartedly. “Allow me my misery, okay?” He pointed out the window and grinned. “It’s all I have today.”

“Have you applied anywhere yet?” I asked.

He flashed me a sly look. “They think I put in an application at a couple of places. But I haven’t worked up nerve yet.”

I pointed a finger. “How about putting one in at Chuck Wagon Steak House?” Chuck Wagon had given me my first summer job a couple years back. It wasn’t a bad job, but it burned me out on beef for a few months. “I bet you could get hired there easy. They’re always looking for fresh meat.”

Aaron wrinkled his nose and left me alone in my burst of intentionally stupid laughter. So I started telling him stories of the days I’d passed there … how a few of us used to sneak boxed pecan pies out with the trash and divvy them up in the parking lot after work. Like how crazy the place got after closing when the manager decided to take off early. Like how much fun we had making coleslaw, doing a John Belushi samurai act with butcher knives and cabbage. It left Aaron smiling by his window, hopefully a bit less reluctant to sally forth and join the world of wage earners.

For my part, I also had a summer job to start in the next few days. Phil and I had snagged positions with the county highway department, filling potholes and holding

traffic signs when lanes were down for repairs. Four bucks an hour and all the dust we could eat.

I headed downstairs, easing down the carpeted steps into the family room. As I had suspected, my parents were asleep. Sections of the Sunday paper lay scattered across the floor and on tabletops. Dad lay on his back on the floor, one arm on his stomach and the other stretched behind his head. Mom sat dozing in the recliner, head canted toward her left shoulder. Her eyes fluttered open and she smiled sleepily at me. I never could sneak up on her. She pointed to Dad and raised a shushing finger to her lips.

“What time is it?” she whispered.

“Almost four.”

She frowned. “I suppose that means people are going to want to eat soon.”

“We could get a pizza.”

Mom pretended to muse it over, but I was sure she’d taken the bait. She was a fiend for Italian sausage. “Okay,” she said. “But you have to go pick it up.” She yawned. “What’s Aaron doing?”

“Last I saw, moping out his window at the rain.”

“He wanted to go to the lake today, didn’t he?”

“Yeah. Doesn’t rain for three weeks, and now look at it. Sorta shot hell out of his plans.”

Mom wrinkled her nose. “Don’t talk like that, Christopher. You know I don’t like it.”

“Sorry, it just slipped out. Damned if it didn’t.” I laughed as she tried to hit me with another disapproving look. “Anyway, what’s the big deal? You have to hear lots worse at work.”

“Oh, you. You’ve got an answer for everything, don’t you?” She shook her head as if I were the worst lost cause she’d ever seen.

But it was an act; she’d seen far worse, time and time again. Work, as I’d called it, wasn’t a paying job. She handled calls on a crisis intervention hotline on a volunteer basis. Doctor Mom, as Aaron and I referred to her when she got too analytical with us, had a Ph.D. in psychology that had been gathering dust for the past eighteen years, ever since I showed up, followed by Aaron. She kept active in it through volunteer services, but she’d been threatening to get back into the game full-time. After all, Aaron and I were adults now, at least on a trial basis.

There came a low rumble from the family room floor — Dad was waking up. He groaned, then stretched, and joints popped. Once on his feet, he looked at his watch. “Anybody in the mood for steaks?”

“Too late,” I said, clapping him on the shoulder. “We’ve voted on pizza.”

“Even better,” he said. “Anything but Italian sausage.” He grinned at Mom and she stuck her tongue out at him.

Dad grabbed me from behind in a bear hug that cleared me off the floor. He’d kept a strong build over the years. We were the same height, five nine, but I was a lot slighter. I used to wonder if it bothered him that I never followed in his footsteps as far as high school athletics were concerned. He’d been a pretty big deal, especially in football. But I realized it didn’t matter to him that I’d gone another route. When I went out for Little League one summer, he hadn’t pushed me into it. And when it turned out that I couldn’t hit the side of a barn with a ball or a bat, and couldn’t catch much better, he didn’t seem ashamed. He just set me on his knee and told me that sports weren’t everybody’s cup of tea, and someday I’d find something that suited me better. And then he hugged me. A kid can never feel totally at ease when he loves his father, because he wants to make his dad proud, but it was great to have some of the pressure taken off like that.

I kicked back with my heels until Dad let me down again, and while he and Mom debated various pizza toppings, I went to my room. Rainy-day boredom. I flipped through a book here, a magazine there, working my way to the right-angled shelves in a corner. I picked up a small ship-in-the-bottle display. It wasn’t your typical Cutty Sark, but a Viking longship. Dad had gotten it for me years back, after telling me we were of Scandinavian origin.

I guess I’d started burning with curiosity about who we were at about the time Roots came along. Happily, my grandmother Iris, Dad’s mother, was a storehouse of information. She had married a third cousin, and a common ancestor to both Grandma and Grandpa had, sometime around the turn of the century, traced the family back for centuries. He knew all about how the family had come down into Illinois from Wisconsin, and before that how we’d lived in eastern Canada and Newfoundland. He’d traced us all the way back to Iceland and Norway, as the descendants of genuine, hot-blooded Vikings. It’s not as impossible as it sounds. Vikings were often fanatical about keeping records of genealogies.

He’d even discovered the origins of our Anderson name, which was apparently different from all the other Andersons. Vikings, as I learned from my own reading into legend and lore, sometimes formed a surname based on their father’s first name. The son of Magnus, for example, would become Magnusson, and so on. Long, long ago, some man whose identity Grandma no longer remembered had had a father called Handorr, and thus the name Handorrsson was born. It stuck, for some unknown reason, and over the years became Anglicized into Anderson, now no different than the Anderson that originated as the son of Anders.

Every now and then, when feeling especially proud of my heritage, I was tempted to revert it back to the original spelling. But easier said than done. The name Chris Anderson was probably logged into ten thousand computers across the land, and were I to suddenly become Chris Handorrsson, I would probably find that I no longer existed.

No matter. The real pride was alive and well on the inside, where it counted. Knowing what I did gave me a sense of belonging, a sense of history, of being a continuation of history.

I put the ship back and sat by the window, much as Aaron had been doing. Aaron … he and I were something of an enigma to the Anderson family. These things tend to crop up more easily when you have such extensive family records. While there had been plenty of Anderson sisters, we were the first brothers to come along as far back as anyone could recall. Given this, and that I’d come first, and that I had the characteristic blond Anderson hair while Aaron’s was brown, you have the basis for a lot of older sibling torment. I used to tease Aaron mercilessly about knowing where he really came from, and that if he pissed me off once too often, I could send him back to that other place forever.

Ironic, then, that Aaron would probably amount to more in life than I would. My grades were by no means imbecile level, but his had always been better. And he could draw, too. Very well.

I remember when he’d first arrived at high school. Despite the difference in our hair color, we looked quite a bit alike, and no doubt his teachers were worried at first. They probably expected a junior version of me. After all, I’d been the one suspected of flushing a cherry bomb down the john. I’d been the one to TP every last bathroom, male and female, in honor of Halloween. I’d been the one to tape a giant Penthouse poster to the auditorium’s movie screen before it was unrolled to show a drivers ed film to the entire sophomore class.

But their fears proved needless. The model student, that was Aaron, the little yuppie-to-be. And it’s easy for me to picture all the teachers gathering in their smoke-clouded lounge, marveling at how he’d turned out so well, considering the influence he’d had from his older brother.

He was his own person. It would take a lot more than me to turn Aaron bad.

Chapter 4

The next couple of weeks passed quietly, the only event of note being that Phil and I started our jobs with the highway department. Our comrades in sweat were all real Americans: red necks, white T-shirts, and blue ribbon beer. But we got used to them quickly enough, because they really were a pretty nice bunch of guys, despite a certain crudeness. At first I feared they might resent Phil and me, college boys slumming for the summer. But most seemed to respect us for trying to make it beyond Mt. Vernon, and all of them jibed us endlessly about going after that college pussy.

A couple of days early on, the foreman, a fellow everyone called White Trash Joe, let us sneak off early, so we could have some fun on our summer break. Our workda

y usually lasted until three o’clock, but he let us go around one, and said they’d cover for us if the need arose. Phil and I hoped they’d make this a habit.

At the end of my first full week at work, I celebrated my eighteenth birthday. It really wasn’t until Saturday, but festivities began Friday night with Phil and Rick. Phil gave a solemn speech on how I was of legal adult age now, and if I screwed up, my own ass was on the line instead of Dad’s. Rick serenaded me, batting his eyes and flipping his long hair around while he strummed his guitar and sang Marilyn Monroe’s vamped-up version of “Happy Birthday.”

But I’d saved the best for Saturday night.

Her name was Valerie Waters, and she was the closest thing to a regular girlfriend I’d had in almost a year. We were still free to date others, and I know she had on a couple occasions. I hadn’t. No guts, I guess. No matter how much a guy has going for him, he still puts it all on the line when asking someone out for the first time.

We started out by going to dinner at one of the nicer places in town. Italian villa decor, wicker decanters, romantic music whose source remained a mystery. She paid for everything. “No one should ever have to spend money on his birthday,” she said, getting no arguments from me. Next she treated me to a movie.

Finally we were free from the constraints of dating protocol, and could get down to the business we thought paramount: discovering ourselves and each other, still taking our first clumsy, innocent steps down a road that alternately thrilled us and terrified us.

I drove us north out of town in my Chevy Malibu. Made the turnoff at seven miles. Drove us back into that recently discovered secret world that so readily accepted us and sheltered us from the outside.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

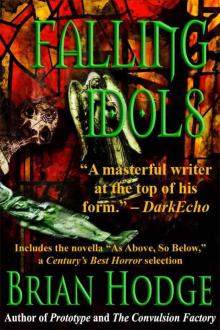

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols