- Home

- Brian Hodge

Deathgrip Page 31

Deathgrip Read online

Page 31

“So what brings you by here tonight?” He sincerely wanted to know, and the idea that others may yet have been lurking just out of sight had only now entered his mind. “Catching me in my finest hour here, this had to have been an afterthought.”

“I was down in the music studio.” She flipped a glossy fingernail along the hallway, then dug into a pocket for some hastily folded pages. She unfolded them, and he saw they were music staff paper, with handwritten notes and lyrics. “I was working on a song earlier, on the piano, and I got tired and stretched out on the floor. It’s peaceful here this time of night.” A cocked eyebrow toward his own audio arsenal. “Usually.”

He pointed at the pages. “Something you’ll be singing on the show?”

She shook her head. “Hardly. This is just for me, for now. I mean, I don’t have anything against gospel … but there’s a certain, um, sameness to it all.” She strolled closer, hitting from the mug again, and knelt long enough to peer into the cassette player window. “Iggy Pop, that’s what I thought. Obviously, you feel the same way.”

“A well-rounded listener is a healthy listener.” Sounded good, at least.

“I probably owe you one, since I caught you in mid-misgiving like this. My main musical heroine?” She exaggeratedly glanced over her shoulder at the door, beware of lurkers. “Patti Smith.”

He laughed, delighted. If Iggy Pop had been the New York scene’s godfather of punk, then Patti Smith had been its mother superior. This encounter was boding hope for his tenure at Dawson Ministries, perhaps not to be truncated quite as soon as he’d thought thirty minutes ago. “I would’ve bet no one around here had even heard of her.”

Laurel folded her arms around herself and rocked in bliss. “Mmmm. Anybody who can sound that passionate and insane and spiritual at the same time, they have my devotion.”

Paul had to wonder. How had he sounded ten minutes ago as she’d stood listening in the hall? Surely he had been firing on at least two of those three cylinders, maybe all of them.

Laurel frowned into her mug with bitter heartbreak. “This is cold and I hate it now. Would you want to come along while I go on a coffee run? There’s this place I like in the city, it serves cappuccino that could fuel a rocket. It keeps me going for hours, and I really want to work on this song later.”

Paul was already gathering his toys. “Can I get food there? I haven’t eaten since…” Just when had it been, anyway? “Forever.”

“Oh sure. If you don’t mind health food. The place is called Bran Central Station.”

He cocked his head in puzzlement while flicking off the lights, shutting the booth door. “Health food and caffeine?”

Laurel led the way along the hall, wired to the gills. Like she really needed another dosage. “Yeah, it does seem contradictory, doesn’t it? I like to think of it as a health food deli for hypocrites.” She laughed, quite the merciless tease. “You should fit right in.”

“The rebel thing again?”

She nodded, and oh, that hair, it was magnificent. “You’d better watch it, though. If you call yourself a rebel, it just defeats the whole purpose.”

“Don’t worry,” practically striding to keep up with her. He patted his chest, heart, soul. “Rebel without a clue.”

And she liked that one a lot, too.

Chapter 27

At first Donny was terrified to see Mandy go to sleep again. Lapse back into a regular cycle, so soon? Hadn’t she gotten her fill these past four months? He was apprehensive enough to eat his own fingernails; what if she kept on sleeping all over again? All of which was irrational in the extreme. Irv had tried to get him over this one too. A coma did not behave like the common cold — succumb to knockout, only to resurface in a mutated viral guise.

No, no relapse, he had to keep clinging to that promise. If faith could move mountains, then surely it could keep Mandy moving under her own power.

It was Friday, two days after her deliverance, and already she was in daily therapy. Irv Preston had promptly arranged for a physical therapist. First session yesterday, laying out an easy regimen for her first week of consciousness. She would sit up, she would stand, she would turn. None of which sounded like a tough order to fill.

Until you watched her try to accomplish it.

He’d watched with a potent mingling of admiration and anguish. Recuperation had sounded so pleasant and relaxed. It was, instead, harsh and loud and painful and sometimes ugly.

Her anger, her denial, her unconscious rage, all had come to full boil yesterday during the first session. No doubt accelerated by the unique way she’d emerged from the coma in the first place. That had to have made a difference, because it was so distinctly unnatural.

Paul. Miracle worker, content to operate behind the scenes, just their little secret. Who did as asked, without complaint, and this made his outburst two nights ago all the more surprising. A harsh tongue in that man’s mouth. Although, quite possibly, bringing Amanda back from near death may have entailed a greater emotional impact than he was accustomed to. This had been no run-of-the-mill healing. This time it had mattered on a personal level, a ministry level. And bore with it a new twist: an aftermath that would have to stick around and witness.

And … admittedly, he had been a bit rough on Paul immediately afterward, in that first malignant moment when results hadn’t been up to par with hopes. He would have to remember to make it up to him, and soon. But it wasn’t like he didn’t care about Paul’s happiness, and deeply. He had given him the radio show production to keep him busy. And was going to great pains to keep Paul from finding out that, in reality, the tapes were not actually being used. Instead of being used for radio syndication, they were collecting dust in a locked cabinet. Radio time would be a wasted investment at their level of the game.

White lies were excusable, when happiness was at stake.

Paul would keep, he would be fine. For now, Donny’s sole attention was on Amanda. Her efforts and struggles, sorrows and frustrations. All of which were on display at the moment as she sat upright in bed, propped against a barricade of pillows like an egg in a carton. A contraption called a Bobath splint — like a thick rectangular pad wedged into her armpit and a couple straps with Velcro fasteners — held her right shoulder in place. With a left-brain injury, she would need the majority of attention focused on the right side of her body, given the crossover of most nerve functions.

Donny dragged a chair beside her bed, sat with elbows on knees, hands steepled beneath his chin. Love had been renewed, somehow, that fresh excitement of getting to know her all over again. He would strive to avoid the same mistakes this go-around. He would listen more.

“There’s been so much I’ve wanted to say to you the past couple of days. Wednesday night, yesterday.” He reached out to hold her right hand, in its splint. Her left remained on the bed as she regarded him with eyes that looked huge within the winnowed-down sculpture of her face. “But it never seemed right. You were in so much pain.”

Mandy nodded, her head a tremendous weight to be supported by that fragile stalk of neck. “Mmm hmm.” She was getting by, as much as possible, with phrases like that. Her speech, assuming it came back on its own, would take about another week. For now, it was characterized by the round, muted texture often heard in a deaf person who had recently learned to talk. The sharp angles of pronunciation blunted by lack of practice and the odd cranial mishap or two. Like, when she said what, it was came out sounding like wad.

“I’ve missed you, I can’t tell you how much.” He didn’t mean to cry, but there it was, the tremble of his lip and the rapture of brimming eyes. “I’d come in and talk to you every day. And when I couldn’t be here, I had the nurses play tapes I made for you. Do you remember any of that? Irv says that even inside a coma, people sometimes hear what’s going on around them.”

Mandy’s gaze lowered to her lap, and she looked up again with a crisp nod. “I … tink so,” spoken slowly, with great care and concentration, striving fo

r normality. “I ‘member your voice. Close to my ear.” Her eyes darkened then, looking not at him, but off to one side. “Know what else I ‘member?”

When she looked at him again and he saw just how truly harsh that stare was, his heart clutched. The tears felt to drain back into his skull, where they would burn, corrosive.

“I ‘member…” Her eyes closed, and she rattled a fist in defiance of thwarted effort. A word was eluding her — expressive aphasia, the therapist had called it. “Shit!” she cried, and Donny winced.

That was another thing he’d been warned about. Typically, coma patients woke up behaving like children who’d had too little discipline. Gratification was a concern of the great and mighty now, and there were no inhibitions. They might say things no one would ever have suspected of crossing their minds at all. Saintly little old women, exploding into fits of language that would make a longshoreman blush. Kindly old men, spewing lecherous propositions to any nurse in earshot. Couple that with the likelihood of emotional lability — severe instability and inappropriateness — and they were all geared up for more than their fair share of uncomfortable moments.

He had hoped she would prove an exception.

“Falling!” Amanda shouted, following with a triumphant, “Hah!” Savage ecstasy on her face, she’d pulled it from memory, and what was he supposed to do, toss her a treat for reward? Then, just as suddenly, her face grew sullen again. “I ‘member falling. An’ fighting. Why we were fighting.”

Of all the things she’d left inside herself, why couldn’t that have been one of them? Dear God, why couldn’t You have blotted that from her memory?

Tired of living out lies, wasn’t that her phrase for it? Sure it was, famous last words for nearly four months. He’d replayed them thousands of times over in his head.

“But so much has changed since then.” He was pleading with his hands. “So much has happened with the ministry.”

“But I haven’t changed my mind. It’s still … yesterday … to me. An’ I don’t tink it’s right anymore.” She frowned at the way the words lurched out. Especially those last two, sounding like wight anymwah. Her frown curled into a brittle frightmask of self-loathing, and she burst into fresh tears, and couldn’t they give her sedatives? “Oh hell, I hate the way I sound! Hate it hate it hate it!”

Donny possessed options aplenty. He could laugh, he could cry tears of grief, he could run screaming from this room and try setting foot in it later. Or he could sit in numb distress over the realization that she was a complete stranger to him, not the same woman he’d been married to in early June. How dare she change on him while she was in there.

The self-loathing proved contagious, for none of these were the impulses of a strong and loving husband, and perhaps worst of all was his sudden second realization: Maybe he wasn’t the same man who had proposed to her. Change being a two-way street and all.

He dove in, salvage something, anything, leap into this fray, so he wouldn’t have to deal with himself. “Mandy, listen, listen to me. Let’s stick together through this thing, I promise you we’ll get through it and you’ll be yourself again, I just know it…”

Rambling, on and on and on, years of expertise in pulpit motormouth, with none of the eloquence. He leaned forward to hold her. She struggled against his touch at first, then succumbed and fell still within his arms, frail shoulders twitching with the occasional sob. It was like holding a captive bird, and still he rambled on. No idea as to who he was trying to convince of this fantasyland happily ever after.

“There’s something you need to know,” he said after a few moments of calm embrace. “I know you were having some problems with … with the ethics of what we were doing. But it’s for real now. We’ve healed so many in the past few weeks, we’ve lost track, and do you know why?”

With her face buried against his shoulder, now damp, she shook her head.

“Because I’ve met a young man who can do it, really do it. Every time out. Do you think the Lord would’ve led him to me if he wasn’t supposed to be here?”

Amanda pulled back, eyes widening in surprise. Wariness?

“He’s the one that brought you out of your coma. You saw him there with me when you first woke up. He restored you.”

Settling back against her pillows, she tilted her head at him, quizzical. Red eyes and damp cheeks were the only evidence of distress now. She had forgotten to cry.

“He’s from St. Louis,” and Donny was already feeling that warm glow rekindled, everything would be fine. Paul healing by the mere thought of him alone. “He’s been such a blessing.”

Mandy sat up, blinking, owlish. “I thought that was a dream … something.” Nodding to herself. “I ‘member him.” Then back to Donny, nailing him with another crucifying gaze. “What are you doing with him here?”

Donny cocked his head. “What do you mean? He works for us.”

She beat on the mattress with a loose fist, shook her head with a heavy sigh. “I mean whose idea was it?”

Donny turned palms up, innocent, nothing to hide here. “I suggested it, but only after he came looking for me. For guidance. He’d had some severe personal problems with it.” Better for now to withhold what those problems had been, and when he got no reaction, Donny plowed ahead. Anything was better than the torturous silence between them. “It’s important you be careful what you say to him, I need to warn you about that. He thinks you came down with a fever while doing missions work in El Salvador, that’s what, ummm, everybody believes, almost, except for Gabe, and Irv, and the nurses, and … and…”

And Donny had sufficient presence of mind to shut his run-on mouth before this got any worse. In fact, he should have shut it long ago, as he now found himself sucking on both feet at once, while a brand-new front of anger was storming into view across Amanda’s face. Awesome to behold, Shouldn’t have told her this, I really shouldn’t have … but I thought she’d have wanted us to do it that way—

“You lied to everybody we care about?”

—for the sake of the ministry—

“You LIED?”

—for the sake of our lives—

“You hid me away here the whole time with a — a — a cover story?”

—but—

“You were ASHAMED OF ME?”

—she’s not the same now as she was then.

“You’re STILL ashamed of me, aren’t you? Aren’t you? That’s why you want to have all the therapy equipmen’ built into that other room!” Amanda’s eyes, flaring wildly, huge and glazed with intensity. Accusation. Tiny droplets of spittle flew from her mouth, and moments after she finished shouting, she exploded into rich laughter. “Hide and seek! I been the best hider of all, huh?” She laughed herself hoarse, laughed until she was crying again.

His existence had once been so ordered, so meaningful, and for the life of him, Donny couldn’t recall precisely when and where the slippage had begun. Now there was only damage assessment. The map-room charting all the familiar territory of their relationship had just been leveled to rubble, taken out by a direct hit. A cruise missile, fired from the top of the stairs.

He reached for her, to caress that quivering shoulder, She figured it out, a dull monotone thought, only she didn’t figure it the same way I did.

Reaching…

Contact.

She reacted as if he had jabbed her with a hot iron, jerking up and twisting from his touch. She swung a wild and oddly clenched left fist and managed to tag him solidly on the shoulder. He rocked back, more from surprise than impact.

“Don’ you touch me! Don’. You. Touch me.” Her breath came in hoarse gulps, long limp hair spilling darkly across her face. She made a couple of spastic attempts to push it back. A smear of snot glistened under one nostril, and for all the afflictions, Amanda was somehow exhibiting more — to put it crudely and in sexist terms — balls than he had ever seen. The demure peacekeeper, the gentle helpmate … gone, buried beneath a crumbled wall of inhibitions.

He had to wonder: Could that wall ever be rebuilt? Or was the damage too extensive, eternal? And speaking of eternity, how much of their future had been wrecked, as well?

To hold her, to draw together in a fortified stand, these suddenly seemed dead ideals. More than a decade past, when the ministry was just a stumbling patchwork dream and nights were sometimes spent hungry, they could hold each other and generate more strength and hope together than was the sum of their parts. God had seemed to smile upon them then, even through clouds and rain.

A lifetime or two ago.

Anger and energy spent, Amanda slumped into the bed, the pillows. Nightgown twisted, though she didn’t notice, or care. She resembled a carelessly dressed, heedlessly flung toy. The Amazing Mandy Doll. She sleeps, and sleeps, and sleeps — and just when you think things are going smoothly again, she awakens into a cranky stranger.

She rolled her head up to stare at him instead of into her lap. A softer gaze now, a most welcome change, oh thank you, thank you.

“Donny? What have we done to ourselves here? What have we done?”

No ready answers, only the sound of his heart ripping loose.

Love is a many-splintered thing.

Chapter 28

Love had its peculiar mercies, and if this wasn’t yet love, it was at least a case of the mutual irresistibles. Paul felt comfortable with it happening, hence the mercy: If you’d been through it once, you were already broken in, because all relationships left the starting gate the same way. Regardless of where they were headed.

Finding out where, now that was the fun and scary part.

Bran Central Station was the arena in which it got its start, and Paul liked the place just fine. Down a flight of stairs from street level, follow the wrought-iron rail. The tables were a fifty-fifty split between round and square, never rectangular, always tiny, always intimate. Large groups need not apply. Walls of aged brick, low-raftered ceiling of oaken timbers, and the Elysian aroma of a whole-bean roast coffee market. Laurel pointed out the minuscule stage at one end their first night there, told him that folk singers sometimes played from tall stools. Ambient tapes played the rest of the time, everything from vintage sixties to digitally recorded whales. Old hippies would come here to die.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

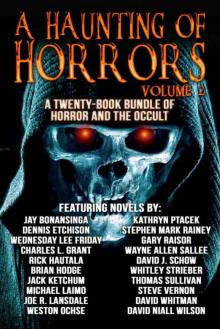

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

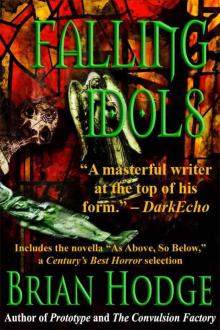

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols