- Home

- Brian Hodge

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Page 4

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Read online

Page 4

Most of what I could find on Cameron, however, was related in some way to his involvement with a group known as the Starry Road. They seemed to go back for many decades, possibly as early as the 1920s, but there was no official information on them anywhere. They had no online presence of their own. There was only what other people said about them, as well as the rare instances when people claiming to be one of them briefly turtled their heads aboveground. What little there was, predictably, was a tangle of contradictions, speculation, and invective. References made the Starry Road sound as if it could be anything from a cult to a tribe of New Age sky-watchers to a consortium of academic washouts. One frothing diatribe, purportedly from a relative of an alleged member, deceased, accused them of being worse than the doomsday group who’d triggered the sarin gas attack in the Tokyo subway, although the rant was so rife with misspellings and erratic use of capital letters that I found it hard to take it seriously.

What seized me hardest, though, was a seemingly offhand comment from a fellow member referring to Cameron as “the scion of our sainted Helen Lytner.”

Our mother was considered sainted? Ironically, this was in no way related to her years as a Catholic novitiate. It was my first indication that she’d ever done anything more than shut me out, warp my brother, and make terrible choices in men.

When had she found the time, for one thing?

In the end, and well past the hour I’d promised Ashleigh, I felt scarcely any closer to unraveling who or what my brother really was. On one level, we had more in common than I ever would’ve guessed, something that was supposed to be mine alone. He’d just carried it down a stranger path.

Before going to bed, I clipped Isis to her leash and took her out along the verge for one last squirt of the night, and a time-out to wrap my head around what to do.

The prospect of later employment, however remote, wasn’t an insignificant consideration. The future of space really did lie in the private sector. I’d followed my bliss, and sometimes I worried.

For any kid who’d dreamed of going to Mars, as the next great frontier, nothing could be more demoralizing than growing up to learn that our original rush into space was entirely a by-product of post–World War Two victory spoils and Cold War agendas. We’d welcomed a group of German defectors who were leaps ahead of our homegrown scientists in rocketry. Then the Russians got serious about the skies, and we freaked: What if they weaponize space? The Mercury missions, the Apollo program, the moon landings…discovery and exploration were incidental. Underneath, it was all about beating the Soviets. Mission accomplished. And now? Now every motivating factor we had is dead in the dust of a bygone age, with matters like NASA funding in the hands of the kind of shortsighted electable idiots who proudly campaign to their knuckle-dragging base on science being lies from the pits of hell. Now it seems our imagination hits a ceiling at Low Earth Orbit.

It was just a daytrip to Portland.

But maybe I should’ve listened to Isis. She walked tentatively, as if I might be leading her into a trap, and more than once grew perfectly still, one paw raised as she stared down the street past my shoulder, as if, many blocks away, there was something only she could hear.

* * *

I drove.

In coming up from Portland, Cameron had left his car at home because he’d wanted distraction-free time to mull over how best to reach out to me, and had taken the bus. So he claimed. Although if you were to put Cameron in a lineup with any four other random guys and ask me who looked like the type to ride BoltBus, I guarantee I would’ve ranked my brother dead last.

In theory, a ride through chilly autumn drizzle would have given two long-lost relatives time to reintroduce themselves. But it was clear to me that he’d already known a lot about me before he ever got to Seattle, and Cameron was smart enough to assume I would’ve since tried the same.

“Tell me I’m wrong,” he said. “You fed me into Google last night.”

“Which you probably knew I was going to do even before I knew.”

“And in spite of what came up, you’ve decided to take me seriously enough to go anyway.”

“You said the right things to get me interested. And it’s just a few hours. We’ve practically been neighbors for a while.” I peered at him, letting the metronomic thump of the windshield wipers keep time for a few moments. “Portland? Really? You get around, or used to. You just happened to end up in the next major city south of me?”

To his credit, Cameron didn’t expect me to swallow a coincidence. “Nobody just happens to do anything. Is it that out of the question that I might get to a point where I wanted to be near you, if not necessarily crowding you on your own turf? Especially since it turns out we have some overlap in our interests?”

“What I’m interested in is science. Legitimate research and hard data. I don’t know what to call whatever it is you’re interested in.”

He seemed to not take this personally. And it went more easily after that. We could squabble with impunity. Almost like…well, brothers.

By his own admission, he’d spent the years since I’d last seen him feeling entitled to take whatever he wanted, whenever and wherever he wanted it, and he’d apparently been very good at this. But if under most circumstances someone who’d been indulged the way Cameron had been would’ve grown up to be a petty criminal, or maybe an exceptional criminal, destined for a devastating reawakening in prison, this was not to be my brother’s path.

Simple thievery betrays such a failure of the imagination. Theft is a trade, really, one that works with tools, and one look at Cameron, then and now, would tell you that this was not someone who considered himself a craftsman. Presumably he could’ve gone to Wall Street and achieved even greater ends, legally, or if not, with much less chance of getting caught, but he wasn’t wired that way, either.

This was not how our mother had raised him.

Instead, knowing full well that I’d found what a search engine had to say about him, Cameron described himself, circumspectly, as something between a spiritual teacher and investigator. While that was what came out of his mouth, what I really heard was charlatan, maybe cult leader. I was reminded of a story, possibly apocryphal, I’d heard as a science-fiction geek in my teens: that Scientology had gotten its start not long after its founder, L. Ron Hubbard, told an informal gathering of fellow 1950s s-f authors that he was going into religion, because that’s where the real money was.

“So what is it you do?” I asked. “The Starry Road, whatever that is. I mean, what is it you offer that the big ones can’t provide?”

“The truth,” he said. “What else is there?”

Of course. Everybody was after a monopoly on the truth.

Except whatever he knew, or thought he did, Cameron didn’t sound happy about it. The closer we got to Portland, the more uncomfortable he seemed to find the car seat, and the longer he spent staring intently out the windows, lingering on the ephemeral patterns made by the thick, dark scum of clouds. Although by the time we crossed the Columbia, he seemed over the worst of it, back to his semi-smug self again.

“By the way,” he said. “You really should give your neighbor Lara a try. Take things up to the next level or two. She was…fun.”

“What do you mean, fun?” I didn’t like the way he’d said it.

He snickered as if I’d asked something beyond obvious. “What do you think?”

“I think you’re an asshole.”

“Two consenting adults. You’ve got no room to complain,” he said. “Besides, you left me all alone there, with nothing to do. The way I read it, you were giving me tacit approval to go back downstairs.”

But it was all an act, I was starting to decide: this self-satisfied air that he tried to effect. It was a cover, a mask. He wasn’t particularly happy with himself.

Or maybe I just needed to believe this to convince myself, now that I’d made his reacquaintance, that I really had been the lucky one.

I couldn’t help bu

t contrast Cameron with the subject of the article that Ashleigh had hung on her refrigerator the day before, and wanted to be sure that I saw. Reason of the Day, she called this habit. Nearly every day she would look for some reason not to despair of where the human race was headed, an antidote to both the depressing levels of species dysfunction that comprised most news, and the evidence she saw right in front of her every time she went to work. Big reasons, small reasons, any reason. When she found one that resonated, she’d clip it or run a printout or jot it onto a notepad, and tape it to her refrigerator.

The latest one? It was about a cancer researcher who had developed a new test to detect pancreatic cancer—that again—not only earlier, but with a method that was 168 times faster, 26,000 times cheaper, and 400 times more sensitive. He was a fifteen-year-old high school freshman, and this was his project for an international science fair.

I loved this kid. This was somebody I wanted to be related to. What might Cameron have done, I wondered, if he’d channeled what appeared to be his considerable personal resources into something like that, instead?

Yet here I was, indulging the crack in that 99% certainty I had that this trip would amount to nothing, because that 1% what-if wouldn’t leave me alone.

* * *

The destination Cameron directed me to sat just outside the fringes of the Pearl District, a zone spreading west of the Willamette and north of downtown that had first risen up as an industrialized landscape of warehouses, railroad yards, and small factories. The blue-collars who’d built it would hardly recognize it now. As the new millennium approached, it had all started turning to condos and lofts, galleries and boutiques, and everything else you’d expect to spring up around them.

Cameron’s building, though—whoever owned it—had missed this renaissance of urban renewal. It stood alone, two tall stories of vintage brick, still living in the old world, along with everything else around it, the whole block shabby and nondescript. An ideal place, actually, for hiding in plain sight.

As we rolled past the front, to my eye it looked unused, and uninviting for any decent purposes. It might have been charming once, decades ago, in a Depression-era drugstore and soda shop kind of way. But now there was nothing to identify it, just a metal sign bolted to the brick: NO TRESPASSING – PRIVATE PROPERTY – VIOLATORS SUBJECT TO ARREST. A bank of windows spanned half the front, but there was no looking through them, or breaking through, either. They were covered with rusty iron mesh on the outside, and tightly drawn blinds inside. A widely spaced trio of arched windows ran across the upper floor, with heavy curtains pulled shut inside.

I found it simultaneously underwhelming and ominous. Anything could go on in a place like this, and no one might ever know, as long as the noise stayed below a certain threshold.

“Don’t tell me,” I said, mostly to break my own unwelcome mood. “Everything happens in a network of underground labs and bunkers, right?”

“Keep going to the end of the block,” Cameron said. “I usually go in through the back.”

I kept reminding myself of what he’d said that piqued my interest in the first place, even if was against my own better judgment…

How about something a little more interesting. More definitive. How about a subject like…what would you call it…astrobiology?

What branch?

Kind of a cross between the two.

The view from the alley was more of the same, except worse, because we passed people back here. Cameron looked at them with mild surprise and stronger disgust, as if he’d never seen them before, and it wasn’t an act—even at first glance I didn’t think they had anything to do with him. It was just this place. For decades, Portland has had a reputation as a heroin mecca, and that was my guess here. At least five of them, lost souls all, were tucked into doorways, between dumpsters and walls. They watched us pass with lethargic interest, as if they were here but didn’t know why, and maybe now that we were here too, they’d find out.

A glimpse, then gone: One of them appeared to have a lower leg that was down to dull white bone, tibia and fibula jutting from a ragged pant leg. A moment later we were past, and already I was doubting I’d seen what I thought I had. He had sticks—fragments of a crutch, drumsticks—and the mind loves to impose order.

Like grouping stars into constellations.

When I stopped the car, it was just the sound of the rain on the roof, and for no reason I could put my finger on, everything felt wrong. No rational reason other than the vibe my brother was giving off, as if he would’ve been content to ride forever rather than actually arrive.

“What is it you’ve got going on here, really?” I asked.

“I, uh…I got in over my head with something.” He sounded mystified as to how such a thing could even have happened. “It’s not that I expect you to do anything about that. But I thought you might have connections. You know…a professor who knows somebody who knows somebody else who might be qualified to deal with this.”

“Deal with what?”

“You really just have to see.”

“You couldn’t have just brought a picture?”

That earned a sardonic snort. “You ever notice how all those annoying pseudo sophisticates online are always calling fake on everything? Even when it’s not all that unusual? Like someone with really cut abs? Just because they think it’s easier to explain something away with Photoshop rather than consider it might actually be real? Yeah. That was the kind of reception I was imagining a picture would get.” He shook his head. “It’s not just enough to see. You have to believe me, too.”

He slammed his way out of the car.

I really did consider driving off then. Do that, though, and I knew that I would always be plagued by the worst kind of wondering. If there was something amazing here, I would always wonder what I could’ve gotten in on. If it went badly for him, I would wonder how I might’ve helped. And if I never heard anything more…

Well, that would be the most corrosive frustration of all.

I locked the car behind me.

The rear of the building lay beyond a miniature courtyard, surrounded by a high wooden fence that didn’t appear weathered enough to have been standing for more than a few changes of season. The outside of it was further protected by a wraparound layer of chain link fencing, then topped with five strands of barbed wire. Over in one corner, tatters of…something…trailed from several barbs.

They seriously wanted to keep people out here. Were the junkies really that bad? I supposed they could be.

Cameron let us in through a heavy-duty door in the fence.

“She may have made her mistakes. She may not even have been conventionally sane,” he said. “But our mother was tapped into something.”

I felt everything tighten. So what if she was. It excused nothing.

He fumbled with his keys at the building’s steel back door. “You must know that Arthur C. Clarke quotation about technology and magic. Don’t you?”

I did: Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

“Well,” he said, and had to steady one hand with the other to get the key in the lock. “There’s at least one good variation of it that was waiting to be coined. Any sufficiently advanced intelligence is indistinguishable from godhood.”

He got the door open.

“I, uh…I really thought we had something here. And we do…”

We were in a back room—an old stockroom, maybe—dim, almost bare, walls whose paint had finished peeling decades ago. With another door waiting ahead, Cameron’s voice was beginning to show some serious strain.

“But there’s something wrong with it.”

Before I could even begin to fathom what that might mean, we were at the second door. Cameron knocked, to no response.

“You have no idea what it’s been like.” He was whispering now. “How can you? For two years now, it’s hardly given me any peace. You’d think something like this would have autonomy, but it doesn�

��t. Everything, it depends on me for everything…belief, devotion, love…I’m the one who has to deliver it all. And it’s draining the life out of me.”

Then he got this inner door open, too.

“She told me I was born to rule, and instead I’m its slave.”

And then we walked into a charnel house.

When something goes unexpectedly, horribly wrong, people on average have a four-second lag time while they process the information. Until then, they quite literally can’t believe what’s happening. It’s easy for people to get hurt or get killed during these four seconds, because they haven’t yet figured out what to do. I learned this as an undergrad, at a standing-room-only lecture on the psychology of campus shootings.

But even after four seconds, thirty, a minute, I was still there. Still processing.

Blood…I could’ve processed that. But there was remarkably little, considering. Evidence of hacking, shooting, stabbing, beheading…I would have known what this meant. I would’ve known whether they were fresh or not. I would’ve known whether there was a reasonable chance the killer was still in the building. I would have known to run.

Instead, I didn’t even comprehend right away that there had been anything deliberate about this. What was laid out so haphazardly in front of us might well have been the result of an industrial accident. Most of the bodies—easily more than a dozen, maybe upwards of twenty—looked charred and blackened, skin split like sausage casings. The worst appeared to be rough likenesses of human beings sculpted out of carbon.

Lightning, I thought, groping for an explanation that could make sense to me. Ball lightning. A mass suicide conducted with an electrical main. A plasma weapon from a science-fiction story, which couldn’t happen anyway, because the world was still waiting for someone to solve the portability issue.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

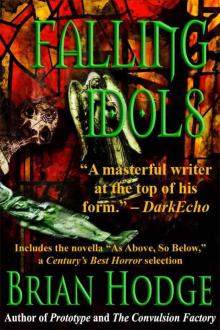

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols