- Home

- Brian Hodge

Picking the Bones Page 5

Picking the Bones Read online

Page 5

So now I keep wondering what would’ve happened if I hadn’t awakened the other night, if I’d remained asleep and so had you, without me to serenade and reassure you, knowing what you were dreaming in there: the noise and the compression, squeezed before your time…like garbage in a truck. In such a dark place, experiencing the first dreams you’ve ever had, how could you possibly distinguish between what’s real and what isn’t?

And from all the way out here, how can I possibly protect you every moment?

*

No school today. For me, that is. For everyone else it’s education as usual.

I did get halfway there. Walking, like normal. I’ve always maintained it’s good for us…me and my Tadpole, out for a stroll. Ever since the jumper, though, I’ve been detouring from the usual route. My mistake. Keep going by the bell towers, and all I would have had to contend with is a daily reminder of what that poor girl did in front of me.

The block I was in is kind of run-down, but then, close to home, they all are. It’s just that this one wears its age in a more picturesque way. There’s a deli that’s been in the same family for four generations, and a flower shop run by a woman old enough to have diapered at least three of those generations from the deli. I wasn’t even there yet, just crossing the street, when I started to hear someone crying. I wasn’t quite sure where it was coming from, just that it was getting louder, and seeming to echo off the bricks.

Before I saw even saw her, I knew where she must’ve been, because by then a little crowd had gathered, so as I came up, I was thinking, “Well, surely somebody’s with her, somebody must be taking care of this…”

Except nobody was.

She sat at the bottom of a stairwell leading up to some second-floor apartments, half-in and half-out of the doorway, one leg tucked underneath her as she sat beneath a row of mailboxes, one hand hanging onto the doorknob. And the other…

The main thing I remember is the bright red stain seeping through the yellow fabric bunched around her waist.

Somebody pointed and laughed, I recall that much. Everyone else, once they had the idea, they went on their way. Conversations resumed, footsteps quickened to be away from her. I wanted to help, I really did, and I know that I would have if she could’ve just shut up for a minute, but instead she kept crying, and crying, and…

I didn’t want you exposed to it, I guess. So I did an about-face, turning around to go home. I looked over my shoulder once, at the end of the block, and could see her arm still reaching out of the doorway.

All in all, not one of my prouder moments.

So it’s just you and me today. Maybe all the rest of this week. The way I feel right now, maybe until after you’re born.

The thing that gets me, though, is that no matter how hard I try, when I think back to that final glance I had of the woman in the doorway, with just her arm visible, I can’t quite remember if she was still beckoning for help…or pointing. At us.

Which probably wouldn’t be a big deal at all, if it weren’t for that stupid dream I had last night, about you whispering something in your brother’s ear. Just before…well, you know.

That’s just me being silly, right? First-time pregnancy jitters and everything?

All I want is to keep clinging to the same reassuring hopes that every woman has for her baby: That you can be anything you want to be. That instead of being forced to bend to the world’s will, you can make it bend to yours. That you can plant your ideas like seeds, and they’ll take root and spread like wildfire. That you’ll discover your own way to make things better.

Except right now I can’t help but wonder: Have you started that already?

Come on, Tadpole…tell me I’m just being neurotic. Because the more I think about this morning, the clearer it seems to me that the woman in the doorway really was pointing at us. In accusation. I mean, for a moment there, I saw her eyes. But why would she do that? What did we ever do to her?

So come on, Tadpole. Tell me I’m just stressed out. That you didn’t talk your brother into letting go. Not with a whisper, but with a dream.

Tell me that if I check with the doctors and demand to know, they won’t inform me he wasn’t merely one of the first to be lost…but the first. That you haven’t dreamed a dream so dreadful it echoes on and on.

Tell me nothing went wrong in there. I only want you to be normal.

Tell me, please…

Okay, all this is destined for the black marker. But I feel so much better getting it off my chest.

Remember our Einstein: “There are only two ways to live your life: as though nothing is a miracle, or as though everything is a miracle.”

To me, in this world, every day that you and I have together is a miracle. When you’re born, I promise to celebrate you as one. No matter what.

Until then, I promise to keep serenading you, to tell you how much you’re loved and that everything will be all right…or I’ll try to, at least. Lately there seems to be something terribly wrong, either with my playing or with my instruments. I never knew they could make these kinds of ghastly noises.

But you seem to like it anyway.

It perks you right up, and you dance again until I’m sick.

THE PASSION OF THE BEAST

From Entertainment Weekly, April 18—24 issue:

They said it was the movie that could never be filmed.

Then they said it was the movie that could never be distributed.

Now all they can do is call it the movie that shouldn’t be seen. By anyone.

They, of course, are the millions who have mobilized to contest the film that purports to be the story of the last twenty-four hours in the life of Jesus of Nazareth…a familiar enough concept, only this time shown from the devil’s point of view. It should surprise no one that they, more often than not, were among the most vocal supporters of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, a far more conventional interpretation of the same story.

The anticipation and release of Gibson’s film hasn’t been so long ago that anyone is likely to forget the firestorm of controversy that accompanied it nearly every step of the way. But in comparison, that was mere warm-up. As ardently as advocates of the original Passion rallied behind what they regarded as Gibson’s sincere profession of faith, over the past months their fervor has only amplified in opposition to what some of their tracts have called “the most poisonous blasphemy that any filmmaker has ever tried to ram down the world’s throat.”

There’s one big difference between this new film and its predecessor: In the public debate over The Passion of the Christ, the opposing sides were roughly even. For every pro-Gibson spokesperson who experienced his film as a shot of spiritual adrenaline—the next best thing to being there—someone else across the aisle was raising questions about anti-Semitism, historical accuracy, or simply thought Gibson had directed history’s most expensive sadomasochistic porn film.

Not so, when it comes to The Passion of the Beast. The debate is so lopsided that it can hardly be called a debate at all. You’re more likely to find advocates of terrorist pedophiles than you are to find someone of note who wants to go on record as encouraging people to see this movie. Those who are willing do their cause célèbre few favors: heavy metal Satanists, dour black-clad misanthropes with Charlie Manson eyes, and freelance loudmouths who would endorse their own executions as long as it meant a five-second soundbite on TV.

But someone out there must be in favor of keeping the projector rolling for The Passion of the Beast. The independent distribution deal with Riverwalk Films has the movie opening on more than 1400 screens nationwide.

So it’s worth recalling what Hollywood agent John Lesher was quoted as saying in a New York Times article on the eve of the original Passion’s release, before it grossed over $600 million worldwide, and while prognosticators were still using “Mel Gibson” and “career suicide” in the same sentence. At the time, more than one huffy, offended producer claimed he would be unlikely to work wit

h Gibson ever again, which Lesher dismissed as sentiments that would evaporate soon after The Passion of the Christ turned a profit: “People here will work with the Antichrist if he'll put butts in seats.”

*

Ardmore, Kansas. Opening day.

This may be the heart of the heart of the country, but the scene here is playing out in one form or another from coast to coast.

With a population hovering around 12,000, and about as far from one ocean as the other, Ardmore is the kind of place you picture when you hear the term “flyover country.” Or at least you get the feeling that’s the way its residents suspect they’re dismissed by the snobs and philistines on the coasts. You also get the feeling they don’t much care.

Ardmore is one of those places that exude a palpable sense that time hasn’t passed as quickly there as it has almost everywhere else. From its water towers and ball fields to its plain white steeples and corner stores, yesterdays hang over the town like a gritty brown cloud from the dustbowl days of the Great Depression. In the surrounding county, and the counties beyond, grain silos stand watch, and in a few months the low flat fields will become undulating seas of wheat.

And today’s the day the devil comes to Ardmore.

They’re ready for him. You get the feeling they’ve been ready for a long time. The protest crowd has been gathering near the theater since before dawn, and two hours before the first matinee it’s hundreds strong. Weeks ago, an ad hoc committee tried and failed to ban The Passion of the Beast within city limits. They may have lost the battle but the war continues. As armies go, theirs is peaceful, if you don’t count the cacophony of two different hymns sung simultaneously, started by rival songleaders at opposite ends of the crowd.

Ardmore has two theaters, five screens. Here at the Bijou—yes, some places still have a Bijou—the cinematic legacy extends back to the Jazz Age, although it hasn’t quite been left intact. Twenty-odd years ago, the epic screen that had once contained (barely) the likes of Lawrence Of Arabia was split down the middle, the center seats sprouted a drab wall, and that sacred cavern was halved, diminished. Instead of double features, the marquee exhibits a true split personality…

Bijou 1: Happy Gilmore 2

Bijou 2: The Passion of the Beast

It’s a reasonable assumption that Adam Sandler fans will be staying home in droves today. Would they really want to brave the gauntlet of picket signs, pamphlets, and megaphones, just to have their fellow townsfolk suspect them of slinking down the forbidden aisle?

With stoppage having failed, embarrassment is now the weapon of choice, as groups arrive by the carload and church busful to shame their neighbors into not attending.

“We’re committed. We’re here for the duration,” says Pam Landry. She’s a pretty blond woman, a mother of two, whose eyes gleam as she lifts the Samsung camcorder strapped to her right hand. “However long this filth plagues our town, we’ll be rotating in shifts to document everyone who supports it with their ticket money. There will be a reckoning.”

But there’s only one box office, one entrance. What of the innocents who just want to enjoy the continuing saga of a golf pro with lousy anger management skills?

Mrs. Landry appears to weigh the wisdom of admitting what she’s about to divulge, but can’t resist: “We have people on the inside, too. Lists will be compared. Mistakes won’t be made.”

Such tactics, or the prospect alone, will work on some—this is small-town America, after all. Then again, this is no village in seventeenth-century New England. Ardmore is large enough to have at least a little diversity of mindset and some exercise of free will.

The dissenters gather far on the other side of a row of barricades, the line in the asphalt drawn by Ardmore’s Chief of Police, who is in the unenviable position of having to balance the will of a clear majority against the rights of whatever minority dares to show up. His mandate is enforced by a pair of patrolmen who already look bored as they lean against the fenders of their car. They’re here to prevent a riot, and instead they’re presiding over a sprawling prayer vigil.

With an hour to go before the first matinee, prayers don’t appear to have changed any minds. Those intent on seeing the film number just over a dozen thus far, so it isn’t difficult to do a head count, and they stubbornly hold their ground. They’ve shown up early not because they feared a rush on ticket sales, but because the street theater promises additional entertainment. At the Bijou, it’s two-for-one day.

They don’t look evil, or even dangerous. They’re young, students or recent graduates, skipping school or off work or still looking for that first real job in a town where opportunity doesn’t knock very often.

Joey Taggart has decided to use the occasion to make an editorial comment of his own. He says he’s eighteen but looks younger, with the lank hair and decade-and-a-half-out-of-date torn jeans of a kid who’s only just now discovered Kurt Cobain. He can’t stop grinning, eager to poke back at his hometown’s rank-and-file by wearing a garment emblazoned with Ardmore’s logo and embellished with the line: My future went to Hell and all I got was this lousy T-shirt.

“What’s the big deal, anyway?” he says, eyeing the legions that have shown up in a last-ditch effort to make him rethink his plans for the day. “They’re out here on behalf of my soul, so they say, but I’m not sure what they think’s going to happen to it. All any of them know about this movie is what somebody else has told them, and who knows if those people know what they’re talking about.”

And if they all saw it and still decided it was a menace? Would he listen to them then?

“Not likely,” Joey snorts. “Why should I think they really care about my soul when none of them seems to mind it’s been dying of boredom for years already?”

Today being a notable exception, perhaps?

Joey glances back at his friends before answering. Even on the wrong side of Ardmore there are images to uphold. No, he’s bored today too, he claims, it’s just that today there’s something to do. His grin is as cheerful as ever.

Then his expression turns serious, curious. As though he hopes that someone not from around here may be able to level with him in a way that his neighbors can’t.

“Is it true what some people are saying about this movie?” he asks. As though the mere possibility could be liberating. “That it wasn’t just inspired by Hell…that that’s actually where it comes from?”

*

*** WARNING! SPOILER ALERT! ***

For the millions denouncing the film, the problem with The Passion of the Beast can’t be that the devil plays a prominent role. He popped up several times in the Gibson film, after all. And it can’t be because this particular devil has a strong point of view. So did Mel’s. Hell, any devil without a point of view isn’t much of an adversary.

This one is. In the most archaic, Hebraic sense of the word.

For perhaps the first time in cinematic history, we get a Satan that conforms to his assigned role from the earliest texts of the Old Testament. This isn’t Ernest Borgnine’s cheesy goat-man from The Devil’s Rain, or the malevolently hunky Viggo Mortensen, pre-Aragorn, gobbling Christopher Walken’s renegade angel-heart in The Prophecy. Nor is this the androgynous, shaven-headed monk from The Passion of the Christ, whose robe hem spills occasional creepy-crawlies.

Instead we have here one devil of a paradox: a Satan with a firm scriptural basis, yet who is all but unknown, or otherwise denied, by most of the well-intentioned Christian soldiers marching as to war. Before “Satan” evolved into a name, the word was, in the ancient Jewish texts, more of a title: “the Adversary,” or “the Accuser,” a being interpreted by many scholars to be not an enemy seeking the destruction or enslavement of all creation, but rather a pesky celestial attorney charged with the task of prosecuting the case that not all of God’s ideas are necessarily good ones. While the other angels are yes-men, Satan steadfastly plays the thankless role of the ultimate Captain Bringdown for a God from whom everything emanates; the

God who, in the book of Isaiah, says, “Who fashions light and creates darkness, who makes peace and creates evil? I am HaShem who does all this.”

So yes, this is still a Satan who tries his damnedest to prevent the crucifixion. But he appears to do so out of love, showing a benevolent uncle’s affection for Jesus, as well as logic, his central argument being that martyrdom can only distort the prophet’s message. It’s an argument that gets several increasingly passionate airings—constantly refined with an alacrity that would do any contemporary lawyer proud—as during the countdown to the crucifixion Satan gains an audience with various Jewish and Roman officials who presumably have no idea who or what he is.

Nor do they seem to care what he has to say. Like most politicians, their vision is hopelessly limited to immediate concerns. Satan, taking the long view—which is recognizable only to our luxury of hindsight—appears to be fixated on pogroms and crusades that lie far in the future.

In the end, then, this is a Satan condemned to ineffectuality, seeing his best efforts rebuffed and thus forced to bear witness to an inexorable progression toward the savage execution of a prisoner who clearly wants to go through with it. And does. Step by gruesome step.

That Mel Gibson’s influence is all over this movie, however unintentionally, should be obvious to even the most casual observer. As with his version, the subtitled dialogue is in Latin and Aramaic (with a little Greek thrown in for…what, originality?). At times it could be a shot-for-shot remake. At other times it deviates wildly in style as well as substance. Gone are the self-conscious flourishes that tell viewers when they’ve come to a point of Great Importance—no slow motion to underscore the obvious, no evil children hounding Judas to his death, no orchestral and choral soundtrack pounding as hard as the hammers atop Golgotha.

Controversial subject aside, the choice of a title almost identical to that of the Gibson film is clearly, perhaps even cynically, calculated to inflame. It certainly isn’t satirical, although it is perhaps ironic: This is not the Beast of Revelation.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

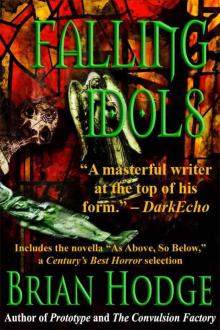

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols