- Home

- Brian Hodge

Worlds of Hurt Page 6

Worlds of Hurt Read online

Page 6

I remembered the way my mother reacted when I told her what the blood-kissing angel had said on that day of the bomb. This is the kind of work you can expect from people who have God on their side. I’d not made it up, only repeated it, but my mother hadn’t wanted to hear another word. Hadn’t wanted to know any more about that woman who’d comforted me as my friends lay dead. It hurt me now much more than it had then. How rigid our fears can make us; how tightly they can close our minds. I wondered aloud why the uncomplicated faith that ran like a virus through the generations of our family hadn’t been enough for Brendan and me.

“Wondered that myself, I have,” he admitted. “Who knows? But I like to think it might be our Celtic blood. That it’s purer in us, somehow, than it is in the rest of the family…and the blood remembers. Greatest mystics that ever were, the Celts. So you and I…could be we’re like those stones they left behind.”

“How’s that? The standing stones?”

“Aye, the very ones,” Brendan said, and I thought of them settled into green meadows like giant gray eggs, inscribed with the primitive ogham alphabet. “Already been around for centuries, they had, by the time the bloody Christians overrun the island and go carving their crosses into the stones to convert them…like they’re trying to suck all the power out of the stones and turn them into something they were never intended to be. But the stones remember, still, and so do we, I think, you and I. Because our blood remembers too.”

The blood remembers. I liked the sound of that.

And if blood could only talk, what stories might it tell?

* * *

The stigmata still came, the flow of blood awe-inspiring to me, still, but there was something shameful about it now, as if leaving the Franciscans had made me unworthy. Worse, it terrified me now more than ever, for I exhibited the wounds of a Christ who had denied himself. They came like violent summons from something beyond me, indifferent to what I did or didn’t believe in.

They knew no propriety, no decorum. One night, soon after I’d confessed to my uncle that I’d never been with a woman, he paid for me to enjoy the company of one who certainly didn’t live in the area, and then stepped discreetly from the house to share a drink with a neighbor. They’d scarcely tipped their glasses before she ran from the house and demanded he take her back to Limerick. Brendan first came in to see what had upset her so, and found me sitting on the bed with my wounds freshly opened.

“Oh suffering Christ,” he said, weary and beaten. “Ordinarily it’s the girl who bleeds the first time.”

For days I felt stung by the humiliation, and the loneliness of what I was, and tried to pull the world as tight around me as it had been at the friary. Once a cloister, now a boat. I’d leave the docks early in the morning, rowing out onto Lough Derg until I could see nothing of what I’d left behind, and there I’d drift for hours. Chilled by misty rains or cold Atlantic winds, I didn’t care how cruelly the elements conspired against my comfort. The dark, peaty waters lapped inches away like a liquid grave.

I often dwelt upon Saint Francis, whose life I’d once vowed to emulate. He too had suffered stigmata, had beheld visions of Jesus. Francesco, repair my falling house, his Jesus had commanded him, or so he’d believed, and so he’d stolen many of his father’s belongings to sell for the money it would take to get him started. Repair my falling house. Whose Jesus was more true? Mine appeared to want from me nothing less than that I tear it down.

But always, my reflections would turn to that which to me was most real: she who had come on the day of the bomb. Who smiled reassuringly at me with my blood on her lips, then never saw fit to visit again. A poor guardian she’d made, abandoning me. Since I’d been a child kneeling beside my bed at night, I had prayed to every evolving concept of God I’d held. I’d prayed to Savior and Virgin and more saints than I could recall, and now, adrift on the dark rippling lake, I added her to those canonical ranks, praying that she come to my aid once more, to show me what was wanted of me.

“You loved me once,” I called to her, into the wind. “Did I lose that too, along with all the blood?”

But the wind said nothing, nor the waters, nor the hills, nor the skies whence I imagined that she’d come. They were as silent as dead gods who’d never risen again.

In the nights that followed these restless days, I learned to drink at the elbow of a master. No more shandies for me—the foamy black stout now became the water of life. Women, too, began to lose their mystery, thanks to a couple of encounters, the greater part of which I managed to remember.

And when I couldn’t stand it any longer, I broke down and told my uncle the secrets that had been eating away at me—the one for only a few weeks, the other since I was seven. It surprised me to see it was the latter that seemed to affect him most. Brendan grew deathly quiet as he listened to the story of that day, his fleshy, ruddy cheeks going pale. He was very keen on my recounting exactly how she’d looked—black hair shimmering nearly to her waist, her skin a translucent brown, not like that of any native I’d ever seen, not even those called the Black Irish.

“It’s true, they really do exist,” Brendan murmured after I’d finished, then turned away, face strained between envy and dread, with no clear victor. “Goddamn you, boy,” he finally said. “You’ve no idea what’s been dogging your life, have you?”

Apparently I did not.

He sought out the clock, then in sullen silence appeared to think things over for a while. When at last he moved again, it was to snatch up his automobile keys and nod toward the door. Of the envy and dread upon his face, the latter had clearly won out.

IV. De contemptu mundi

“Somebody once said—I’ve forgot who—said you can take away a man’s gods, but only to give him others in return.”

He told me this on our late-night drive, southwest through the countryside, past hedgerows and farms, along desolate lanes that may well have been better traveled after midnight. A corner rounded by day could have put us square in the middle of a flock of sheep nagged along by nipping dogs.

Or maybe we traveled by the meager luster of a slivered moon because, of those things that Uncle Brendan wished to tell me, he didn’t wish to do so by the light of day, or bulb, or fire.

“Wasn’t until after I’d left seminary that I understood what that really meant. You don’t walk away from a thing you’d thought you believed your whole life through without the loss of it leaving a hole in you, hungering to be filled. You’ve still a need to believe in something. It’s just a question of what.”

Sometimes he talked, sometimes he fell silent, collecting his remembrances of days long gone.

“I tried some things, Patrick. Things I’d rather not discuss in detail. Tried some things, and saw others…heard still other things beyond those. You can’t always trust your own senses, much less the things that get whispered about by people you can’t be sure haven’t themselves gone daft before you’ve ever met them. But some things…

“That woman you saw? One of three, she is, if she’s who I think she was. There’s some say they’ve always been here, long as there’s been an Ireland, and long before that. All the legends that got born on this island, they’re not all about little people. There’s some say that from the earliest times, the Celts knew of them, and worshipped them because the Celts knew that the most powerful goddesses were three-in-one.”

We’d driven as far down as the Dingle Peninsula, one of the desolate and beautiful spits of coastal land that reached out like fingers to test the cold Atlantic waters. The land rolled with low peaks, and waves pounded sea cliffs to churn up mists that trapped the dawn’s light in spectral iridescence, and the countryside was littered with ancient rock: standing stones and the beehive-shaped huts that had housed early Christian monks. Here hermits found the desolation they’d craved, thinking they’d come to know God better.

“There’s some say,” Uncle Brendan went on, “they were still around after Saint Patrick came. That sometimes, in

the night, when the winds were blowing and the waves were wearing down the cliffs, a pious hermit might hear them outside his hut. Come to tempt him, they had. Calling in to him. All night, it might go on, and that horny bugger inside, all alone in the world, sunk to his knees in prayer, trying not to imagine how they’d look, how they’d feel. No reason they couldn’t’ve come on in as they pleased. It was just their sport to break him down.”

“Why?” I asked. “To prove they were, what, more powerful than his god was?”

“Aye, now that could be. More powerful…or at least there. Then again, some say that, by the time the Sisters of the Trinity finally got to their business on those who gave in, all the hours of fear…it flavored the monks better.”

“Flavored? Their blood, you mean?”

“All of them. It’s said each consumes a different part of a man. One, the blood. One, the flesh. And one, the seed. It’s said that when they’ve not fed for a good long time? There’s nothing of a man left but his bones, cracked open and sucked dry.”

I couldn’t reconcile such savagery with the tenderness I’d been shown—the sweetness of her face, the gentle sadness in her eyes as she looked upon us, two dead boys and the other changed for life. Only when she’d tasted my blood had anything like terrible wisdom surfaced in her eyes.

The sun had breached the horizon behind us when Uncle Brendan stopped the car. There was nothing human or animal to be seen in any direction, and we ourselves were insignificant in this rugged and lovely desolation. We crossed meadows on foot, until the road was lost to sight. Ahead, in the distance, a solitary standing stone listed at a slight tilt; it drew my uncle on with quickened steps. When we reached it, he touched it with a reverence I’d never thought resided in him, for anything, fingers skimming the shallow cuts of the ogham writing that rimmed it, arch-like.

“It’s theirs. The Sisters’. Engraved to honor them.” Then he grinned. “See anything missing?”

I looked for chunks eroded or hammered away, but the stone appeared complete. I shook my head, mystified.

“No crosses cut in later by the Christians. It wouldn’t take the chisel. Tried to smash the rock, they did, but it wore down their sledges instead. Tried to drag it to the sea, and the ropes snapped. So the legend goes, anyway. Like trying to pull God’s own tooth. Or the devil’s. If there’s a difference.” He shut his eyes, and the wind from the west swirled his graying hair. When he spoke again, his voice was shaking. “Killed a boy here once. When I was young. Trying to call them up. I’d heard sometimes they’d answer the call of blood. Maybe I should’ve used my own instead. Maybe they’d’ve paid some mind to that.”

On the wind I could hear the pounding of the ocean, and as I tried to imagine my generous and profane uncle a murderer, it felt as if those distant waves had all along been eroding everything I thought I knew. I asked Brendan what he’d wanted with the Sisters.

“They didn’t take the name of the Trinity just because there happens to be three of them. Couldn’t tell you what it is, but it’s said there’s some tie to that other trinity you and I thought we were born to serve. Patrick, I…I wanted to know what they know. And there’s some say when they put their teeth to a man, the pleasure’s worth it. So what’s a few years sacrificed, to learning what’s been covered up by centuries of lies?”

“But what if,” I asked, “all they’d have to tell you is just another set of lies?”

“Then might be the pleasure makes up for that, too.” He took a step toward me and I flinched, as if he had a knife or garrote as he would’ve had for that boy whose blood hadn’t been enough. Brendan raised his empty hands, then looked at mine.

At my wrists.

“Maybe you’ve the chance I never had. Maybe they’ve a use for you they never had for me.”

And in the new morning, he left me there alone. I sat against the old pagan stone after I heard the faraway sound of his car.

The blood remembers, he’d once told me, and so do we.

Demon est Deus inversus, I’d been told by another. Save me from that impotent, slaughtered lamb they have made of me.

On this rock will I build my church, some scribe had written, putting words in the latter’s mouth.

The blood remembers.

Three days later my flesh remembered how to bleed.

And the stone how to drink.

* * *

Regardless of their orbits, planets are born, then mature and die, upon a single axis, and so the stone and those it honored had always been to me, even before I knew it. Now that I was here, I circled the stone but wouldn’t leave it, couldn’t, because, as in space, there was nothing beyond but cold, dark emptiness.

They came while I slept—the fourth morning, maybe the fifth. They were there with the dawn, and who knows how many hours before that, slender and solid against the morning mists, watching as I rolled upright in my dew-soaked blanket. When I rubbed my eyes and blinked, they didn’t vanish. Part of me feared they would. Part of me feared they wouldn’t. As I leaned back against the stone, she came forward and went to her knees beside me, looking not a day older than she had more than twenty years before. Her light brown skin was still smoothly translucent. Her gaze was tender at first, and though it didn’t change of itself, it grew more unnerving when she did not blink—like being regarded by the consummate patience of a serpent.

She leaned in, the tip of her nose cool at my throat as she sniffed deeply. Her lips were warm against mine; their soft press set mine to trembling. Her breath was sweet, and the edge of one sharp tooth bit down to open a tiny cut on my lip. She sucked at it as if it were a split berry, and I thought without fear that next I would die. But she only raised my hands to nuzzle the pale inner wrists, their blue tracery of veins, then pushed them gently back to my lap, and I understood that she must’ve known all along what I was, what I was to become.

“It’s nice to look into your eyes again,” she said, as if but a week had passed since she’d done so, “and not closed in sleep.”

Since coming to the stone I’d imagined and rehearsed this moment countless times, and she’d never said this. She was never dressed in black and grays, pants and a thick sweater, clothes I might’ve seen on any city street and not thought twice about. She’d never glanced back at the other two, who eyed each other with impatience while the taller of them idly scraped something from the bottom of her shoe. She’d never simply stood up and taken me by the hand, pulled me to my feet, to leave me surprised at how much smaller she looked now that I’d grown to adulthood.

“He stinks,” said the taller Sister. From the feral arrogance in her face, I took her to be the flesh-eater. “I can smell him from here.”

“You’ve smelt worse,” said the third. “Eaten it, too.”

As I’d rehearsed this they’d never bickered, and my erstwhile angel—Maia, the others called her—had never led me away from the stone like a bewildered child.

“Where are we going?” I asked.

“Back down to the road. Then back home to Dublin,” Maia said.

“You drove?”

The flesh-eater, her leather jacket disconcertingly modern, burst into mocking laughter. “Oh Jesus, another goddess hunter,” she sighed. “What was he expecting? We’d take him by the hand and fly into the woods?”

The third one, the sperm-eater by default, slid closer to me in a colorful gypsy swirl of skirts. “Try not to be so baroque,” she said. “It really sets Lilah off, anymore.”

V. Sanguis sanctus

They were not goddesses, but if they’d been around as long as they were supposed to have been, inspiring legends that had driven men like my uncle to murder, then as goddesses they at least must’ve posed. They were beautiful and they were three, and undoubtedly could be both generous and terrible. They could’ve been anything to anyone—goddesses, succubi, temptresses, avengers—and at one time or another probably had been. They might’ve gone through lands and ages, exploiting extant myths of triune women, leaving o

thers in their wake: Egyptian Hathors, Greek Gorgons, Roman Fates, Norse Norns.

And now they lived in Dublin in a gabled stone house that had been standing for centuries, secluded today behind security fences and a vast lawn patrolled by mastiffs—not what I’d expected. But I accepted the fact of them the same way I accepted visions of a blaspheming Christ, and ancient stones that drank stigmatic blood, then sang a summons that only immortal women could hear. All these I accepted as proof that Shakespeare had been right: there were more things in Heaven and Earth than I’d ever dreamt of. What I found hardest to believe was that I could have any part to play in it.

They took me in without explaining themselves. I was fed and allowed to bathe, given fresh clothes. Otherwise, the Sisters of the Trinity lived as privileged aristocrats, doing whatever they pleased, whenever it pleased them.

Lilah, the flesh-eater, aloof and most often found in dark leathers, had the least to do with me, and seemed to tolerate me as she might a stray dog taken in that she didn’t care to pet.

The sperm-eater was Salíce, and while she was much less apt to pretend I didn’t exist, most of her attentions took the form of taunts, teasing me with innuendo and glimpses of her body, as if it were something I might see but never experience. After I’d been there a few days, though, she thrust a crystal goblet in my hand. “Fill it,” she demanded, then pursed her lips as my eyes widened. “Well. Do what you can.”

I managed in private, to fantasies of Maia.

I’d loved her all my life, I realized—a love for every age and need. I’d first loved her with childish adoration, and then for her divine wisdom. I later loved her extraordinary beauty as I matured into its spell. Loved her as an ideal that no mortal woman could live up to. I’d begun loving her as proof that the merciful God I’d been raised to worship existed, and now, finally, as further evidence that he didn’t.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

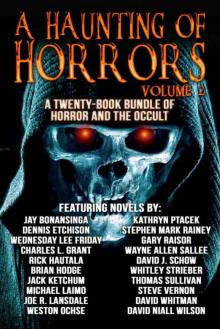

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols