- Home

- Brian Hodge

Prototype Page 7

Prototype Read online

Page 7

Adrienne smiled, a thin, shrewd, dealmaker's smile that just managed to conceal her irritation that he did not wholly trust her word.

"Thank you, Ferris," she said, and knew just when to leave.

*

The psycho ward didn’t allow televisions in the rooms — this was a surprise? On or off, TVs were notorious for implanting thoughts into heads. Clay had conversed with few of his ward mates, but enough to conclude that as far as most were concerned, denying them unlimited video access was wise. There was a large set in the dayroom, but it usually remained under the control of the staff, and whoever feared its influence — the home of the cathode-ray gods, perhaps — did not have to come near it.

Clay, however, soaked it up whenever he was able.

A tie to home; whenever he was home the TV was always on, although he didn't know why. It commanded attention, if not respect. He viewed it not as entertainment, but as a conduit of information. He could wire in with optic and auditory nerves; pipe in news and documentaries, commentary both rational and apocalyptic. He could define the state of the world in any given half hour, and it was always maddened.

Fringe shows on syndication and cable access were best, the gleam on the cutting edge of media psychosis.

It took him a week of attempts, whenever TV security was lax, to locate The Eye of Vigilance, coming out of a Phoenix station. It had a late-night time slot in Denver, but early-evening here. Curious. Perhaps in Arizona it met with a wider receptive audience.

Clay's rational side found that mildly scary, while the deconstructionist rejoiced — one more sign of Armageddon.

The Eye of Vigilance was the half-hour province of one Milton Wheeler, who lorded over his airwaves from behind a polished oak desk, and whose introductory fanfare announced to sycophants and heretics that he was "appointed by God as the conscience of the nation." No one knew if he really believed this or not, but it never hurts to call in the big guns.

There was much that made him rabid, and this stocky fellow with wagging jowls and manicured hands and his glasses slightly askew railed against it all with varying degrees of eloquence, sometimes with guests at his side, sometimes taking phone calls, and he was absolutely full of shit. This was, for Clay, the main attraction. Milton Wheeler was an idol in the making and could not lose. If he lived, the far right would eventually canonize him. If he were killed, then he would be its martyr.

Though for all Wheeler's propagandizing, Clay found that every now and again he did make an eerie kind of sense.

Monday evening, mid-October, an epiphany:

"A stranger is just an enemy you haven't assessed yet," he said, and the studio audience murmured its agreement.

"Did you hear that?" It was the patient in the chair beside Clay, forty years of twitches mellowing under medication. She always held two fingers as if they clamped a cigarette.

"Yeah," said Clay.

"Do you believe that?"

"I think so. Don't you?"

She pointed at the TV with her two fingers that never did anything alone. "That fat little man wants to be Jesus. Only he's too heavy, he'd tear loose and fall off the cross. That's why he's so pissed off all the time."

Clay cocked his head, staring at the screen, considering this. He half-shrugged, half-nodded. It was as good an explanation as any for what motivated the man. "But they make better nails now."

"Well, somebody needs to go tell him, then." She brought her fingers to her lips and, with no cigarette to puff, scratched her chin. "Are you busy now?"

"I'm waiting," he told her, inspired by the unlikely wisdom of Milton Wheeler and this woman's messianic imagery, "for a table to be prepared for me in the presence of my enemies."

"Oh," she said. "Okay."

Clay watched until a nurse came along and noticed what was playing and switched to something less volatile, so he returned to his room and endured sundown — hated cusp of transition and advent of shadowed menace. The world stopped at the window, but the barrier was only glass and metal. Everything had a melting point.

A stranger is just an enemy you haven't assessed yet.

He had learned this lesson early in life, had merely failed to qualify it so succinctly. And fathers and mothers are never so honest as to prepare their malignant offspring for the social abortion the world is sure to perform on them.

But, inquisitive Adrienne, doesn't everybody wake up one day to realize his childhood was never the norm? Statistically speaking, neither mean, median, nor mode.

Doesn't everybody blame himself for failure to fit in, by deed if not conscious admission, and self-inflict the punishment due? A razor blade makes fine slices on arms and legs and torso, but a penknife is even better, thicker of blade and duller by increments; the skin resists its pressure before giving way, and the sensation is so much more real. And blood makes splendid ink with which to write indictments against oneself.

Doesn't everybody get together to compare scars for severity, frequency, aesthetics?

Doesn't everybody?

Of course not. Only the survivors.

He learned early in adolescence that life was nothing if not full of dichotomies. High school stank of contradictions, and what is high school but a model of the greater world? Even in rebellion there is conformity, while even among outcasts one can find refuge.

He and his friends of that era banded together mostly by default. The despised and the rejected, the hated and the brutalized, they auditioned one another with bravado or indifference or threats, almost by instinct, and found kindred souls in their solitude. Athletes and scholars, socialites and thespians … they were none of these, looking upon those who were with scorn. In time Clay realized they did so mainly because, as deviants who felt too much or too little or looked wrong, they had no choice. They resented what they could never be, what they would never be allowed to be. I rejected you first, they seemed to scream inside, and most fooled themselves into believing it was true.

Clay learned to appreciate the irony: Even among their small, pitiful ranks he did not wholly belong.

For he alone recognized the fundamental truth that people seem to function best when they have someone to hate. Nothing else stirs blood so energetically, or heats such emotion. Nothing else motivates with such ferocity. Nothing else flickers so brightly in dying eyes.

Crusades had been launched and wars declared, lands besieged and races exterminated, because someone had refined their hatred of the different, of the other, into something they could wield as effectively as a weapon. It was progress.

And there were times when Clay wondered, if there really was a God, if He hadn't created the world because He’d already known He would hate it.

These things the teenage Clay understood, day by day, year by year. Every fresh scar carved upon his body, and drop of blood spilled, and each tear that squeezed free of his eye, just seemed to confirm it.

Tears…? Even these. A world ignored may react with indifference, but a world hated seeks its own revenge.

A stranger is just an enemy you haven't assessed yet.

With the sun fallen beyond window and horizon, Clay moved across the room to stare out into the night. The ceiling light still burned, and the glass just beyond the chain mesh became a ghostly mirror that floated against the black. There hung his face and shoulders, little more than outlines; a faint glimmer of each eye, the suggestion of his mouth, his nose; the rest obscured.

There, against the night: a stranger to himself, a living portrait of the enemy within.

Seven

Adrienne proved to Mendenhall's satisfaction that a simple genetic karyotype would break no hospital bank account, even if insurance balked, and she was given clearance to have it run.

That Wednesday afternoon she came in early, escorted Clay down to the lab where a tech sampled his essences: a few hairs plucked from his scalp, and, to be thorough, a bit of blood drawn from his arm. Quiet and still, she gazed down as he submitted to the needle, watched it pierce skin,

watched the vial fill with ruby brilliance. On his bared arm were the ghosts of old scars, five or six, white, emphatic like accent marks in a private language.

"Today's the thirteenth," he said, "isn't it?"

"Right." She found it fairly remarkable the way he kept track without a calendar.

"Maybe that's a bad omen." Clay frowned as the lab tech pressed a cotton ball over the violated vein.

"You never seemed superstitious before."

He raised his arm for a minute, as instructed by the tech. "And maybe I'm not serious."

Sometimes, she had to admit, it was not easy to tell.

The samples were packaged and sent across town by courier, to Arizona Associated Laboratories' bio-med division, on University. It was out of her league, but a fascinating procedure nonetheless. As she understood, it involved taking a cellular sample — a hair follicle, say, or plasma — and chemically treating it to suspend the movement of the chromosomes in cells undergoing division at that moment. The cells were then squashed and smeared across a glass microscope slide and stained to improve visibility. The inventory of chromosomes in a single cell's nucleus was then photographed through the microscope, after which each chromosomal image was cut from the print, sorted according to size and structure, matched into corresponding pairs, then pasted into a composite photo.

Any gross abnormality such as an extra Y sex-chromosome could not escape detection. The karyotype was a living diagram.

They would wait, they would see, and she would prove his fears groundless.

Later that afternoon, his session, on schedule: October sun slanting through the window, and the insistent whisper of the tape recorder, tiny cassette reels spinning to immortalize Clay's silence from the couch.

Eventually: "You were looking at the scars, weren't you?" He wore the long engulfing sleeves of a robe but proffered both arms anyway. "I noticed that."

"Yes. They caught my eye."

"What did you think of them?"

"I don't know as I thought anything about them, per se." Which was a lie, a little professional white lie; allowable, even expected. She had continued to see those pale, thin remnants of past slashes long after his sleeve had gone back down, wondering how they would feel beneath her fingers. There was nothing sexual about it; just the imagined tactility of hardened ridges. If there were enough of them, intersecting, they might feel like a chaotic web in which he chose to protect himself.

"Scars are benign, of themselves," she went on. "Where you're concerned, what interests me is the story behind them. The events and emotions that put them there."

"We've been over that before."

Nodding toward him, very slightly, with upraised eyebrows. Body language, when the words themselves might have been too harsh: You brought it up. He appeared almost sheepish.

"Twinkle, twinkle, little scar," Clay said. "You hadn't seen any of them before. I just wondered." Biting his lip then. While he usually seemed to resent it when she left him to stew in his own silence, he was handling it better with every session. "It was sport, I told you that, I think. Didn't I? Sometimes it was just endurance. Sometimes it was a rehearsal for something worse that I never ended up doing to myself."

"Suicide, you mean."

"I thought about it a lot."

"But not anymore."

He sat back against the couch. "It's been a few years." Contemplation, like shuffling through a photo album with nothing but grim black-and-whites: crime scenes and accident victims; his young life. "Maybe it just didn't seem romantic anymore. You can get jaded about anything." This struck him as amusing. "Self-destruction can get kind of old and pretentious if you keep after it long enough. If you don't eventually off yourself, you're just a poseur."

Adrienne found herself tracking down an intriguing line of thought that Clay would, naturally, be too blind to see about himself. "So you put down the knife one day and decided, No more."

"More or less."

"Yet you've received several scars since then."

Clay raised his head fractionally, wary — somewhat amused but tempered with something grimmer, as well, some spiny little paranoia. "So?"

Tightroping over the session once again, hoping instinct still served her well — that he was ready to be confronted with the obvious and could deal with it.

"So is it possible that you put away your knife, but turned the same task over to others … one of whom might be willing to do a more thorough job?"

Sun at her back and the soft, soft sound of the cassette. She was never more aware of it than at moments such as this, when words and eye contact and even the air in the room congealed.

"Death wish, huh?" Clay's grin was shy and menacing by turns, depending on the tilt of his exquisitely contoured head. Biting his lip as he watched her with narrowed eyes, as if one moment hating her for finding him out, congratulating her for it the next. "Did it ever occur to you that maybe I decided I liked feeling other people's skin give way under my hands instead of my own?"

A lie. No, not exactly, more a rationalization. A defensive barrier thrown up hurriedly, enough to block her but not sturdy enough to fool her. Clay would know that, wouldn't he?

"That sounds like something that would come from a predatory outlook. From what I've seen about you, what I know about you, and the incidents that have gotten you into trouble, you don't fit the predator mold."

He stared down toward his casts. After three weeks they had gotten dingy, the pristine white given way to a more lived-in look. "I guess," he said, and looked at her in surrender, even embarrassment, "I just overreact."

Gently, Adrienne nodded. She had been sitting with one knee draped over the other, leaning back, relaxed or trying to at least give that impression, but now she dropped both feet to the floor and slid forward, edge of the seat.

Oh, what she could learn from him, given the time and the freedom.

"Whether they realize it or not, people usually overreact because they're feeling threatened. And not always by anything so obvious as three gang-bangers trying to relieve them of the last of their cash."

While she left this with him, Adrienne combed mental files. Trying to call up those incidents in which Clay's impulses got the worst of him. The destruction — merely mindless, or cannily directed? — he could leave in his wake. Shattered glass doors in convenience store coolers; BMW pounded halfway to the scrapyard with a lead pipe; parking lot rammings of the cars of cocky drivers with more insurance than sense. Yes, there had been fights too, but were his incidents of vandalism sudden ventings of rage to keep him from harming others? Or unconsciously chosen symbols of a world he despised?

Clay shifted back and forth on the couch — all at once he just couldn't get comfortable there. So he left it, wandered across the room until he could sag against the windowsill and stare out at a world he'd not been part of for nearly three weeks.

"I thought about trying to become a Buddhist once," he said to the glass, to a world that would never hear him, "because they always seem so peaceful. That was very appealing, I thought it might help." He had begun to rhythmically strike his casts together, clunk clunk clunk, hammer and anvil, harder, louder — how must that feel vibrating through his knitting bones? Then he stopped. "But it's so passive, I just … I couldn't.

"But I did read this story that made so much sense. A story about Buddha. Someone came up to him, trying to figure out what it was about him that made him so wise, so in tune. They asked him, 'Are you a god?' He said, 'No.' Then they tried again, 'How about a saint, are you a saint?' Same thing, 'No.' Finally had to ask, 'Well, what are you, then?' And Buddha said, 'I am awake.'"

Adrienne smiled. It was a beautiful little fable and for a moment she thought how much Sarah would love it, its profound simplicity. But Clay had not shared it in delight, and she watched as he knocked his head against the window, eyes shut, breath fogging the glass.

"You related to something in that story," she said.

"I woke up one day, or month,

or year — who knows how long it took, these things never just come over you full-blown, it takes time. I mean, I know there's something seriously screwed up about me, too, but … I started seeing everything around me for what it was. And I realized it was all I could do to stand it, living in a world where everybody seems satisfied with so little. I'm not talking about material things, I mean their lives. Give them their little ruts and they're happy. Or maybe not, but they settle for it, because they don't know any other way out. And nobody encourages them to find it."

Adrienne dared not interrupt his flow, watching as he drew himself together, stood taller, squarer at the window.

"It's all just part of the grand mediocracy," he said.

"Mediocrity, you mean?"

Clay shook his head. "Mediocrity is a quality. Mediocracy is the process that perpetuates it." He must have noticed her vague uncertainty. "The word, I mean, I made it up."

She nodded, and liked the word a great deal.

He explained: "In a democracy, the people are in charge. Theoretically. In an autocracy, it's a despot. In a theocracy, the church rules. So, in a mediocracy…" He left it open, passing it to her.

"Society is ruled by that which is mediocre," she finished, feeling a click within, a reversal of roles. He had become the lecturer and she the pupil.

She had wanted to learn from him? Of course. She had just thought she would remain in charge the whole time, and in a small way hated to lose the moment when she saw him turn again, back to the window, to stare. Hated world, intolerable world, world that rejects and is rejected.

"I'm awake," he whispered, "but all it does is hurt."

*

She thought of ruts over the next couple of days. How easy to fall into them, how difficult to recognize them from inside. Was she living in one as of late?

She worked, she treated patients. She came home, she slept. Books, always there to be read, nonfiction mostly, biographies and psychology texts, the occasional mystery. Her parents had retired two years ago to Prince Edward Island and she faithfully wrote them every other week. Now and again, a drive into the desert to watch the dawn, and feel the warming embrace as the newborn sun scorched the purity of land, to remember why she had come down here. Anything else? No, not much of note.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

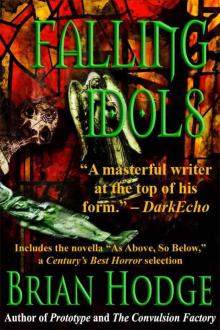

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols