- Home

- Brian Hodge

Deathgrip Page 8

Deathgrip Read online

Page 8

Lorraine gathered her clothes from the living room floor, carried them to his bedroom doorway. Could she borrow his shower, and he gave her his blessing, even proved it by fetching a fresh washcloth and towels from the narrow linen closet.

The water surged on, causing a brief shuddering of pipes and walls — bathquake. When he heard the metallic clitter of the shower curtain circling the rod, he wandered to his kitchen wall phone and dialed KGRM’s request line. Talking to Peter, please please take my airshift too, I can’t handle things today, and maybe you could make up some bullshit excuse for Popeye while you’re at it. Pete, who wasn’t so wicked after all. Remembering who had been the final two left last night, he quickly fit the puzzle together. No problem, he said.

They signed off, and Paul stepped into a pair of gym shorts doing double duty as an oven mitt these days. A few minutes later, Lorraine poked her head from the bathroom, wisps of humid steam accompanying her in ephemeral wreaths.

“Do you have any deodorant I can borrow?”

Paul retrieved it from his bedroom dresser, handed it over as she half-hid herself in the doorway, towel knotted between her breasts. Not so uninhibited today, are we, and he caught himself. No spite, not toward her.

“Thanks.” She inspected the label, her hair a wet blond curtain. “Old Spice. Great. I’ll smell like a sailor all day.”

“Probably get the urge to pee standing up, too.”

It was like that for the duration, trading quips with an almost desperate need to do so. As if it would shield them from dwelling on the previous night and its implications. Keep a nice safe lid on the longings and the regrets and the suppressed urge to grab each other and reprise last night’s magic and this time try for bona fide wizardry. It was either that, or make each other laugh. Emotional Tupperware; seals the humor in, keeps the passion out.

At last came the dreaded moment after which nothing would truly be the same, and life would have to go on as before, if only in appearance. She had to leave, and he did not argue. Arguments led to irretrievable remarks and loss of dignity. No thanks. They faced each other at the door, stricken with a sudden loss for words. Having to suffice with a stiff, awkward hug during which he could smell his shampoo in her hair, and a mumbled, See you later, okay? Okay.

The door latched after her with the final slam of a bank vault whose riches would remain forever locked within, eternally in the dark, to collect only rust. He listened to her fading footsteps until he couldn’t.

Now, at last, honesty with self. No more fronts to put on, nor stiff upper lips to exhibit. Slowly backing from the threshold. There came no moment of fist-through-wall fury, no cyclone of destructive energy. Only the sad regret, glacial in its chill, if only, if only, the Ice Age of the heart.

He retreated to the sofa in miserable defeat, with KGRM on low for company, a much-needed friend. He drew knees to chest while turning his back on the room, the world, sinking into a profound quagmire of pain. Self-pity was allowed within your own four walls, here comes the bitter flood. He wept. He wept.

But along about three o’clock, he knew that perhaps he could survive after all. While dashed hopes may have run deep, they had been short-lived, less than twenty-four hours old. Their roots could have gone far deeper. Perhaps he might get over things one step at a time, so long as he could still stand.

After all, Lorraine was managing.

“I want to get serious here, before going any further,” she said over the air, to an entire city and beyond. “You’ve heard it before, I know, from everybody who’s been on the air since yesterday afternoon. We’re all shocked and saddened by what happened at The House of Wax. There’s no way we can expect to understand why something like that happens, but it touches us all, one way or another.

“So let’s all lean on one another a little harder, okay? Try to be patient with each other, and remember what’s important in life. And if we screw up now and then, and if we say or do the wrong thing at the wrong time, let’s not forget to say we’re sorry for whatever pain we might have caused. We owe each other that much, at the very least. Don’t we?”

Paul turned over to face his apartment, his world, for the first time in hours, and she played her first song of the day:

Vintage Fleetwood Mac, “You Make Loving Fun.”

He needed a walk. In the worst way. Lorraine’s opening remarks — that first crusted scab of healing — were but an hour old, and he needed a walk. One more minute of staring at these walls would render him in need of a straitjacket.

He slipped into some exquisitely faded and comfortable Levi jeans and one of those white muscle shirts emblazoned with red and black Japanese emblems. He took his car southeast a couple miles, into Forest Park. He abandoned the car on one of the winding drives near the zoo, then took off on foot, following a meandering eastern path.

He kicked around shaded bowers, watched people of infinite variety, all ages. Walking dogs, or jogging, or hurling Frisbees back and forth. Living their own private lives, so separate from his own, and he wished them well. He bought a chili Polish and a liter of Pepsi, breakfast of chumps, and strolled along.

At the eastern border of the park, Kingshighway was nearly jammed to capacity with rush hour traffic. He stared across it, beyond, at the huge health complex. At, in particular, Barnes Hospital. Long catatonic moments in contemplation, eyes never leaving its walls and windows, acknowledging the subconscious drive that had no doubt led him here. He felt summer sun, summer wind, but experienced them secondhand. He was that far inside himself.

He had already checked: He knew who was here. Knew why he was here. Deep down, he knew.

What I did the other day with Peter, and he felt a little silly even voicing this to himself, could that have been real?

It had nagged and nibbled at him ever since last week. Time now to put it to the test. He took life in hands and found a spot to cross Kingshighway and headed on into Barnes. A whim. On a dare with self. Obligation.

Inside was a labyrinth of corridors that might even have befuddled the Minotaur, but he found his way up to Stacy Donnelly’s room with few wrong turns. Destiny.

She lay on the far side of a semiprivate room, one of hundreds of such sterile quarters in this place of life and death. He passed an unknown girl sleeping in the first bed, was then facing what had become of the lovely woman-child he had met yesterday. She lay on her back, swaddled in bandages on her limbs, around her head. A few ugly lines of stitches crosshatched across swollen bruises, so purple, so black. Her right leg was sheathed in a cast molded from hip to toes. A smaller one covered her left forearm. IV lines plugged into her arms, and she was mercifully asleep. Just as well. The only thing of any possible enjoyment here were the flowers, and they were plentiful.

His arrival woke a woman propped into a chair in the opposite corner. Blonde hair cut nearly identical to Stacy’s, and fuller hips. He had no doubt but that this was her mother. Too aware of that timeless competition, the mother who fears the loss of youth, the daughter who embodies emergent vitality and sexuality. The love-hate so strong between them, the agony and the rapture.

She blinked at him in brief puzzlement; probably thought him younger, given these clothes. “Are you one of Stacy’s friends?” Her voice was fuzzy from sleep, poor sleep at that. “I don’t recognize…”

Paul shook his head, barely spoke above a whisper. Hospitals and museums and libraries, do not disturb. “No. I just met her yesterday. At the broadcast. I was …” Oh go on, say it, don’t be a wuss. “I was one of the deejays there.”

She let out a pent-up breath, regarding him with newly awakened eyes that frosted over even as they sharpened. He could easily guess the label she now applied. He was no longer an individual. Now he was someone connected in an official capacity with the tragedy.

Yeah, Mrs. Donnelly, I guess in a way it’s my fault that your daughter’s in here. So if you want to blame me for it, okay, go ahead, but please don’t say it out loud. Not today.

; “How is she?” he asked.

“She’s been better,” and her voice could hold every bit as much frost as her eyes.

“Is she going to be okay?”

“Yes. But good as new? They don’t know yet. She was a dancer. A very good dancer. She wanted to make a career out of ballet. Do you have any idea what compound fractures can do to a dancer’s leg?”

He bit his lip. Steady. “I’m sorry, Mrs. Donnelly. I just wanted to see her for a minute, and then I’ll go. I promise.”

“Yes, I wish you would.”

Venom in his ears, Paul tried to shut her out for several moments. With her eyes of ice and voice to match, she was too much of a distraction. Yet she was also a catalyst, these psychic accusations bringing him into closer contact with the deepest parts of himself, the parts that hurt because Stacy hurt. The brotherly love he knew he should feel for anyone in this situation.

He stood along the right side of Stacy’s bed, and it seemed almost predestined that her right arm was little harmed. That the cast was on her left. Her good hand lay by her side, atop the sheet, two scant inches from the low stainless-steel retaining rail.

Letting his own hand creep forward, upward, Paul reached between the rails. The angle was so discreet, he didn’t think Mrs. Donnelly could see him doing so. He loosely clasped Stacy’s small, cold hand, recalling what had at the time been one more crazed inspiration to entertain the listeners of KGRM. Last Thursday morning. Laying hands on the terminally stuffy Peter Hargrove, casting out the demons of summer colds. For laughs.

Peter’s voice, newly clear: I do believe you cured me.

He had thought at the time that Peter had steamed himself open with the heat of a full-blast shower. Except there had been no relapse, no return of congestion, no more sneezing. Ever.

This was insane, it couldn’t work, he couldn’t just hold her hand and expect her to get better. But he waited a moment, watching carefully…

And was absolutely right. Nothing happened.

Damn it. Deep breath, hold, release. Well, now wait a minute. Of course results weren’t going to be forthcoming if he stood there and didn’t even expect them.

After all, even though last Thursday’s ceremony had been strictly for amusement, a certain part of him had nevertheless taken it seriously. Not out of any hope of succeeding, but simply because he had thrown himself heart and soul into the moment. Playing the part. Feeling it. Doing it. Method radio.

So let’s play it again. For real.

With the focus of a surgical laser and the broad pattern of a shotgun, Paul gripped Stacy’s hand a little harder. As if by doing so he might reach back through time and yank her from the tan car’s path, to safety. He pictured his failure to do so, mentally retracing her arc through the window at The House of Wax. Summoned up the prone, twisted image of her lying amid the glass wreckage.

And now, now, he could feel her sorrow of dreams ruined, her dancer’s leg pierced with nails of bone. His own sorrow at having let it happen.

Paul knew virtually nothing of her, little beyond her energy, her beauty, her spirit. Her love of life that had been apparent to anyone with an ounce of perception. This much he knew. He knew her name. He knew her pain. Apparently these were enough.

The empathy was astounding. He could feel the subtle energy coursing between them, generated from some emotional turbine he had never known he possessed. Cranking tentatively at first, as if its parts were corroded from disuse, then more freely, oiled by the misery of having had secret dreams of his own dashed to pieces this morning. He could feel the turbine spin, whipping their separate agonies into a single pure blend. All flowing into him, because for now, he was by far the stronger of the two, and he would help her shoulder this immense burden. Carry it the first mile because she needed it, the second because he wanted to.

Paul felt no extra heat radiating from his touch; her hand remained cool. No matter. Whatever he felt was working on the inside, where it counted. Bone cells regenerating, knitting together into a pillar of strength on which she could once again stand, leap, pirouette. Leukocytes massing into inner fires to burn out the infections. The adrenal surge of healing, a steady erosion-in-reverse working its way up through the layers: striated muscle, lower dermis, fat, collagen, corium, epidermis. Lacerations sealed and paled under their stitches and bandages to become ghosts of their former selves. Her sleeping mind shifted suddenly into the REM state, to gift her with a wondrous dream of benevolence personified, reaching down to touch her.

He seemed to instinctively know when it had been enough, and slid his hand out of hers.

It no longer mattered that Mrs. Donnelly still looked daggers at him, that his resting heart rate had soared to more than a hundred beats per minute. For he was jubilant within, soaring and weightless and free, I did it, I actually did it, and exactly how or why seemed far less important than the simple fact of its being. He had controlled it, made it work at will.

And she’d slept through the whole thing. Not that he had expected her to pop up and crack open the casts like the eggshell of a newly hatched bird. Too melodramatic, he didn’t want that. Better this way, quiet and unobtrusive. For he hadn’t turned back the clock and made as if yesterday had never occurred; he’d only repaired the damages. She would remember, and she would hurt, with soreness and stiffness to work through, and strength to regain. But he had bought her the chance to do so without the accompanying heartbreak of a less-than-complete recovery at the end of that road.

“Sleep well,” he whispered, then bade a quiet good evening to Mrs. Donnelly and returned to the hall.

A jaunty stride down the corridor, so far removed from the trepidation with which he’d arrived, past nurses and patients and visitors alike. Infused with energy, enthusiasm, a big stunned grin breaking out across his face — oh, tonight he would rejoice. Tonight he would howl in celebration as old as time.

But not yet. Not yet. This night of glad tidings had just begun, and there were seven other kids out there who deserved a visit.

He would not disappoint.

2540 B.C./Sumerian city-state of Uruk

So. The path of civilized men who tilled the soil to reap its bounty, who built monuments toward the skies, had led to this.

The scribe watched the procession wind through Uruk’s dusty streets, above it all, standing just past the doorway to the temple of Inanna. City guardian, goddess of fertility, goddess of love. She, who had in the Days Before Men decided that her city would be the greatest center of culture in all of Sumer, in all the civilized world. She, who had brought them splendor, glories beyond counting.

Yet other divinities lived, gods and goddesses, some of whom were hungrier. Unsatisfied with fearful worship and appeasement in spirit, they wanted more. The scribe had fiercely hoped that Inanna would intercede on Uruk’s behalf, make her objections known to the priests and priestesses who had decreed the fate of the four wretches now wheeled through the streets.

But neither dream nor whisper, neither omen nor divination. Nothing. She kept a silent tongue. Very well, then.

He was Annemardu, chief scribe of the temple of Inanna, overseer of all scribes who recorded temple business. Inscribing hymns and letters, accounting for the holdings and transactions of grain, livestock, land, more. In centuries past, such need had driven the Sumerians — the black-headed people — to develop a system of permanent record-keeping, the invention of the written word. Cuneiform, wedge-shaped characters etched by a carved reed stylus onto tablets of clay.

Of its lasting significance, Annemardu had but the vaguest of notions. A practical solution to a problem, that’s all it was. Just like the round wooden wheels devised so that donkeys and oxen could more easily pull grain carts. Just like the fields that once were arid desert, here in the Land Between the Rivers. They were now irrigated with a complex system of canals and dams, water drawn from the natural levees built by yearly flooding of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

Man, he knew, was inherently no

more unique a being than the beasts of burden who helped the farmers till their fields beyond the city walls. No more noble than the feared lions stalking the reed marshes. Certainly man could not be the most feared creature that walked the earth. As a young man, years past, Annemardu had seen a bone unearthed from clay in the marshes. Trembled at its size, the single bone longer than his entire body, and his imagination reeled in fear as to the size of the being these remains had come from.

What walked this land before we did? he’d wondered at the time, and since, had never stopped.

But of man — of themselves — there was no sense of awe. Yet on contemplative nights in his house, head swimming from the effects of the barley beer he bought in the city bazaar, Annemardu ventured to speculate if perhaps they might be wrong. What other animal could wonder what walked the earth before it? Even if it did, what other beast could give voice to the musings? And even if those animal bleats were understood by its fellows, then what beast could write them down? Something to consider.

Man, merely a higher form of animal? Perhaps. But an animal with audacity like no other.

Perhaps the inherent greatness separating man from lesser beasts, while good, was fraught with its own kind of perils. Great accomplishments could only be born of great passions, and great passions sometimes went astray to become great injustices. To live together, to work together, to divide the labors of daily life — these gave them all, from aristocrat to commoner to slave, a power unlike any other race of men. And with power comes pride.

Annemardu watched as the procession turned a corner, headed for the main gates in the city walls.

Uruk, for you, this day I weep.

The complex of temples — for Inanna, for An, for others — stood taller than any building in the city. The crown of Uruk, it was, vast tier-stepped structures called ziggurats, built from mud-brick in imitation of mountains. From the upper terrace, a temple worker could survey any and all of Uruk he or she pleased. Houses and public buildings, each built from the same bricks as the temples. This sea of mankind, the same hue as the desert, was interrupted by patches of greenery, landscaped public parks. Here and there were markets and bazaars, where merchants and traders sold meat and fish and produce, and goods made by local artisans or craftspeople from other Sumerian city-states, and even exotica from far-off lands. Linking all were gridded streets, and enclosing all were the walls of Uruk, straight and solid, as if the earth itself had risen up. These great walls and their nine hundred towers had been built the previous century by Gilgamesh, king of legend, hero among men, a god upon death. Beyond the walls, to east and south and north lay the fields and canals, suckling from the Euphrates. To the west lay the desert, dull brown wasteland without end. Here dwelled the utukku, demons of human suffering.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

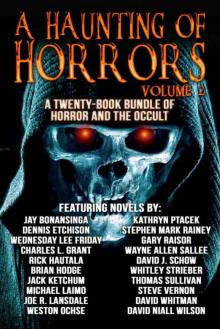

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

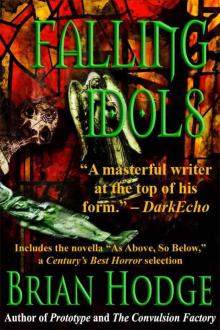

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols