- Home

- Brian Hodge

Prototype Page 13

Prototype Read online

Page 13

All in all, to Clay it served as no threat. Once or twice, at least, it was probably a good thing to have a relationship in which you knew you were just one more inserter on the assembly line.

She lay with him through the afternoon, warm company with whom to weather out the worsening assault of chilly rain at the window, and the continuous barrage of news from television in the next room. Daylight waxed and daylight waned, just that, just light; never a sun. She wanted to call the others, Graham and Twitch and Nina, let them know he had returned in one piece, but he said no, not today — what if they wanted to come over already? He had disappeared almost two months ago. The news would keep until tomorrow.

He showered when the road-worn feel of his skin drove him out of bed, for a time huddling on the slick and stained porcelain as water beat down upon his fetal body. A hot rain, but he shivered as if it were the cold deluge beyond the windows. Strange moments indeed: home again, setting his own schedule; in control of his life once more, if he didn't count the lithium. Although that was taking much for granted, and assuming he'd been in control to begin with. Maybe he never had been, and free will was the cruelest of illusions; every step he’d taken and decision that had seemed arbitrary might have been as predictable, to anyone who knew those inscriptions of nucleic acid, as C following B following A. A savvy fortune-teller of the genetic age might be able to divide his cranial lobes and tell all from simple inspection: Kick a man in the teeth even after he has been justly conquered? There, in that whorl of brain tissue. Carve a scar on his own arm? There, there, in that fissure…

For you are not like others

not like others

not like others

He left the bathroom, wrapped in a towel, his damp hair combed back, slick and contoured to his head. Erin was standing at a window off the kitchenette, watching sluggish traffic on the street, when he came up behind her.

"Stitches, too," she said upon turning to see what the bandage had been covering earlier, fingering the knotty black line over his eye. Starting to laugh, then, supple mouth breaking into a smile beautiful in its sadness. "You look like they gave you a lobotomy."

"It might be the only way to fix things," he said, half-joking, and despite the serious half he realized he was almost happy like this. The two of them standing here, it could be mistaken for something normal … rainy Sunday afternoon, what do we do now? Someone peering in from the other side of the glass might even get the impression they were in love.

"They found something genuinely wrong with me," he began, keeping his earlier promise, and he told her. It came surprisingly easy; it sounded like such a joke. Sum it all up in a few brief sentences, and what did it make him, if not a punch line to some evolutionary jest? Somewhere even now Darwin might be laughing.

Eye-to-eye, she did not blink as she held his bare shoulders, biting her lip. Better she ache there than within, right?

"You're so alone," she whispered, "you are so alone. Always have to do things your own fucking way, don't you?"

Clay did not know what to say to that, had no arguments, no evidence to the contrary. So he just watched her shake her head and roll her tongue inside her cheek until she sagged, resting her brow against his collarbone. One wandering hand debated where to alight, trailing from his arm to waist to leg, finally fumbling beneath the towel and cupping his genitals. He grew against her, and shut his eyes as soon as he felt a tiny trace of moisture against his chest. If she had shed a tear for him, it was nothing he wanted to know about, nothing he could afford to know about.

Erin took the lead in making the way to his bedroom, lay him down on the bed while whipping her own clothing aside: oversize black T-shirt, tight black leggings, black Doc Martens boots, flung into a pile like an exoskeleton. Her every rib was clearly defined, her shoulders as bony as a waif's, although for someone so skinny she was uncommonly large-breasted.

She straddled him and leaned forward along the length of his body, kissed his lips, but with his tongue seeking to probe deeper she pulled away — up, then, to his brow, where she settled her mouth over the stitches. The knot was still exquisitely tender and as sensitive as an erogenous zone. He could feel the tip of her tongue play across the needlework, then a faint teasing pressure from her teeth; strange game of trust, this — he did not wholly feel secure that she wouldn't bite down hard.

In the back of his mind he longed for a condom, but she would not want one. She played that game of roulette in her professional life; her personal was but an extension. It wasn't even so much that he worried about diseases as it was the risk of failure of her birth control pills. What a horrible thing that would be. She could abort, but their child might truly be its father's, consumed by fierce survival instincts; it might fight the scraping and the suction, turn her womb into a battleground. He had always been averse to the idea of bringing a child into the world, even more so now that he knew he was wrong on a molecular level. A second generation might be more hideous still, like every parent's curse become prophecy fulfilled: Just wait until you have a child of your own someday: then you'll see.

He gambled again; parted her and entered unguarded, the fear a dark and shining facet of the thrill.

Erin shuddered upright, then bore down upon him with a face he had never seen in her still-life faux sensuality. She looked wounded, angry, capable of consuming him; then she doubled in on herself. She stretched back, back, reaching to the foot of the bed with long thin arms and bringing the video camera to her eye. Red light winking on; she flexed her hips, seeking a rhythm at last, and the frame would have a steady rolling flow.

Selfishly, he missed her hands on him, their rough urgency, and her eyes were gone, replaced by glass and plastic and metal, so he shut his own, and concentrated on trying to feel what he could, whatever he could. It really was better this way.

Fourteen

Early Monday morning, Adrienne began setting appointments to see condominiums for an indefinite rental. Her criteria were few but inflexible: The place would have to be fully furnished; it would ideally be within a mile or two of Clay's apartment, to facilitate contact; and it would need, if not a room, at least a corner or wall that she could rearrange to her liking into some semblance of a professional domain. Better for both her and Clay if they had a territory to help ease them away from the Tempe office to which they'd been accustomed.

She kept her first appointment later that same morning, with another for late afternoon, a third for Tuesday. After lunch, she whittled away a couple of hours going over notes and the Helverson's case studies.

Anything to put off taking the actual plunge? Maybe she was stalling. Once she picked up that phone and resumed contact with Clay, the pressure to perform would begin from all sides, with no one to fall back on. Her isolation had become a tangible essence, she was bathed in it. Even Sarah's eventual arrival — whenever that occurred — would be more tonic than cure.

She placed the call, imagining that Clay would not answer, that the number he'd given was a decoy and the apartment not even his; he would have given them all the slip as he straggled off to some other desert of scorched revelations. She would return south in failure and disgrace.

And when he picked up on the other end, she felt quite the irrationalist.

"How are you feeling?" she asked. "This isn't too early to call, after all, is it?"

"No, no. I'm fine. I've slept a lot, but I think I'm coming out of that today."

"How is it to be back home? Any feelings of dislocation?"

"A few," he said, a reluctant admittance. "Even though I didn't much care for it, I got used to a routine in that place and it's not in effect anymore. I keep expecting people to come in to look at me, and they don't."

"It's normal, trust me. Clay, Friday morning you woke up on Ward Five, the same as you had every morning for a month and a half. This is only Monday. If you still feel this way in a week, let me know. But I doubt you will."

"I don't miss them," he said. "And it's good to get

back to an irregular meal schedule."

Adrienne had him grab a pen and paper and take down the hotel phone and her room number, told him she should be there until the end of the week, give or take a day. She didn't think they should wait for her relocation to resume sessions. Had he given any thought to a schedule he might like? Sundays and Wednesdays were good enough before, nothing wrong with them now, he said.

"Then I'll expect to see you day after tomorrow," she said.

"Listen, if you're interested … three or four people I know, they wanted to welcome me back tonight, at this place we go. If you want to come…"

Her immediate impulse was to decline. He was a patient; it was not a good idea to socialize with patients. Then she amended: He was far more than that, as her duties had for the first time been extended beyond therapy into field observation.

You're in my world now, he had told her. I'm not in yours.

"What kind of place are you talking about?"

Clay seemed to consider this for several moments, perplexed or at a loss, then asked, almost cheerfully, "Have you ever read Dante's Inferno?"

*

The Foundry, it was called. She had said she would try to make it by ten, after the others would have been there an hour or so, but decided it wasn't so bad to be fashionably late, however unwittingly.

She fought the urge to take a cab — better she learn to get around without a hired crutch. Circling the blocks in an area north of downtown to which Clay had directed her, where the buildings looked grained with decay, where storefronts and their roof lines defiantly stood despite advancing age, as if proud of fatigue and scars. Doorways and windows frequently wore faces of nailed plywood, never blank, bristling with bent-cornered flyers and thousands of staples, layers upon layers of each.

She parked, finally — perhaps the place she was looking for was invisible from a car — trying to walk these streets as if she belonged here, knew them by heart. At last she came upon a sigil: The Foundry, in black spray paint on raw brick, nearly invisible in the night, on the flank of a building just inside the mouth of an alley. An arrow pointed back. Not a place you would stumble upon by accident.

Descending to a doorway below street level, she paid the four-dollar cover to a boy with blond dreadlocks, greenish in a spill of light from within. Without checking her driver's license — how depressing, her youth must really be gone forever — he sealed a cheap vinyl bracelet around her wrist and she was on her way. The music was already rumbling out at her, louder with every step along a concrete corridor that felt thick underfoot, sticky, like an old theater's floor.

It took her into a low, cavernous asylum of a place — bedlam's basement — where heavy-gauge pipes ran riot along walls and the ceiling. Here and there some fetish dangled; mutilated baby dolls were popular, charred with a blowtorch or skewered by spikes or garroted with frayed wires, shining sightless eyes, invariably blue, wide with naiveté. A pair of projection screens unspooled a continual flood of imagery — one a horror film, the other what appeared to be a narrative-free video collage of everything from medical procedures to wartime-atrocity footage to factory machines disgorging glowing rivers of molten iron — but no soundtracks could be heard above the music. Much pandemonium on the dance floor, as heavy bass tones shuddered into bones and a caustic treble grinding rended equilibriums in a corrosive symphony of deconstruction.

Seating was confined along the walls, discarded cathedral pews and tables and chairs imprisoned in alcoves behind chain link fencing. It was in one of these that she found them, Clay her one and only clue. He stood when he saw her, laughed at the look on her face.

"Toto," he said, "I don't think we're in Kansas anymore."

"I'm more used to coffeehouses at home." An idiot confession. A college town, surely Tempe had someplace like this, but she had no idea where to find it.

Three others sat at the table, eyes neither welcoming nor rejecting her, more curious than anything. They would surely know what she was, if not every detail as to why she was here. She guessed that she was older than most by eight or ten years, maybe more in the case of the thin blonde to Clay's left, but it did nothing to alleviate the sense of intimidation. The world often aged people by pain rather than by years, and if their families had been anything like Clay's, she could well have walked in upon a conclave of ancients with deceptively young faces.

She sat, and Clay made cursory introductions. The thin blonde to his left was Erin. At the end of the table was Graham, another stick figure lost inside a T-shirt — didn't these people eat? — who met her eyes briefly, then averted as he took a draw from a cigarette pluming with some rank herbal smell.

"Clay's mentioned your paintings," Adrienne said. "I'd like to see your work sometime."

Graham nodded, and with one bony, large-knuckled hand waved out toward the dance floor, the ceiling.

"The dolls?" she guessed.

He nodded again. "They aren't supposed to be anything, I was just bored one night."

"But the material just happened to be sitting around," this from the chunky young woman across the table, with thick, red, wavy hair, an obvious dye job, gathered to one side in a kind of gypsy scarf. Clay introduced her as Nina.

"Look close now, she'll probably look completely different next week," he added as a caveat.

"Piss off," Nina told him, not unkindly.

"I'm just letting her know you keep a frequent metamorphosis schedule, I'm not saying there's anything wrong with it." Turning to Adrienne, "Uncle Twitch works in the sound booth, maybe he'll be out later." Clay pointed across the dance floor, where brutal silhouettes collided under blue-purple lighting. A small structure appeared to cower in the far corner, behind another barricade of chain link fence, beneath lights and speakers.

"Would you tell me if you did think there was something wrong with it?" Nina asked.

"Yes," Clay said without hesitation.

She leaned forward to seize Adrienne's complete attention, as if it were suddenly very important to explain herself. She seemed to crave intimacy and there was no way intimacy could be achieved with the volume of the music, with the exaggerated gestures required to compete.

"I just don't think anyone should limit herself to only one incarnation, that's all," she said, nail-bitten hands flailing in tight circles. "What if I like myself even better another way? How can I know unless I try it?"

"I understand." Adrienne tried to nod with reassurance. Poor thing, she knows what I am and she's afraid I'm going to pick her apart right here at this table. "I live with someone who's the same way about a lot of things. She has trouble making up her mind if it means excluding some other option."

Nina began to nod right along with her, wide pleasant face radiant with proxy kinship to a nameless stranger — yes, that's it, exactly.

"A few weeks ago she asked if it was her fault that everything looked so interesting. It stumped me."

"And by living with her, you mean…"

"We sleep in the same bed, if that's what you're getting at."

"That's cool," said Nina. "I tried sleeping with other women but it just didn't work for me. Hetero and hopeless, I guess."

Graham, his face high-cheekboned and oddly aristocratic, blew a dour gust of smoke. "I'm sure you can find a support group somewhere."

"Piss off," she told him.

Graham pushed black, tumbledown bangs from his eyes, flashed a look of impish mockery at Clay, then back to Nina. "I'm just letting her know you're a neurotic flake, I'm not saying there's anything wrong with it."

Nina drew back in indignation. "Graham, I hate to tell you this, but you're an asshole tonight."

Erin propped her chin on a fist, looking down at the table, and said, "A lot of that going around lately."

Nina had recovered quickly, leaning toward Graham with forces marshaled. "Some people think change is healthy. Some people" — a glance toward the sound booth — "find change sexually arousing. Every few weeks or so, Twitch gets to ravage

a new woman and we don't have to worry about disease entering the picture."

Erin looked up, interest renewed. "This is a good time to ask something I've always wondered. What if Twitch likes ravaging one of the earlier women better?"

"Well you can just piss off too," said Nina, and now she really was beginning to get agitated.

"What, what did I say?" Erin cried. "It's a valid question."

"Well, it doesn't deserve an answer."

Graham nudged Erin's shoulder. "It's already happened," he declared, very sure of himself, and did not give Nina a chance to respond. "Which one was it, let me guess: the dominatrix? Or was it the post-Woodstock earth-mother with the Birkenstocks?" A shrewd smile, a carnivore's smile. "Which one moaned louder?"

"Graham — "

"And does he ever breathe a sigh of relief when one's gone?"

Nina drew back in her chair, seeming to shield herself behind the scattering of empty bottles, bleeding from unseen slices. Eyes that moments ago had shone brightly were now dismal and frantic, without grounding. She looked to Clay but got nothing. To Adrienne it was like watching someone being poked with a stick, seeking support from an older brother, and finding only a turned back.

Save for Clay, she did not know these people, but could she sit there and let this happen? Say nothing? Would they even listen to her? She had stiffened in her chair, and before she could say a word, it was as if Clay knew precisely when to nudge her arm.

"Come on," he said, "let's go introduce you to Twitch."

Staring, torn, I'm needed here —

More insistent: "Come on," voice low and compelling even through the ratcheting music. She followed him out of the cage into greater light, denser sound, a disorienting assault. She pulled in closer to Clay, her mouth at his ear.

"You could have stopped that, couldn't you?"

"Probably," he shouted back.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

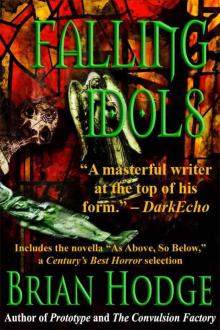

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols