- Home

- Brian Hodge

Prototype Page 14

Prototype Read online

Page 14

"But you didn't."

"It'll stop anyway."

Why, you cold prick — it crossed her mind before she was able to filter it out. Objectivity had died without a whimper. What a plunge this was, ripped from the four safe walls that comprised her zone of efficiency in Tempe, set down where she wasn't even sure which rules had flipped. The dynamics of exchange were completely different here.

I am a fraud and I'm totally unqualified to be doing this. The sudden need for Sarah swept over her. Sarah would lead by example. Sarah would thrive here, would have immersed herself upon arrival. Sarah would take to them naturally because that's what Sarah did, and in that moment the only thing that terrified her more than Sarah deciding she should stay home after all, was if she came, and the rest of them, Clay especially, decided they had no use for Adrienne at all.

Clay in the lead, they weaved through the throng of long hair and shaved heads, leather and flannel, T-shirts and dark wraiths, all of them like members of allied tribes who had come together for noisy ritual, drawn by a summons they may not even have comprehended. They were in here, they were not out there, and it was enough.

He first led her to the bar, where she got a gin, and he some red-orange concoction in a plastic glass. A smart drink, he told her: quantum punch.

"Much alcohol at all, it just kills me," he said. "They say this has amino acids, it helps your brain." Taking a drink, then shrugging. "Probably just bullshit."

They circled the floor again, a slow path. On one screen, actors in latex demon makeup menaced a young woman with curved tools of butchery; on the other, a mad-eyed rhesus monkey secured by metal clamps shrieked without sound during the advanced stages of vivisection. She turned her eyes away, the symmetry obscene.

Clay halted at one point, tried to explain that Graham really didn't intend to be cruel to Nina; it just came out sometimes when he had been drinking. His own theory: Graham secretly envied her apparently effortless flexibility. He had his paintings and an occasional sculpture, but these were all he dared try, while Nina was essentially fearless. She constantly attempted to define her own niche, without much success at anything, but at least she tried it all. Painting had been an early experimental passion, but Graham had laughed off her vision and execution as immature, so into the closet it all went. Last year she had tried writing subversive children's literature, not disliking children but resenting them for their innocence, and had penned such twists on convention as The Little Engine That Died and Little Red Riding Crop, in which Red seduced the wolf and found him to be a closet submissive; but no one had cared to publish them. A few months ago she'd tried her hand at designing greeting cards for people who hated holidays, hoping to market the idea of a series of Sylvia Plath Christmas cards, but had been denied the rights to reprint excerpts from the selected poems.

Meanwhile, Graham had his paintings, and did not even feel comfortable straying from the corroded iron realms he had forged for himself.

Of course not, thought Adrienne, he's painting his own prison, a hasty judgment considering she had only heard the works described and had barely even spoken to him; but instinct was often more correct than she gave it credit for.

"Nina," said Clay, "she'll probably outlast us all."

They worked their way around to the sound booth, and Clay rapped at a plastic window overlooking the dance floor, showed his face, then they moved around to a door that looked flimsy enough to withstand one kick, no more. After a moment it was unlocked, and they squeezed into the booth, at most four feet by eight. The volume dropped immediately; you could converse in here without throat strain.

A tall figure was hunched forward, feverishly loading music, a mad Frankenstein busying himself with digital technology. Even alone he would appear too cramped in the booth, the sort of guy whose elbows and knees seemed to have their own renegade senses of direction. A short sandy ponytail hung limp at the nape of his neck, and he wore a beard but no moustache. To Adrienne he looked like a young Amish man gone irrevocably astray.

"Charmed," he said flatly when introduced, and shook with a hand already burdened by a cassette. He missed not a beat and prattled on, ignoring Clay for the moment and talking only to her. "Look at these, would you?"

He forced upon her the cases from two compact discs and one tape, releases by artists she had never heard of: Godflesh, God's Girlfriend, the God Machine. Adrienne gave them back with a vacant smile, much like her own mother's when she had been handed some cryptic crayon drawing: Oh yes, isn't that nice.

"I come up with these thematic blocks, and nobody out there ever catches onto them." Uncle Twitch looked disconsolate. "No one recognizes subtext anymore. I work among philistines."

Adrienne glanced at the two windows, long and narrow and overlooking the concrete dance floor like gunports in a fortress. Beneath them were makeshift shelves for the CD players, a tape deck, a turntable, a mixer, the amplifier. She looked for someplace safe to rest her glass but there was none.

"I'm sorry," she said. "Maybe there's no incentive to tell you."

Twitch looked at her, open-mouthed and perfectly still, then nodded sharply. He reached up to seize a microphone and lever it down before his face. Flipped a switch and his voice cut in over the music like that of an angry prophet: "The first one of you ungrateful cocksuckers who can tell me what the last three tracks had in common gets a free rectal exam!" He jammed the microphone back into place and crossed his arms. "There."

"Subtle," said Clay.

Cheers and jeers from the dance floor; from some unseen quarter most of a cup of draft beer came showering across one window, and Twitch cackled loudly. "That got 'em! Sometimes you just need to know you're not being taken for granted."

He settled, finally looked at Clay. Warmly, she noticed, a small smile creeping onto the corners of a mouth that looked given to smiling frequently, almost against its will.

"I'm glad you're back," he told Clay, lightly, though not without concern. For a moment Twitch looked as if he intended to hug him, then consciously forced it away, as if even an arm tossed about Clay's shoulders for a few seconds would be too much, either feared or unwanted. Worse, it appeared mutually understood.

Here they lingered, the booth calm and cool, a hurricane's eye in fragile isolation from the chaos just yards away. While Clay and Twitch conversed, she remained at one window, a staring face washed black and blue and purple, the colors of fresh bruises. She could watch with more removal than she could ever have summoned at one of the tables; out there a patron, in here an interloper who watched dancers that did not so much dance as spasm, less from celebration than the vaguest kind of rage. The music was well chosen here, the sound of a world grinding its children into grease to lubricate its machines. Here the defiant could stave off that fate awhile longer; or maybe they mocked it, or simply rehearsed the moment when they too would be fed struggling into the maw, like their parents before them. Or perhaps they worshiped it instead, without even realizing; gods took many forms, and the new ones were no less thirsty for blood than the forgotten ancient deities; they just waited until it was spilled in newer ways.

Clay decided to leave the booth long enough to return to the bar, and she decided against following, risking the impression she was dogging his every step.

"He told us," said Twitch, soon.

"Excuse me?"

"About being a freak."

Adrienne turned from the window. "That's not the terminology I like to use."

"I think he prefers it."

"And I don't."

Twitch nodded with appeasement — not worth arguing about. At once she found something endearing in his clumsy way of trying to steer out of this.

"He can be so honest about himself, in the strangest ways," Twitch mused, hands moving restlessly over knobs and switches and sliders, as if they found comfort there. "Is it … is it dangerous for him?"

Adrienne sagged, hands in her pockets. "I can't answer that. I wouldn't if I could."

"

He thinks it is. Isn't that all that matters?"

No, but that was most of it, so much so that there was no need to refute. Clay was back soon, spent a few more minutes in the booth before deciding to return to the table. She came along this time, eyes drawn to the reality screen in spite of herself, where a man sat placid and shaven-headed, eyes catatonic, while doctors probed into his opened skull; one cheek ticked as if jerked by a puppeteer.

At their table they found that Erin had left for the dance floor, while Nina sat holding a morosely stupefied Graham as he sagged against her side. His expression looked like something that someone had crumpled up and cast away. He might have been crying recently, or not; most certainly he was drunk beyond repair. And Nina, eyes full of pity, as if she was not sure what else she could feel … she held him, and kissed his forehead, and brushed the hair from his eyes when it fell there. Whatever she whispered into his ear was lost to the greater din.

Clay nudged Adrienne’s foot to get her attention.

"Told you, you're not in Kansas anymore," he said, and drew out a chair and sat heavily upon it, to wait … until, she supposed, the night ended.

Fifteen

Quincy Market was one of Boston's main melting pots, and that was why Patrick Valentine loved it so. It was more than just the food, although that was incentive enough. Here, all the cuisines of the world converged, small counter stands packed along a gray stone hall that looked more suited to housing a wing of government. You could walk from end to end, side to side, slowly, taking time to breathe, to savor, and conduct a global tour via aromas alone.

Or you could sit and watch the passing humanity, and the world would come to you. He knew of no place else where he could see such diversity among those with whom he had to share the planet, and it always did him good to keep in touch this way, keep him mindful of why he was what he was.

Sometimes he indulged fervid old fantasies, imagining the break in the humdrum that he could bring to the herds who came to feed with firm belief that the day would be a day like all others. How many could he kill in, say, five minutes of forever? He was a man who knew weaponry, who had made it his business, and his hands seemed made to hold it. His fingers and palms fit machine-tooled steel as the hands of passionate men fit their lovers. With the compression of one index finger he could awaken them all from their walking comas, and bring home to them the truth of the world, and worlds beyond: All things tend toward entropy.

But not today; not ever. How he had managed to quell such impulses as a younger man remained elusive, but mystery augmented relief; surely some greater process had been at work to stay his trigger finger. Ignorant of his heritage then, and now wiser by extremes, he had a greater purpose, the best kind: one he had created for himself.

A Thursday afternoon; alone, then not. The man who joined Valentine at his table brought with him the scent of a shivering city and breath that smelled of cherry throat lozenges.

"Are you eating today?" Valentine asked him.

The man coughed into his fist and shook his head, eyes red and watery as he tried to smooth his graying, gale-blown hair. He owned, by many accounts, one of the finest minds in a city filled with exceptional minds, but publicly downplayed it well enough. Stanley Wyzkall may have been the director of applied research in MacNealy Biotech's genetics division, but it was possible that rumors were true: His wife was in charge of his wardrobe.

"Something to drink, then?" Valentine asked, and Wyzkall told him a hot coffee would be nice. He left to patronize a Greek vendor, souvlaki for himself and coffee for them both. When he returned he found a fat manila envelope waiting on his side of the table, and it was just like Christmas, six weeks early.

"Hello, hello," he said to the envelope, snatching it up. Papers spilled into his hand but gold dust could have been no more welcome. Medical profiles, psychological evaluations, MMPI results, subject's history … enough to keep him engrossed for hours.

"Quite the unique extended family you've grouped about yourself." Wyzkall honked his nose into a napkin before bringing the coffee to his lips, two-handed.

"And he actually consented to continued observation," said Valentine, still scanning pages. He then crushed them to his chest in the closest thing to glee he could feel. "Maybe there is a God."

"Mmm. Possibly. But defined by a keen sense of the absurd, wouldn't you say?"

"I wouldn't call it perfection." Valentine stuffed the papers back into the envelope, too much of a temptation — his lunch would grow cold.

"The attending psychologist — Rand is her name — has been in Denver since last weekend. She returned him there herself. She's agreed to file weekly progress reports with Arizona Associated Labs. Of course I'll have access to these. And this, mmm, this brings up the matter … the matter of — " He began to clear his throat harshly, at last popping another cherry lozenge and looking so reluctant that Valentine was tempted to just let him squirm.

"The matter of a weekly retainer?" he prompted.

Wyzkall appeared greatly relieved.

"How much?"

"Twenty-five hundred per week seems reasonable."

"Two thousand is the limit at which I'm prepared to keep from being unreasonable." He hunched forward, bringing his face closer to Wyzkall's, every sweeping curve of his skull glistening with intent. And his eyes, cunning eyes, flat eyes that spoke of pain for the sake of expediency, that simmered with the knowledge of families who should be protected from assassins unknown. There was no need to say another word.

Because you trust me and I trust you, ethically and legally and in our future goals we have each other by the balls, but you always keep that little flame of fear of me alive. Because you know what I am inside and there's always the remote chance I may explode in your face. You have dealt with a devil and he pays you well, but the devil can always, always, slip his leash.

"Two thousand will be sufficient."

Valentine settled back into his seat. He bluffed well but would never hurt Wyzkall. You did not hurt the goose that laid the golden eggs; although if you could scare it into shitting out a little extra gold now and then, so much the better.

"Drink your coffee, Stanley," he said, "and we'll decide the best way to launder in the new cash flow."

*

Theirs was a business relationship based on the two primary commodities in the modern world: money and information. Over the past four years, Valentine had paid $20,000 apiece for his own copy of the file on each identified Helverson's syndrome subject. He had an insatiable need to know the limits of the mutation that had marked his own chromosomes; the private sector lab for which Stanley Wyzkall served as research director had an equal need for monetary reserves.

MacNealy Biotech, in addition to its indigenous research projects, was one of numerous labs the world over involved in the Human Genome Project, the inner-space equivalent of landing the first man on the moon. Discussed in think tanks and on scientific symposia for years, and finally decided to be technologically feasible, the Project was launched in the fall of 1990 with the fifteen-year goal of mapping every strand of human DNA. Each of the three billion nucleotide base pairs, charted. Each chromosome identified, its function labeled.

The resource needs were staggering. Entire supercomputer data banks would have to be constructed to contain the sequenced information. New technologies needed refining to speed up the process of deciphering the protein codes. Human effort was estimated at upwards of 30,000 man-years of labor. And the financial requirements would be almost endless.

Patrick Valentine felt that, in some small way, he was doing his part. Stanley Wyzkall wanted none of the covertly allocated funds for himself, instead insisting they be directed, through foundations that existed only on paper, into MacNealy Biotech.

It all worked out well, and shaped direction in a life that had for its first forty years seemed to him to be absolutely without meaning.

Chicago-born, Chicago-bred, Patrick Valentine had grown up, if not the toughest boy i

n his surrounding neighborhoods, at least the fiercest. His furies knew no logic, they were just there, so much a part of him that childhood acquaintances who committed no mayhem seemed another species entirely. Life was something to be consumed, not savored, then shit out as quickly as possible. Years of turmoil and restless energy and a formless anger had brought him nothing but welts across the back from a distraught father who continually threatened disavowal, and a succession of run-ins with the law.

What a strange, strange lad. What a disappointment. He was educated, but not civilized. He looked in the mirror and saw only the dimmest capacity for greatness, buried in the roughest ore.

Great men must first become great masters of themselves, and connections eventually formed in his mind. The blue uniform that had heretofore meant only trouble gradually took on an air, not of mystique, but of practicality. Here was a channel for his violent exuberance. Here was a job he could love.

The Chicago Police Department was a most unexpected choice to those who knew him.

He applied. He was accepted. He was amazed.

The feel of the baton, the comforting weight of the service revolver … these became extensions of himself. They were the distillations of potent rage given a vessel to contain it. That he represented law and order was incidental. Far better was that he had been given both a license to inflict controlled miseries upon those whose word could never stand up to his own, and a support system that backed him up when there were doubts. Valentine knew no fatigue when it came to subduing the guilty with bruising ferocity. He was respected by some, reviled by many, and feared by all, but the opinions of others had always been of low priority.

Six years it lasted, this urban bounty of bleeding heads and broken bones, cowering lowlifes and intimidated lovers. Six years before termination for repeated use of excessive force; you really had to be a monster to get the pink slip from this outfit. He tried to take the turn of events philosophically — only so many complaints could be lodged before the scales tilted inevitably against him. He'd had a fine run.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

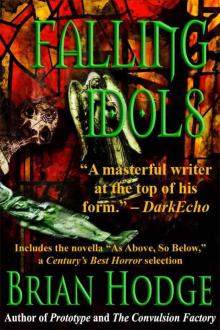

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols