- Home

- Brian Hodge

Prototype Page 15

Prototype Read online

Page 15

As well, he had long since taken measures to ensure a bonus to his income, a supplement with the potential to far surpass any paycheck the city of Chicago would ever cut him.

He had found the streets and weedy lots and decayed tenements to be a blue-steel cornucopia. Guns were everywhere, yet it seemed there was no end to the demand — a fine paradox. No gun made it to the evidence room if it could be avoided. Even those that did were occasionally misplaced. Shakedowns of suspects led to confiscations, as easy as picking apples from a tree.

It was a good racket. Investment was nil; the proceeds, 100 percent clear profit. His day job was such that he was in frequent touch with those who made the best customers, and some of them led him to connections greater still. By the time Valentine was fired from the police department, he was already masterminding break-ins at National Guard armories and manufacturer warehouses to truck away heavyweight hauls. Within another three years, he was plugged into an underground pipeline capable of supplying demolitions ordnance, rockets, mines, mortars, nearly everything that dealt a lethal blow short of nuclear.

Eternal demand, infinite supply. He had stumbled upon the one business that remained untouched by the whims of fickle economies. So long as one took precautions to avoid federal scrutiny, it was a seller's market. The groups all but lined up and took numbers: slothful insurrectionists and supremacist militants, international terrorists, private mercenary armies out to create third-world bloodbaths, and, after he had relocated operations to Boston, the IRA.

He took no sides, took only the rewards, but even the money paled beside the hypnotic thrill of tuning in news footage of some trouble spot in the nation or halfway around the world and knowing he might have contributed. Here, the flaming wreckage around a car packed with a quarter ton of plastique; there, the stilled body of some leader cut down by an assassination squad. I am there, he would think. He would stare with sated hunger at blood sprays on walls, at churning smoke, at fragments of devastated buildings. Where others saw misery, he saw poetry. Where they mourned senselessness, he recognized the fractal chaos of inevitability.

All things tend toward entropy.

His prayer: Let them burn and let them bleed, but most of all, let them go their way.

Had he believed in the divine at all, Valentine could surely have seen himself as its instrument; but he did not. He was but a man of his world and his times — to an extent a self-made man, but augmented, he came to understand, by deviant biology.

A decade ago, while in his mid-thirties, he had survived another facet of the world's patterned chaos. A malignant tumor had taken root in his scrotum and claimed both testicles before being excised. In the years to follow, while cancer stayed a vanquished foe, the obsessions it had inspired remained. Patrick Valentine could not get enough medical magazines written for the serious layman. Disease was fascinating. Disease was systemic failure that broke down the status quo.

Four years ago he had come across an article on misbegotten chromosomes and their exploitation in the sentencing hearing subsequent to a murder conviction in Texas. The name of Mark Alan Nance sparked dim recollection — a robbery and shooting spree, three days of outlawry in and around Houston. He'd had his fifteen minutes of infamy, then been forgotten by all but those involved.

Don't sentence my client to death, the defense attorney was arguing, because he could be genetically predisposed to commit the crimes for which he's been found guilty. Several months before his rampage, Mark Alan Nance and his wife had been genetically tested to determine why they had conceived a child with severe birth defects, a child that had eventually died. While the abnormalities had been traced to the maternal bloodline, Mark Alan Nance had exhibited an unrelated deformity never suspected, not even known of until two years prior.

It was the first time Valentine had ever heard of Helverson's syndrome.

The article cited comparisons between the defense attorney's wrangling and trials conducted in the late sixties in which reduced sentences were requested for convicted murderers who had double-Y genotypes. Nance's attorney must have done his homework well. Many of the arguments were the same as those of twenty years before. Unhappy case studies of the scant handful of known Helverson's subjects were introduced as evidence.

But in the end, the Texas courts were unforgiving. Death row for Mark Alan Nance.

The arguments in mercy's favor and the portrayal of Nance's miserable life — social malcontent, uncontrolled rages, emotional cripple — rang enough common chords that Valentine began to feel a strange kinship with the convict, loser though the man may be. Above all, though, he had been riveted by the single jailhouse photo accompanying the article.

He looks exactly like I did at his age.

The article had mentioned a certain physical similarity among Helverson's progeny.

It was enough to drive Valentine to a private investigator, paying him well to compile data on the top researchers at MacNealy Biotech, the site of Helverson's original discovery and the primary data bank for its subsequent research. Most looked far too clean to even consider approaching with the kind of offer he was planning. Among them, surely at least one would possess less than bedrock ethical foundations … but which to choose? One wrong selection and he might never get another.

One of the scientists, however, had a skeleton in an old closet. Stanley Wyzkall had been fined several years before for tax evasion. God bless greed.

Valentine flew to Boston, where he arranged to meet with a perplexed Dr. Wyzkall, and paved his proposal with an endowment of $50,000. Ample rewards for information, for progress and understanding — what could be more noble? Discretion would be assured as well as demanded, particularly for Valentine's own genetic karyotype…

Which confirmed his every suspicion about himself.

Ironic. He had become the oldest identified Helverson's syndrome carrier — the first of a kind, possibly — and remained entirely off-record. Only after their deal was clinched did he stress to Wyzkall just how deep was his need for continued privacy.

"We'll get along beautifully as long as we stick to the simple guidelines I suggested," Valentine told him one day over lunch. "We'll both profit immeasurably." Then from a pocket he removed five pictures and dealt them across the table like a poker hand: Wyzkall himself, then wife, daughter, daughter, son. "But if you ever expose me? Stanley? I'll leave every single hair on your head untouched, but I'll center these other four heads in the crosshairs of a scope on a rifle so powerful there won't even be teeth left."

Valentine slid Wyzkall's own photo over to him, gathered the rest, and returned them to the pocket — patting them — over his heart. The man was speechless, but he had not paled. Admirable.

"Have you read Nietzsche?" Valentine then asked.

"No," Wyzkall murmured.

"He wrote, 'The great epochs of our life come when we gain the courage to rechristen our evil as what is best in us.'" With a frank and humorless smile, "Have courage, Stanley. And enjoy my money as much as I'm going to enjoy learning."

Dealing with the devil was the way Stanley Wyzkall chose to regard it, but Valentine took no offense.

And within two months, the devil decided to move his home and entire operation to the Boston area.

*

He drove back across the river and was home in Charlestown before the afternoon traffic thickened to its worst.

Valentine settled into his Cape Cod, secured it, checked every room and closet, made sure each room's pistol was where he normally kept it. Once he could breathe again, he eased into the armchair in the living room and did not leave it until he had gone through Clay Palmer's file from beginning to end. He read slowly, carefully, each word not so much comprehended as digested.

Another one to hope for, another in which to invest his dreams of a surrogate guardian. This one, Clay Palmer, would have the attentions of a therapist in these days of self-discovery, but what did doctors really understand? They sought the concrete and quantifiable becaus

e as long as they could measure something, it was the easiest way to chart progress. To underlying meanings they gave as little thought as they could get away with.

Clay Palmer would in many respects be the last to know what was important. Left to doctors, he would be told only as much as they thought prudent to let him know, as if it were a privilege and not his right.

Unacceptable.

Late in the night, Valentine repackaged Clay's file and took it into his bedroom, pulled back the rug in the center of the floor. Very solid floors in this house, teak, like the decks of old sailing ships. It made a solid anchor for the floor safe concealed beneath the rug and a removable panel.

He opened the safe and stowed the file, along with the dozen others he'd purchased. There they would spend the night until he awoke the next morning, refreshed, and could retrieve them for some selected photocopying.

When he would find time to make it to the post office was anyone's guess.

Sixteen

Adrienne only had to spend one night alone in the condo. A month's lease signed, renewable, she had moved in on Friday, and it seemed wrong, all wrong. The task had taken barely an hour. It looked like a home, but that was all. She spent the rest of Friday roaming rooms that had been furnished by someone else, a stranger, and trying to make herself comfortable on furniture that she had not bought. This was like wearing someone else's old jeans and trying to convince herself they fit just as well. She stood at windows overlooking the neighborhood — hedges and lawns and trees — and they looked lifeless. Three years in the desert and she had forgotten the desolate grip of early winter.

Come on, this too shall pass. This is where I live now.

Sarah arrived mid-afternoon on Saturday, having spread the journey over two days. Adrienne was outside to meet her almost as soon as she had stepped from the car, hugged her tightly and they kissed, and Adrienne wanted nothing more than to spend a few hours getting reacquainting with Sarah's wonderfully distracting body. It was under there somewhere, beneath all those clothes.

"I think somebody missed me," she said.

Adrienne squeezed her hand. "Don't let it go to your head."

And the crisp air smelled sweeter, felt for the first time invigorating rather than forbidding, while the sun strained more persistently behind its prison of clouds. The day had gone from vinegar to wine.

"Do you want the grand tour first," said Adrienne, "or are you itching to lug boxes already?"

"Show me, show me." Sarah fell in step beside her, toward the enclosed stairway to the second floor. "I dressed for the state, do I look like I belong here?"

Sarah tramped up the stairs in jeans and soft leather moccasin boots, a heavy knit sweater, and a down vest. She looked as if she'd just stepped from an ad for a ski lodge.

"Everybody's a chameleon," Adrienne told her.

After seeing the condo, Sarah granted approval, adding only that as long as someone else was picking up the tab, why not have gone for someplace with a hot tub as well?

They put off unloading the car until it seemed indecent. Sarah could never travel as lightly as Adrienne; always something she might want, might miss, might long to hold to remind her of another place or time. She packed keepsakes the way alcoholics packed bottles, always in reserve if needed.

Flashbacks came while carrying boxes from the car, a pleasant déjà vu of two years ago when the commitment had finally been made between them, the house in Tempe chosen, Adrienne acknowledging, This is no passing fling, I love her, this is serious. Friends had shown up that weekend to pitch in, those whom she had gotten to know and love through Sarah. Lesbian couples, mostly, who seemed to form their own extended family, and around whom Adrienne had at first been terribly insecure. Worrying, Will they even accept me? I'm a half-breed. They had, and it really came through that day. Everyone had toted crates and boxes and furniture, had made seats for themselves amid the half-finished jumble. Passing pizza and beer, they traded tales of old moves, horror stories of demolished possessions and runaway trucks and wrecked appliances and fires, those ruinous events that seem to grow more fondly hilarious the longer ago they happened. Adrienne found out that day why it is always wise to withhold the beer until the job is completed. It was the first day since leaving San Francisco that she had genuinely felt this new town to be her home, that her soul had taken root and found a sense of community.

Alone this time, just the two of them to share the burdens, though they were few, and she found herself missing the gathering of a tribe.

When they had everything in, Sarah ran for the door one last time. "Back in ten minutes, I swear," then she dashed off. Adrienne heard the car gunning back onto the street.

She began unpacking, sorting by destination: bedroom, bathroom, kitchen, unknown. One box she opened was labeled, in slapdash marker, Thesis Books. Had Sarah at last decided on a subject she would stick with? Adrienne was on her knees, browsing titles, when Sarah rushed through the doorway with flushed cheeks.

"I couldn't resist." She held up a bottle of wine. "I spotted a package store a few blocks away on Colfax. You want glasses or are you feeling hardcore today?"

"From the bottle's good," Adrienne murmured, still sorting among the books. This was odd. Given the half dozen or so topics Sarah had been flirting with, none of these books seemed to apply.

"Oh," Sarah said. "You found them."

"I gather you finally committed to something … but what are these?" Adrienne then dug out Erich Fromm's The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, Carl Jung's The Undiscovered Self. "There are some of mine in here."

Sarah had the bottle uncorked and headed out of the kitchen, taking the first pull. "You don't mind, do you?"

"Of course not," accepting the bottle to make the christening of the temporary new home official. She handed it back and went randomly diving for more. "Apocalypse Culture … The Theory and Practice of Apathy … Tried as Adults … Generation X, even? What did you finally decide on?"

Sarah sank down to the floor, opposite Adrienne, over the box. "You won't get mad, will you?"

"No…" Saying it automatically, hating that prefacing question; she always had. It was like waving a red flag: You're going to hate this.

Why were you having an affair, Neal?

Well, you won't get mad, will you?

"The idea started taking shape a week ago," Sarah began, "right after you left with Clay. And then when we talked on Tuesday after you'd spent the night before with his friends, that only firmed it up more."

Adrienne sat motionless, not liking the way this was heading. Clay, the friends he wouldn't even refer to as friends … this was too close.

"Don't look at me that way." Sarah leaned forward, elbows propped on the spines of books. "I want to do my thesis on the social climate and milieu that Clay and the others come out of. That kind of doomsday subculture and malaise that are woven through the post-boomer generation. All those people who missed out on the banquet, and mostly got stuck with the leftovers and the bills. The ones who don't have any hope or faith left, to the extent that they don't even see the point of trying."

Adrienne shook her head. "You're doing it again." Hoping to argue on the side of generalities rather than specifics. "Another idea rears it head, and you just can't get enough of it. Do you know how many times I've listened to this same kind of pitch?"

"What, are you keeping score?"

"Six times, Sarah."

"So I've finally committed myself to one. You knew it had to happen eventually. This is what I want to do. This is the one."

"And I've heard that line, too." She snatched the bottle away and belted down a swallow, flipped the silky blond hair up off her neck; it suddenly felt too hot. "And I suppose if you stumble across some lost tribe up in the Rockies, then that'll be the one, the one, the big one."

"Objection!" Sarah cut in. "Ludicrous example." And Adrienne nodded, Oh, all right, so it is, I speak in principle but have it your way.

Sarah took the bottle f

rom her and set it aside so she could hold her by both hands. "I told you I wanted to do something I could get really passionate about. And I think this matters very much. Besides," she said, squeezing Adrienne's hands, "my adviser liked it."

She felt some of the starch flow from her shoulders. Well. Well. This did shed a light of validation on things, didn't it?

"Cultural anthropology?" she said softly. "Fishbine thought this idea fit?"

Sarah nodded. "He's actually pretty progressive." She let go of Adrienne's hands and implored with her own as she rocked up onto her haunches. "I think the next time the world yields up another lost tribe, that'll be it. There won't be any more. We've found them all and most of the time they've become a little more like us, and they're never any better for it. And you know? That's what intrigues me most, why we're the ones so screwed up.

"There's nothing I could do with a more primitive culture that wouldn't be redundant. So why not look at my own the way it is right now? The whole field of anthropology, it's been at a kind of pivotal point for the past several years. It's still asking the same questions, but we have to ask them in a whole new context. So in a way, the whole field becomes fresh all over again."

"Because the world's changed so much," Adrienne said.

"That's right. It's taking a new look at family structures, gender and race relations. Migration. Warfare. Law and order. All of those things are giving us fits right now and it's because we mostly ignored them, except in the most superficial ways." Sarah ran both hands back through her hair and it became a savage mane. "I just want to be part of that. It excites me."

"I know," said Adrienne. "I understand that. But…" And why such a prickly reception to this? She knew perfectly well that Sarah had not come up here to intellectually seduce Clay from her, but to be just as perfectly irrational, that was exactly how it felt. And she almost had to laugh. Fighting over a man? That was the last thing she'd ever expected to happen.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

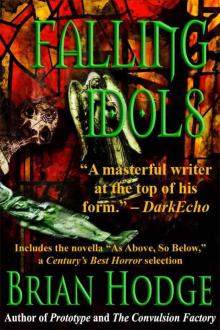

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols