- Home

- Brian Hodge

Prototype Page 4

Prototype Read online

Page 4

Was she sufficiently distanced from intimacy with men that now they had assumed the fascinating aura of creatures to be studied? Perhaps so. Live in a rain forest, and you take it for granted; live in a city, and that forest exudes a powerful allure to the explorer of terra incognita.

And for some explorers, there is no territory so enticing as that which can kill them.

Adrienne checked the time. A quarter past four. On duty and she didn't even know it. She picked up her phone and buzzed down to Ward Five.

"This is Dr. Rand," she said. "Could you have an orderly bring Clay Palmer up for his session?"

*

When Clay arrived, Adrienne almost had second thoughts about turning down the orderly's offer to linger behind; in his eyes was the implicit end of the offer — just in case, you know. It would have sent a poor signal, though. She wanted Clay to trust her? She had to trust him.

He looked drawn, tired, but reasonably well. Good color beneath his fading sunburn and nicks and bruises. He had been recently shaved, so most of that scruffy drifter quality had been sacrificed to the razor. The casts made the visible portion of his arms appear deceptively thin, the lean, ropy arms of a gangly teenager. His eyes flicked about the room, taking in decor here, books there, the layout in general. Cataloging, almost. She had met veterans of recent wars and skirmishes who did much the same: came into a room evaluating it for weapons and for cover. She briefly wondered if a military stint in his background had been overlooked, then decided no. He'd had no time, not with that file she'd just read.

"Where do you want me?" he asked.

She gestured. "Whichever you prefer. I just want you to be comfortable."

He chose the couch over either of the two plush chairs set before it, but would not recline; sitting, instead, with his back to the wall while she took a chair. She eased into the session with small talk — how are you feeling, fine, how are your hands, fine — the little opening moments that could either be a cautious dance or a subtle sparring match.

She asked if he would mind if she recorded their conversation, and he said no. From her desk she took a small Sony, about half the size of a paperback book, and placed it on a table adjacent to them, set it rolling. She never understood counselors who used voice-activated recorders; even the duration of a pause could sometimes be more telling than words.

"This is the part where we start talking about my sex life and toilet training, isn't it?" His streamlined face was half-turned her way, his eyebrows mock-inquisitive arches.

"Only if they seem relevant."

"I'd say they are. These casts?" He lifted them, ponderous weights from which mere fingertips protruded. "I can barely aim myself steady enough to hit the toilet." A self-effacing little grin of embarrassment, but something about it rang hollow. "And I definitely can't whack off. Can I count on a little relief from you?"

"The last time I checked, that's not in my job description," she said. At times such as this she wished she wore glasses; nobody looks more like they mean serious business than someone tugging off glasses with one hand. She continued, voice even-tempered and professional: "A remark like that is way out of line and we both know you're aware of that. Dirty little propositions quit shocking me a long time ago, so if it's all the same to you, I'd rather get past that phase of your evaluation of me. Good enough?"

He did nothing for several moments, then grinned lazily down toward the couch with a single conciliatory nod. Whatever test that had been, it appeared that she'd passed.

So proceed.

"Neither of us brought this up on Friday morning, when we first spoke, but there's something I'm still wondering about. Not that it's necessarily important — more for my own curiosity. What brought you down this way from Denver?"

"I just wanted to get away by myself for a while."

"You wanted to be completely alone, then." More a statement of clarification than a question. You had to be careful with direct questions; too many and a session could turn into an interview that yielded facts, but ignored the richer vein of feelings.

"I wanted to get away from everything I was familiar with. So about a week and a half ago, I just left. You know how you go for a walk to think, to clear your head."

"If you wanted to be alone, you could have locked your door and not answered it, and unplugged your phone."

He cleared his throat, uncertainty shifting across his face. "I knew that wasn't going to be enough. Sometimes that is enough, it works … but it's a very passive way of going about it. Sometimes you need that distance. It didn't even seem right to drive it. So I didn't."

Adrienne eased forward in her chair. "Eight hundred miles is quite a walk to do some thinking."

"I had a lot to think about."

"And what was that?"

"Besides, I was hitchhiking some of the time. The way I see it, that's not cheating, that's allowed."

She said nothing — let the silence weigh upon him until he decided to do something about it. Her question hung there and he was perfectly aware of it; she could tell in a flicker of eye contact. What she could not yet discern was if his evasion was genuine, or one more little game.

Clay slid forward on the couch. The hospital robe bunched beneath his legs and he stood. Wandered across the office to stand before her print of Metcalf's The White Veil while she looked at his back, framed against the tranquil snowscape.

"Impressionism, right?"

"Yes."

"French or American?"

"American."

He nodded, still presenting his back to her. "I know this guy who's an artist. His work … it's nothing like this. He doesn't see the world this way."

"Is this a friend of yours?"

Slowly, Clay turned his back on the scene and returned to the couch. She decided his evasion, as well as his lengthy contemplation, were genuine.

"Friend is an outmoded concept, isn't it? Graham … I get along with him, I wish him well, I like his work. We … we protect each other in a way. But I wouldn't even think of dying for him, so I don't think I'd make a very good candidate for friend, no."

Adrienne nodded. She could tell, for the time being at least, that the way to Clay's psyche was going to be a serpentine path. He did not seem to mind ruminating philosophically about matters, but dealing bluntly with his own feelings was a thornier task. She'd have to start out reading him mostly by his reactions to things. Pick away here and there and see what flaked away, like rust.

"Why don't you describe Graham's work to me. The things you like about the way he sees the world."

Clay shut his eyes a moment, moved as if to run one hand through his hair, then stopped. Her breath caught in her throat for an instant. A concussion, that's all he needed right now.

"His work doesn't present the world like that," waving one cast toward The White Veil. "Fuzzy, soft focus … diffused. Even though that's a winter scene, it's still warm. Why do you have it hanging there, anyway? That world's dead. Is this supposed to be some kind of memorial?"

She frowned. "'That world's dead' — I don't quite understand what you mean by that."

"Artistically, I mean. Been there, done that. Let's look at something relevant." Perhaps she was on the right track — Clay was starting to appear rather captivated. "Who honestly needs a snowy hillside anymore? It means nothing in terms of anyone's life. Maybe it meant something when it was painted, but now it's completely devoid of relevance."

"Some would say beauty exists for its own sake, regardless of its time."

"But most of the time it doesn't mean anything. It's like Marx's take on religion: an opiate. It's a false pat on the head to tell you not to worry, everything's fine."

"So, what you're saying about Graham's work is that it reflects, say, a harsher truth that you find to be more real."

"Right." He nodded. "Right. It's not metalwork, but a lot of it looks that way. Even though he uses oils, mostly, oils and acrylics. Looks very metallic. His paintings, they're ugly as hell, but it's th

at bizarre kind of ugly where you can look at it and find a perverse beauty, know what I mean? They look filthy, most of them. Not pure and clean like that." He spared another long look at The White Veil, then seemed to dismiss it with a shake of his head. "I don't mean filthy in a pornographic sense. I mean the way metal looks before … I don't know … before it rolls through a Detroit factory and gets shaped and smoothed out and painted and waxed. Raw metal."

Her eyes narrowed as she tried to summon a composite of the feelings such paintings must evoke. Something about them conjured a cold and harsh sense of brutality. "What kind of imagery in them do you recall?"

"Oh … gears. Girders. Smokestacks. Twisted bridges that don't go anywhere. Piles of scrap iron." Clay bit into one corner of his mouth. "Graham calls them post-industrial landscapes. His studio and apartment, all those paintings around … he once called it the junkyard of the world."

"And this is a world of … what?" She was curious. Decay? Progress in rampant decline? Fill in the blank.

He thought for a moment. "A world of barriers. I mean, what's metal for, if not keeping things in their places?"

Adrienne recalled the condition of Clay's clothing the other night, when he had been brought in. The boots caked with dust, both inside and out, the dusty jeans and jacket and shirt. With mild dehydration and sunburn on top of it all. The obvious conclusion was that he was not long out of the open desert.

"That world reflected in Graham's paintings," said Adrienne, like the sliding of a gentle probe. "Is that the world you wanted to get away from for a while?"

He didn't answer, not for a minute, maybe more. One never realized how much time was compressed into one minute until hearing it tick away, waiting for a reply in a dead-silent room. She took care to watch his face for the emotions it betrayed, and clearly he was wrestling with those barely understood compulsions that drove him.

"I guess it was," he finally admitted, as if it were some sort of moral defeat. "But everybody needs that, sometimes, so I don't know how much you can read into it."

Enough, she thought. In this society the call of the wild was rarely answered in much less than a Winnebago. Or at least with a backpack and four-wheel drive. Clay's had been a much more primal response.

"This need must have been considerably stronger in you than in most people, wouldn't you say?"

"Probably." He shrugged, apparently unconcerned with pursuing a comparison. "I was on the road, hitching and walking, close to a week. The desert? I guess I came into Tempe about three days after I got off the road completely, but I didn't want to stay long, I still wanted to keep going." He wet his lips. "Do you know what it's like to walk for three days and not see asphalt?"

Adrienne shook her head. "No, I don't, really. Maybe you could fill me in."

Clay tilted his head back, gazing at the ceiling, through it. "Something gets stripped away. It's hard to say what it is, exactly, but it leaves you. And you're not sorry to see it go. The only things you hear are things that have already been making noise for a few million years. You regress … part of you hits this embryonic state. It's easier to pick yourself apart this way. To look inside and do some serious thinking. That's what it's like."

"If you went out there to do some soul-searching," she said, "were you able to walk away with any conclusions?"

"One big one, for sure: Jesus must have gotten really hungry after forty days."

Okay, she deserved that. She knew better than to ply him with such a direct question. One observation, though: Whatever the trip had represented to him, likely it had been a failure.

And his choice of mythic analogy was interesting, on second thought. Maybe she could work with this after all.

"Jesus went into the wilderness to confront — and ultimately overcome — a devil. In very loose terms, do you think it's possible you were doing the same thing?"

He rolled his eyes. "I don't have a messiah complex and I don't have delusions of grandeur."

Adrienne nodded, conceding. "But you do have a sense of the mythic. Friday morning? 'Clay Palmer … of the Gehenna Palmers'? You may have been joking, just as you said, and then again you may have been telling me in a very subtle way that your earlier family life was hell. Either way, the mythic element is there." The Jungian disciple in her, browsing the storehouse of the collective unconscious: those basic elements and symbols that resonated in humankind the world over, regardless of culture. "You don't need a messiah complex or delusions of grandeur to relate to a story about a journey of confrontation and self-discovery. Or to go on one."

Eight hundred miles he'd come, but clearly he had been more concerned with seeking a goal, rather than running from something behind him.

"Was that what this trip was all about?" she asked. "Your own journey of self-discovery?"

Clay Palmer may have been a stranger, but as she watched him honestly try to wrestle with this one, she realized that some evasive shadow in both their souls was quite similar. How well she understood that mysterious lure of the desert, its siren song of hot gusts and desolate winds, chilly nights, and the harsh, unforgiving fact of its very existence. It had pulled her away from the city of her birth at a time when her entire life had been in flux.

And while she couldn't see it from her bedroom window, she at least knew it was there.

Her transition had been made, of course, via all the socially acceptable routes. New job, new house, new friends, and, if a bit less orthodox, a new love. Clay, however, had stripped away all such niceties until only an elemental core remained. And what was this inside her — an amusing twinge of jealousy over the purity in his method?

"Confront this, Adrienne," he finally said. "I don't fit into the world, and it took a long time, and it still isn't easy, but I finally started trying to accept that. Fine. But that doesn't mean I don't think somebody or something, somewhere, still owes me a damn good explanation."

Four

Days passed, bones began to knit…

And itch. In years gone by there had been summers in which he had lain naked and brooding on forest floors, or near the shores of lakes, and as he invariably would have forgotten mosquito repellent, they would come near to consuming him alive. They would leave him covered with a raw quilt of bites that he would scratch until blood welled and he was left almost mad with the screaming constancy of sensation.

The itch of skin, the itch of bone. Between the two, he preferred the former; the latter was agonizingly more than skin deep. Would that he had the ability to turn inside-out, or plunge a hand deep within, and scrape along every hidden channel that plagued him.

But he would get through it. No one could itch forever.

Of the pills prescribed to stabilize his expected mood swings, Clay wondered if they didn't work more by power of suggestion than by anything else. Perhaps he was just on a natural remission as far as those tendencies were concerned. There were no threats here; more than anything, he was surrounded by a routine that stultified by its blandness, boredom. But if slipping pills down his gullet in daily rations made them feel safe, fine. He knew better. If he had to kick, or bite, or swing those casts like weighty gauntlets, he knew he could, without hesitation.

And what would Dr. Adrienne Rand say then?

It would be a blow to her, all the time she'd put in on him thus far. Given past experience with the prior skull dabblers who had shown him to their couches, the burden of proof that she wasn't just going through more motions was definitely on her shoulders. And she had held up all right. He knew the difference by now. Familiarity had bred a general contempt for most of her ilk, but for now he was willing to grant that she had a genuine core of human interest. "Help me, Adrienne," he could cry, like a child awakening in the night, and she would come running.

Not that she was free of self-indulgent curiosity. This too he could spot when she posed questions, or lit up with fascination at some minor revelation he thought insignificant. She had an agenda as mercenary as it was irrelevant to him, but as long as

she kept humanity in the foreground he would not begrudge her the rest.

"You'll win some shrink, somewhere, the research grant of a lifetime," Uncle Twitch had told him last year, mostly joking but not entirely, and it had been one of those rare occasions when Graham had actually laughed.

Right out of the psychoanalytical starting gate, Adrienne put him on twice-weekly sessions, Sundays and Wednesdays, and would periodically pop by for brief visits. Spot-checks?

As faces went, he supposed hers was the only one he looked forward to seeing in the hospital; the rest were drones and human dross. Adrienne Rand, though, brought with her this pinched look of interest, as if his room wasn’t just one more stop along the hall. He appreciated that she never exuded patently false cheer. For what it was worth, perhaps she was of more inherent honor than most who wore the Homo sapiens designer tag.

She was tall, only an inch or so under his own five-nine, and with her blond hair pulled back, and the seriousness with which she took his case, it soon became entertaining sport to fantasize her into roles he doubted he would ever tell her about. He saw her in black Nazi leathers and crimson lipstick, a Goddess of Pain and Humiliation who ruled the halls of an unspeakable clinic unknown to the medical mainstream. She would carry a riding crop for effect, and an ominous black bag filled with painful instruments of exploration. A well-greased glove might slide down his throat as she sought to tear out his heart, or up his rectum in search of secrets dirtier still. It might very well be the only thing before which he would have to lie helpless…

Just idle thoughts. Everyone needed diversions while on the mend.

In truth, she gave him no encouragement that such fetishes were part of whatever twisted upbringing she would call her own, so he settled for satisfying her endless curiosity about his past.

He told stories, random synaptic firings with no apparent pattern, and he noticed that the more he remembered, the less Adrienne spoke. She did not have to; she was sucking it out of him with her eyes and her presence alone.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

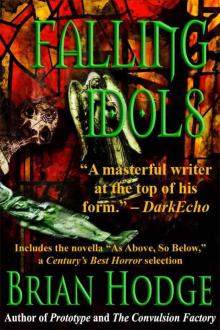

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols