- Home

- Brian Hodge

Prototype Page 5

Prototype Read online

Page 5

So here it is, Dr. Adrienne Rand. Surely you've heard whining tales of misfits before, but if it means that much to you:

Doesn't everybody have parents who go through life looking at each other as if they both have made a horribly wrong turn somewhere in the distant past, but cannot recall precisely where? Probably it is easier, in the day-to-day, to pretend it never happened than to do something about it. One can fall for years before striking bottom, and it doesn't take nearly the effort of one minute of climbing.

Doesn't everybody have a father who was nearly forty by the time he got around to siring offspring? A father who proudly fought with the Marines in Korea and let no one forget it, and who saw his firstborn as a prospective little soldier to be marched around and around within the house on peculiar drills? Three hours is forever when you're five. Left, right, left, right, and don't you dare cry, you little pussy, if you cry I'll smack you and your mother, and you'll watch. He learned to toe the line, and by the time he was old enough to understand the omnipresent television show called Vietnam, and listen to his father's armchair Pentagon rhetoric about everything that was being mishandled there, young Clay's big fear in life was that it would all end before he was old enough to ship over.

Doesn't every father hold his kid's hand over the gas-stove burner, an exercise in discipline?

Doesn't everybody have a mother whose eyes deaden with every increase in breast droop and hip expansion, and to whom vodka is a wretched god that gives and takes away? A mother who, too often, cries herself to sleep on a sagging couch and clutches her child to her heart and, with reeking breath, murmurs promises of tomorrow? We'll go away, for the rest of our lives, but remember, you can't tell Daddy, it's our own special secret.

Doesn't everybody have brothers and sisters who failed to survive? He was first, the eldest, therefore the strongest. His survival seemed perfectly natural at the time, as one crib death and then three miscarriages claimed all others who might be called siblings. He recollected his small, solitary celebrations with root beer and a hidden cache of firecrackers, because he had outlived yet another.

How insular, this world of childhood, when anything might be perceived as the norm.

"How old were you when your sister died?" Adrienne asked, a Wednesday afternoon in her office. He actually looked forward to the sessions more and more. They were the two hours per week when he felt farthest from his itching bones.

"I was five," he said. "It's one of my first real memories. I can't say for sure, but something about that day had a real Sunday-afternoon feel to it. I think we'd been to church … and I remember a roast smell, all through the house. Beef roast, that was always Sunday food. Special. Family day, you know. All God's children love a good roast."

He looked at Adrienne in her chair, legs crossed at the knee, where her interlocked fingers rested. All she did was nod, but he knew her nods by now, could differentiate among them. Yes, she was saying, go on, tell me more. Feed me.

"I remember my mother, her voice at first, coming out of the nursery and down the hall. High, very high, and loud. Like she was trying to talk, but something was clipping frequencies from her voice, so it was just this … this sound … this creepy sound. Crying, but uglier, just … nonsensical. Like the sound of chaos, if chaos could grieve. I'd never heard anything like that before. It scared the hell out of me. I just stayed put on the dining room floor — I was playing with a toy truck — but even though I was scared, what I really wanted to do was run down the hall and see why she was making that noise. Because whatever it was, if I saw it and I didn't scream, I knew I'd see something I'd never seen before. I didn't know what … maybe like a god suddenly showed up in there or something. It was Sunday, remember."

"Was this the first time your parents were forced to explain death to you?"

Clay nodded. Memories were like dominoes, one tripping another tripping another, until all lay flat and inert. "My father sat me down on the back stoop with him that evening. The sun was going down. One of the neighbors was grilling steaks, must have been. That smell of meat again." He shook his head. "The backyard seemed bigger at twilight. It always scared me then, I thought it was changing on me. I couldn't trust it, it wasn't the same place I'd play during the day. I, umm … I guess I must have asked where they'd taken Amy. It was the only time I can remember seeing him cry. Actual tears on that leathery, pitted face — it seemed so wrong. He told me God sent some people to take Amy away, because He needed more angels." Clay laughed. "I think that was the extent of my father's theological understanding. And if he thought he was giving me comfort, he couldn't have been more wrong. I sat there wondering, if it was that easy, what was to stop them from coming for me the next time?

"'At ease,' he told me. He actually said that, 'At ease.' And then he nodded and told me, just this once, it was okay to cry if I wanted to. I sat there and tried, but nothing happened, so I told him I'd save it for later. He put his arm around me and said he was proud of me for that."

"For staying strong, you mean."

"Not so much strong, as in control. Control, that was a very big issue for my father." He supposed it still was. He had neither seen nor spoken to nor corresponded with either parent since leaving Minnesota four years ago. His father would be sixty-four now; there was no reason to believe him dead. Men like that never died before living a full lifespan and more, inflicting their share of misery on the world. "Maybe that's what shook him up most about my sister's death. And my mother's round of miscarriages after that. It must have been her drinking that did those. She was probably so toxic inside, nothing could live for very long. He used to hit her but she wouldn't stop. Everything was way the hell out of his control. Maybe that's what first taught me that something could be out of his control. It was … liberating. So I became the miscarriage that lived."

It was his fourth session with Adrienne when that came out, and shouldn't he be feeling at least some relief from such confessions? One would think so. These rancid old memories, he'd not called them up for longer than he could remember. They were episodes in the life of a Clay Palmer he no longer recognized, a family that wasn't truly his. The most he felt during it all was some minor uneasiness now and then, never any real pain.

Quite the contrary: There could be fun in this, as if he were a boy, with a boy's usual fascination with morbidity, and he had found a bloated roadside carcass to prod and turn over, and whose distended cavities he might examine to see what squirmed inside.

There was no real pain linked with telling Adrienne of the child he had been, the slings and arrows withstood. Doesn't everybody know small boys, late to grow, last to be chosen, first to be punched and spat upon when childhood begins its rites of stratification? Some boys simply grow up magnets for fists and spittle, some subtle thing indefinably strange about them. Such tormented boys radiate their otherness from every pore and cell, a phenomenon everyone recognizes but none can qualify. It might as well be debated why the sun rises in the east.

Yet why such variance in their adult selves, when all have been much the same victims? Some grow stunted, some straight and true, while others grow like lone pine trees on the sides of barren mountains, twisted by winds into ghastly shapes that are freaks of nature, one of a kind, fundamentally abhorrent.

Were these the boys who learned to bite in self-defense? Who smiled, bully-blood on their lips and chins, at bigger boys who for the first time knew pain and tears and their own high-pitched shrieks? Were these the boys who, no longer tormented, were shunned instead, abandoned to sit alone on green playgrounds with their sack lunch or a book or their own thoughts, the object of sullen loathing and — admit it — fear?

In his experience, in his humble estimation, they were.

For doesn't everybody stumble across their own survival mechanisms deep within, as if inscribed upon tablets that cannot be read, yet are nevertheless comprehensible? The most ancient languages are learned by instinct.

This was his world, the one into which he ha

d been born, the world that had penned its inarguable natural laws upon his heart, then demanded obedience or death.

How odd, then, that his fellow citizens had passed so many laws against what seemed to come most naturally.

But maybe it was him, all him, all wrong. At times he fretted about his heredity, some hideous genetic mistake inside, as had once been attributed to mass-murderer Richard Speck. Adrienne told him he need not worry, such claims had been mostly sensationalism. It was more vital that he focus on what he could control, could understand.

And it came about fifty minutes into this, his fourth session in her office. Two full minutes of silence passed before he fell back into his present self from the past, and realized his broken bones did not itch. They would later, surely they would, but for now it was like realizing there was an end to the routine that had so quietly engulfed him.

He would be discharged soon, would be on his way. Back to Denver, yes … but where?

This was solitude; this was the loneliness spoken of by hermits isolated within crowds. This was the desolation that old Eskimos must feel when sitting on the ice, abandoned by family and waiting to die.

Clay's breath began to come in spastic hitches; his throat constricted and felt suddenly raw. Worst of all was the scalding presence of tears before he even knew they were on their way. It was a low and brutish thing to do, but he could not stop himself. His body, loathsome thing that it was, was betraying him for reasons of its own. He was clueless, and spilling forth from within.

"Shit. I don't — don't understand this," he choked out. How grotesque his voice was.

Adrienne was there for him, as much as she could be, leaning forward to press a tissue to his fingertips. He looked at it for a moment before letting it flutter to the floor. If he was going to cry, then let it soak him.

His sudden perspective on the office was that of a vandal. So much to break, so much to shatter into fragments that would cascade with enough noise to drown out tears. What release destruction could bring. He felt the urge resonate in bone and fiber, nerve and cell. It crawled within his arms, trembled within his legs; it wrapped around his heart and sang inside his blood.

He clenched shut his eyes, wrapped himself with both arms, until it passed as surely as a seizure.

He looked at Adrienne and realized she knew. She read it all in his face and her fleeting wisp of fear was as palpable as a scent. She had placed her faith in lithium and it had failed her, whereas his resolve had triumphed…

If only this once.

"Help me," he whispered.

And this, too, might happen but once.

Five

By sunset, everyone at the party had finished eating and now tended to amiably drift from one conversation to another. Adrienne found herself at the edge of the rear deck with Sarah, seated, content to watch the multihued glory of the melting sun. The back of Jayne and Sandra's house had a western exposure that opened onto a desert panorama, an ascetic flatland where spilled the day's blood, rich and rubied.

It was the kind of house, kind of location, that she would have preferred, had Sarah not hungered to remain closer to the heart of Tempe and the campus. She could look at this sight every evening, never tiring of it, for it would never be the same twice. This realization pricked her heart with a tiny stab of loss: How many sunsets had she missed already in her life that she could never retrieve?

Sarah propped her feet on the wooden railing; from her lap she took a bowl of apple slices soaking in a splash of white wine, and placed it in Adrienne's lap. "Be my wench. Feed me," Sarah said with a grin, then tipped her head back, opened her mouth expectantly.

"You look like a baby wren," Adrienne said and played along. One cool, crisp slice after another, dripping with wine — she set each on Sarah's tongue and watched them slide past her lips. Drops of wine plinked soft as new rain and began to trickle down Sarah's cheeks. Adrienne leaned in with flickering tongue to kiss them away.

"Are we creating a spectacle?" Sarah asked.

Adrienne looked over her shoulder to the house and sliding glass doors, open now, looked at the small milling groups. No one was paying attention. "Yes," she said anyway.

Sarah half-groaned, half-laughed. "Good." She returned the kiss with sticky, sweetened lips. "I knew I could turn you into an exhibitionist if I had enough time."

Years before, when married, Adrienne would watch women who put on such public displays with men, and was usually tempted to suspect them of ulterior motives. Showing off, or using one man's attentions to attract another; something about them seemed terribly self-conscious, like exhibitions of plumage or twitching haunches during mating season.

Now she was willing to accept that such things had been done, at least some of the time, simply for the carnal joy of it, and that she had been jealous of others' freedom to do something in full public view that she herself would never have done. Sarah had been more instrumental than anyone in changing her mind, just by being Sarah. She got like this whenever and wherever the mood struck; in private or not, it never mattered.

They had met after Adrienne had been in Tempe for half a year, and had sat next to each other at an evening guest lecture at the university. Nothing short of broken legs would have kept Adrienne away. The speaker was once a student and protégé of Erich Fromm. Adrienne adored Fromm, whose theoretical stances on social psychology, along with the more mythically oriented stances of Carl Jung, had driven stakes into the heart of much of what she found lacking or simplistic in Freud. Jung and Fromm comprised the two mighty pillars on which she had built her own outlook.

Adrienne had arrived as early as she could and sat third row center in the lecture hall. Two seats over sat a woman who doodled in a notebook and, minutes later, kicked off both shoes and propped her dirty bare feet upon the back of the seat before her. Adrienne could not decide if she was rude or just ill-bred.

And what wide, strong feet they were, too. Adrienne couldn't help but stare, fascinated by the sturdy bone structure, the power in the high arch, the light tracery of veins, then the sudden thought of every place they must have carried this woman throughout her life. She was possessed of an abrupt desire to touch them, stroke them. The woman caught her staring, and Adrienne tried to look away, but too little, too late.

"At my day job," said the dark-haired woman, leaning in, very deadpan, "I tread on grapes."

"Oh." Adrienne was brought up horribly short, never before at such a loss for words. Shouldn't she say something, at least? "I shrink heads."

She'd blurted it out before she realized it, and red could not even begin to describe the color blooming across her cheeks.

The woman smiled, wide and delighted; Adrienne next caught herself staring at her full lower lip, as moist and ripe as some enticing fruit.

"A genuine modern primitive," the woman said, reaching out to shake Adrienne's hand. "I never would have guessed."

The lecture ended as, if not a total loss for Adrienne, then near enough, an hour and forty minutes of concentration shattered. The amplified voice wafted past her like a breeze she was only fitfully aware of, while instead consumed by every aspect of the woman she was to later know as Sarah Lynn McGuire. The sound of her breathing, the etching of her pen across page after page of notebook paper. No movement, from a shift in her chair to a sweeping of hair from her eyes, was too minute to escape notice. Adrienne felt progressively warmer throughout this exercise in torture, bathed in an imagined cloud of pheromones, while the object of a desire she'd not even realized she had was less than three tantalizing feet away.

Now this was going to take some introspection.

She had long acknowledged herself to be bisexual, if latent these days. It had been years since she'd had any kind of sexual relationship with another woman, and even those had been fleeting, sandwiched between lengthier affairs with boyfriends. First had come a handful of tentative high school encounters, more confusing than anything, wherein offbeat flirtation had led to hesitant kisses a

nd experimental touches in the cars or bedrooms of friends, after which she would retreat to the solitude of her own room in the middle class fortress of her parents' home, and sit without moving, aware of the fearful throb between her legs, as insistent as an accusation. It never quite felt wrong enough to frighten her away from a next time.

With college came greater assurance, and the consummation of what had previously been mere sex-play. She possessed her own life there, as did the women she occasionally met who wanted to be more than friends, and they had all the time needed to explore. It was no longer experimentation, this she recognized right away. The light touch of a nipple beneath her fingertips, the grinding undulation of a gently swelling belly against her own, the musky taste of petaled labia and budlike clitoris upon her tongue … she took to these as naturally as she had taken to men and their rougher, more singularly directed passions. Neither seemed to possess a clear advantage over the other. She was either neatly divided into halves, or, conversely, unified into a perfect whole. Omnisexual? It had an intriguing connotation.

Still, there had been no one of like gender in her life since graduate school, and she had come to think of her lack of sexual differentiation in lovers as a phase she'd outgrown. In eighteen months of preliminaries and seven years of marriage, Neal had never even realized she was bi. Although after his philandering and their divorce, she'd thought of sending him a card — Guess what, I like pussy too — but it seemed a childish and spiteful thing to do.

Not to mention no longer applicable.

Or so she had believed, apparently erroneously. Her reinvention of self in Tempe had apparently brought the past. Adrienne credited the desert, naturally. Those winds and infrequent rains, no telling what buried treasures might wink anew in the dawning sun after a night's erosion.

What greater proof did she need? For there she was, trapped in a lecture hall with her sweat and her hunger and a stranger. Going on thirty-two years old and her heart pounding as if fifteen, while she had no way of knowing if the woman seated within her reach shared even a remotely similar orientation.

The Weight of the Dead

The Weight of the Dead Lies & Ugliness

Lies & Ugliness The Convulsion Factory

The Convulsion Factory Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell

Hellboy: On Earth as It Is in Hell Whom the Gods Would Destroy

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Picking the Bones

Picking the Bones Worlds of Hurt

Worlds of Hurt Oasis

Oasis Nightlife

Nightlife The Darker Saints

The Darker Saints Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls

Just Outside Our Windows, Deep Inside Our Walls A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult

A Haunting of Horrors, Volume 2: A Twenty-Book eBook Bundle of Horror and the Occult Dark Advent

Dark Advent Mad Dogs

Mad Dogs Prototype

Prototype Deathgrip

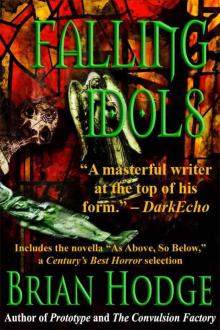

Deathgrip Falling Idols

Falling Idols